by Jenny Rose | Aug 26, 2023 | A Flourishing Woman, The Journey

Two weeks ago my 87-year-old demented mother fell in her memory care unit and broke a hip for the second time in less than a year. Eight days later she died in a hospital under the care of Hospice, my brother at her side.

Until I sat down to write this, I was afraid I had lost my words, lost the need to write them, lost the ability to form them into meaning. But I haven’t. I’m still a writer. This remains. That’s a relief.

Oh, I’ve been writing. Lists. Notes. An obituary. Texts. Updates to family and friends. Daily journaling. But it hasn’t been creative writing. It hasn’t been this blog, or my fiction. These last two weeks have passed by, the first in a blur of pity and anguish, and the second in numb relief glazed with exhaustion, and I have not posted or published. I haven’t kept track of the days; they spill into one another, as the days and nights blended together while my mother lay dying and we waited.

For a time words have simply been inadequate to relieve the pressure of my feelings in any organized or coherent way. They flew away from me, leaving a series of kaleidoscopic impressions, sensual details so vivid they frightened me with their power.

While my mother lay dying I reread my childhood copy of The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Graham. Reading has also largely failed to sustain me during this time. I find myself unable to focus. I read a paragraph or two, and then realize I’ve been sitting staring into space, out the window or into the garden, not hearing, not seeing, not even thinking. Just sitting. But I needed a companion for the night watches, something comforting and familiar. Something innocent.

Photo by Josh Applegate on Unsplash

The fan in my window purred during those hours, blowing in cool night air and an occasional moth or mosquito. Every night, when I go to bed, I light a tea light in a candle lantern. When calls or texts reached me, I knew when I opened my eyes if it was before midnight or after, according to whether the candle still burned. Propped up on pillows, glasses on, my small bedside lamp alight, I spoke to Mom’s facility staff, emergency department doctors and nurses. I texted with my family. I read, the well-remembered illustrations making me smile as I communed with Rat, Mole, Badger, and the ridiculous Toad, finding respite for a few minutes before turning off the light and lying awake in the dark room, listening to the fan, feeling my heart beat, resting, breathing, waiting.

While my mother lay dying and after, I’ve stained wooden pallets. My partner and I are building a 3-bin compost system against the back yard fence. We set out sawhorses. I found an old brush, a rag, a stirring stick. We bought stain. I lay a pallet on the sawhorses, brush away dirt and debris, and paint every surface. The raw wood soaks in the oil-based stain, a rich brown color. The brush is more and more frazzled. I’m sloppier than I would be if painting a wall. The pallets are splintery. Some of the boards are split or loose. I bend over, the sun hot on the back of my neck and my bare arms. Mosquitos bite me. Stain drips between the boards as I brush their edges, dappling the sawhorses, falling onto the filthy old cream-colored jeans I’ve been wearing all summer in the garden, and onto my worn-out sneakers, used only for outdoor work now. As I maneuver between the boards, stain smears the skin of my hands and wrists. I kept the phone close, in a patch of shade.

This is the only sustained work I’ve been able to do. Now and then I wash a few dishes. I’ve done a couple loads of laundry. I go out into the garden, note the trimming, pruning, composting, mowing waiting to be done, and turn away. It all feels like too much. I don’t know where to start. It’s impossible to open the garden shed, get the tools, wheel out the wheelbarrow.

But the pallets. I can do that. It’s a simple task, direct. I don’t need to make any choices. Each side takes fifteen or twenty minutes. When I’ve finished a side, I wrap the brush in an old plastic bag, cover the can loosely, let the pallet dry an hour and a half in the sun. Then I turn it over and begin again. Two coats each side. One side after another.

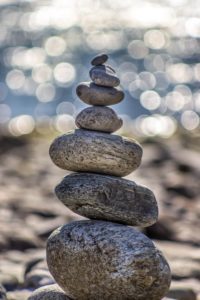

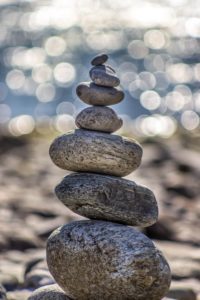

Photo by Manuel Barroso Parejo on Unsplash

The smell of stain. The prickly feeling of intense sun on my skin. I think about compost, recycling, breaking down life to sustain new life. I think of ashes to ashes and dust to dust. I wonder if I’ll ever use the compost bins without thinking of Mom. I wonder who names the colors of stain and paint. I chose ‘Canyon Brown’ for this project. I vaguely hear birds, cars passing by. Small groups of women walk by in clumps, hospital employees on their lunch break, talking about families, gardens, school starting, hospital gossip. I should be at work, on that same campus, just a ten-minute walk away. I should be, but I’m not. I’m here, staining pallets, waiting for Mom to die and then on bereavement leave.

Am I bereaved? How would I know? I wonder why I don’t care enough to follow the thought. I let it drift away.

I decide I want to make bread. I don’t eat bread often, so rarely make it any more. But my rosemary is bushy and ready to be harvested, and someone brought fresh home-grown garlic into work to share before … before all this. So I make a sponge, stirring together milk, a little sugar, yeast, water. I chop fresh rosemary and garlic, very fine. I take flour out of the freezer and let it warm. The dough is heavy under my hands, sticky at first and gradually becoming supple and smooth. The earthy smells of garlic and rosemary vanquish the smell of stain in my nostrils. I turn the dough, kneading. The timer ticks off seconds and minutes. I clean the bowl, grease it, use a linen towel to cover it for rising. I put it in the oven for safe keeping, because the cats are likely to lie on it or step in it, or nibble at it if I leave it out. The bread, like the pallets, is a project in stages. I don’t have to focus on any one step for more than a few minutes. I move between the kitchen and the back yard with my phone, not thinking, not planning, just taking the next step, and the next. I can’t remember times, so I write them down. About 90 minutes for the stain to dry. An hour for the bread to rise. Another 90 minutes for the pallet to dry. Another hour for the shaped loaves to rise. Another 90 minutes. An hour for baking.

Photo by Helena Yankovska on Unsplash

At the end of the day, I have two enormous round loaves of bread to cool, slice, and put in the freezer. This batch will last me for a year. I have finished another pallet. I leave it on the sawhorses to dry overnight. My stained hands smell like garlic.

I haven’t cried since the last night call, my brother telling me Mom was gone. Perhaps I cried all my tears before she went. I receive condolences with all the grace I can muster. People talk to me about God and heaven. They talk to me about Mom. They talk to me about their own experiences of death. I try to be gracious. I try to look like I’m listening, like I’m there. With my brother and sons, my partner, I can be real. The faces of my friends comfort me. They don’t need anything from me. They don’t ask for anything. I can see their concern, their love for me, their sorrow. They hug me, and smile. They talk to me about small things, the daily things I’ve lost track of – family, friends, outings, work. I pick up a friend’s daughter and feel almost normal, doing an ordinary thing, a manageable task I cannot fail.

I realize part of my feeling of unreality is rooted in a loss of identity. I catch sight of myself in the bathroom mirror and pause. I rarely look at myself in the mirror. This woman, who is she? She isn’t the disappointing daughter any more. She can’t be, if there’s no mother to disappoint. What else is she? Who else is she? I look into my own eyes and feel no shame, no guilt. Did Mom take them with her? How will I navigate my life without them on my shoulders, without the knowledge that Mom is alone, suffering, needing? For fifty years I was at her side, day and night, year after year, ineffectual, helpless to fix or heal her physical pain, her dysfunction. Feeling my failure, my powerlessness, knowing I more often made it worse than better as time went on, even though she clung closer and closer to me as she aged. She could not release me and I almost waited too long to release myself.

But the geographical distance I put between us brought no real release. She still suffered. She declined, grew confused. Her body aged and began to run down. She was just as lonely without me as she was with me, just as emotionally remote, just as relentlessly needy. She cut herself off from me, but I still carried her. Internally, I still orbited around her. I still agonized for her.

I still loved her. I always loved her. I accepted she could not find me lovable, but it made no difference. She was my mother, and I loved her. All I ever wanted was for her to be well, and happy, but I could not make it so, and in her eyes it was my responsibility to fill her need. Indeed, she told me long ago her physical pain started with her pregnancy with me. I accepted the blame, and was heartbroken, and have tried desperately to make up for it ever since.

Photo by Nicole Mason on Unsplash

Now Death has come to stop her suffering. Has mine stopped, too? I don’t know. I’m too numb to tell. But I feel different. I feel … released. I prayed for her release and freedom, not mine, but perhaps they were linked. Many times a day I think of her, hear her voice in my head, and I realize with a painful clench of my heart she’s gone. It’s over. I can’t humiliate her anymore because of what I wear, how my hair looks, what I do, who I sleep with, or, most of all, what I write. She’s moved beyond humiliation. I can’t fail her anymore. And that’s a soaring, joyful, unbelievable thought. I can’t fail her anymore.

I wonder if I’ll finally feel good enough, if I’ll do a good enough job, live a good enough life. Might I simply enjoy my small talents, my joyful work, my community, my garden? Might I immerse myself in the loveliness of life without the gnawing guilt of knowing I’m happy when she’s not, I’m companioned when she’s not, I’m relaxed and rested and peaceful when she’s not, I’m laughing when she’s not?

The last couple of times I spoke to Mom, I told her it was okay to rest now, she could let go, be at peace. We told her her loved ones and animals were well and happy, and she could relax.

I told her, and I meant it. Was I telling myself, too?

She could not release me, yet I am released. Did Death break the chains when he gathered her in? Or now, at last, have I released myself, now that she’s moved entirely out of my power and knowledge?

As I write this, it’s Wednesday afternoon. I have finished another pallet. I have written. I have sat in the sun, read a paragraph or two at a time of an old Edna Ferber novel, rested my eyes on the garden. The lily stems are turning dry and brown, as are the leaves. Sunflowers bloom. The sun is hot. The phone has been sitting on my kitchen table all morning, silent, as I go in and out. I have balanced my checking account, scheduled a private swim lesson in a home pool, ironed a tablecloth and three napkins. Tomorrow I go back to work.

A new page of my life has turned. I can’t read it yet. It’s enough to sit with it in my lap, letting my gaze wander over blue sky and afternoon clouds, the garden, our old cars, the worn wooden boards of the porch, the bruise on my left knee, the mosquito bites on my right arm, the smears of stain on my hands. It’s too bright in the sun to read this new page, too hot, too much effort. I’ll read it later.

I dare to be at peace.

Daughter’s Dream (July 2014)

I dreamt I carried my mother.

The car had slipped out of her control

with a blind will of its own,

and I thought

I knew she shouldn’t be driving.

We landed in water.

I swam to her and held her in my arms.

Then the water was gone.

I carried my mother,

but she left my embrace,

slipping free of her embattled flesh.

Irrevocably, I felt her go.

I was alone.

I carried the vacant body of my mother.

Empty beds stood all around me

but the sheets were disordered and dank,

Smeared with shit.

I carried the vacant body of my mother.

There was no clean place to lay her down.

I carried the vacant body of my mother,

seeking to slip into my own freedom,

seeking absolution.

To read my fiction, serially published free every week, go here:

by Jenny Rose | Nov 6, 2022 | Boundaries, Connection & Community, Emotional Intelligence

I’m sitting at my desk this morning, the sun shining on the wet grass scattered with wrinkled leaves outside my window. I’ve just been running errands. My desk, unusually, is piled high with scraps of paper, notebooks, my calendar, receipts, to-do lists, and a new binder and paper I just bought to help me organize. My big grey tabby, Oz, is busily knocking everything off the desk and chewing on a new plastic package of AAA batteries because I won’t let him lie on the keyboard.

Photo by Joanna Kosinska on Unsplash

I was sick most of October. I’m finally on antibiotics; I can breathe, and consequently think, more clearly. A week ago an aged family member living halfway across the country with whom I have a lifelong troubled history became openly unable to manage their life and then fell and broke their hip in quick succession.

Sometimes life requires us to muster every bit of learning, wisdom, strength, courage, insight and experience we have in a catastrophic practical test, like a nightmarish pop quiz. This is one of those times. It helps to look at it that way, because I know I have (somewhere) everything I need to manage this situation with all my considerable compassion and clear-sightedness.

This last week I let go of everything. My living space needs to be cleaned. I desperately want to change my sheets after so many nights crying, coughing, and trying to breathe adequately enough to snatch some sleep. I’m longing to escape my phone and laptop, sit in the sun, read, relax, do some gentle gardening (still like late summer here in Maine). I haven’t even started on this post yet, a thing I usually do during the week.

I made it to work. I made it to the doctor for antibiotics. I stayed hydrated. Aside from reactive crisis intervention and coming to terms with what’s happening long-distance, that’s about all I can say for myself. But now, at last, I’m beginning to stir feebly into some kind of normal experience again.

It’s a relief.

I opened this document and started typing without any plan whatsoever. I don’t have to post today on this blog. It wouldn’t matter if I didn’t. I suppose I’ve grown used to the opportunity to organize my life into words every week.

For nearly a decade I’ve worked intensively on boundaries. Ten years ago I knew nothing about personal boundaries. My life was accordingly dysfunctional. It was hardly my life at all, in fact. It was everyone else’s life. I’ve written extensively about boundaries on the blog, and the concept of the difference between your experience and mine is woven heavily into my fiction. I’ve practiced building and maintaining healthy boundaries in the last years, though I’m still far from perfect in working with them.

But I’m getting better all the time.

When we are prevented from building appropriate psychological boundaries as children, we never create an internal world in which we can rest, center, and ground. We become an image in someone else’s mirror, a paper doll, a nonperson.

Nonpeople have no needs, no credibility, and no permission to express themselves as individuals. It’s worse than no permission, though. Nonpeople are severely punished for any independent feeling, need, or expression. Nonpeople have no private life. They’re not allowed to say no.

This kind of relationship, sadly, is often invisible to onlookers. From the outside, such connections look bonded and mutually adoring. The public view never sees the anguish involved in a relationship without boundaries.

Anguish on both sides. Those who seek to prevent others from having boundaries are deeply damaged, insecure people whose own boundaries were likely brutally violated and torn down. They are terrified of being alone, and a boundary makes them feel utterly outcast and rejected.

Photo by Nicole Mason on Unsplash

But for me, boundaries are sanity. They’re safety. They allow the power to choose and respect to flow both ways. They say, “My self is worthy. Your self is worthy. We can choose to love one another as well as ourselves.”

Reshaping a primary relationship with no boundaries into one with healthy ones is excruciating. It may not be possible. I haven’t decided it is impossible, but I wonder. One of the hardest things about it is how it looks to outsiders, who don’t understand why all the harsh edges and corners are suddenly showing in such a perfect, loving relationship, the kind we all want, the kind we should feel lucky to have.

Another feeling I’m present with just now is the nauseating swing between relief and guilt. All secrets, painful family secrets included, have an uncomfortable way of being revealed. Even if everyone involved conspires to keep the secret, eventually, often in a you-couldn’t-make-this-stuff-up kind of way, someone or something like a terrible series of events exposes it.

I’ve posted about such ideas as loyalty, responsibility, duty, gaslighting and projection. The bars of prisons built by family systems are forged out of concepts and strategies like these. But when a secret escapes the bars melt away and we’re suddenly free. We’re not alone in solitary anymore.

Some stranger says to us, “Oh, yes. I’m familiar with that dynamic. I’ve observed that behavior. I understand,” and we realize we are not crazy. We are not mean and ugly. We are not hateful.

We are not alone.

The relief of validation is indescribable. So is the guilt accompanying the relief. When we guard secrets, literally with our lives, for the sake of protecting the dignity of a loved one and the secrets are revealed through no fault of our own, we also feel exposed. The mere fact that we were the designated secret keeper means we failed.

Our love and the cost of bearing the secret’s burden for so long doesn’t matter. The least we can do, the least we can do, is remove all the boundaries we’ve erected so carefully and painstakingly and once again give up our lives, our freedom, our selves. Our loved one’s anguish should become our anguish, their pain our pain, their limitations our limitations. If necessary, their death should be our death. Because we betrayed, we let them down, we failed.

The secret got out.

I can’t see very far ahead. It’s not useful to gaze at the road behind. I’ve already walked it and everything is different now, the people involved and the situation. Right now I know where I am. I can see the next steps. This is a new path, one I’ve never taken before. It’s a new script, a new experience. I’m working on releasing my assumptions. I don’t know what will happen next. I can predict, but predictions make me tired. What I have is right now, today. I know what I will do today, both in my personal life and to manage my loved one’s situation.

This time I will find a way to inhabit my boundaries and support my loved one without sacrificing one for the other. I will make phone calls, send emails, get myself organized to do whatever I can long distance and prepare to travel in case of need. I will grieve.

I will also write, get outside, do some laundry, maybe take a nap, and work on recovering my health, because mine is the only life I can live.

To read my fiction, serially published free every week, go here:

by Jenny Rose | Sep 11, 2022 | Choice, Power

Probably every child is told we all have to do things we don’t want to do.

Photo by Cristina Gottardi on Unsplash

Children are concrete, and I was no exception. When I heard we all have to do things we don’t want to do, I thought it meant that’s what life was supposed to be about, a kind of slavery to all those things we don’t want to do. No one talked to me about balance, or doing the things we do want to do.

It made life seem like an unhappy business, years and years of unending duty, responsibility, and doing what I didn’t want to do. No recess. Or maybe what I really wanted to do was bad and wrong? Maybe I should want to do what I didn’t want to do. I wasn’t sure. A part of me went underground. I didn’t want anyone to know how bad I was, how flawed. I worked hard at the things I didn’t want to do and hid the things I did want to do, in case they were wrong.

But I couldn’t conceal the feeling of wanting and not wanting from myself. I used to make hidey holes in whatever house we were living in at the time and go to ground with a book, but I always felt guilty. I wanted to read. Doing what I wanted to do was bad. I should have been helping my mom do all the things she didn’t want to do.

The pronouncement that we all have to do things we don’t want to do is stated as a Cosmic Truth, especially as an adult tells it to a child. It’s loaded with feelings and experience a child can’t possibly understand, but the subtext was clear to me:

Life is not much fun.

I can’t resist picking apart Cosmic Truths as an adult, and as I think about this one it occurs to me it really has to do with personal power more than wanting or not wanting. It’s not framed in terms of personal power because our emotional intelligence is so low. Making choices based on whether we want to do something or not is childish. Power resides in the act of choice, not in the wanting or not wanting.

Steering our lives solely by our desires is hedonism, a belief that satisfaction of desires is the purpose of life. Desire, though, is so shallow, so fleeting. And it’s never permanently satisfied. No matter how well and pleasurably we’ve eaten, we’ll be hungry again. Desire is a treadmill we can never get off.

This is not to say we shouldn’t ever choose something we want or say no to something we don’t want, but our desire is easily manipulated. That’s why advertising works. If we can be easily manipulated, we’re not standing in our power. Addiction is based, at least in the beginning, on wanting and not wanting.

A more useful question than What do I want to do? is What would be the most powerful thing to do? We might want to eat a carton of ice cream, but a walk feeds our health, well-being, and thus personal power much better. After all, one carton of ice cream leads nowhere but to another. Personal power can lead us to joy and experience a carton of ice cream never dreamed of.

- If we don’t choose to do difficult, frightening, or new things, we’ll never grow.

- If we don’t choose to take care of our bodies, they won’t function well.

- If we don’t choose to be self-sufficient and resilient, we’ll be dependent.

- If we don’t choose to learn anything, we’ll remain ignorant.

- If we don’t choose to plan ahead, prepare, or manage consequences, we diminish our choices, waste resource, and weaken the contribution we’re capable of making.

- If we don’t choose the responsibility of commitment and making choices, someone else will make our choices for us.

And so on.

I’m changing the frame. I’m less interested in what I want and what I don’t want and more interested in how my choices affect my power, and the power of those around me. I’m willing to do what I don’t want to do if it’s a step on a road leading to integrity, power, healthy relationship, or anything else important to me. At the same time, I can exercise my right to say no to things that won’t take me where I want to go.

It’s about power, not desire. Any three-year-old can want and not want. It takes an adult to manage a healthy balance of personal power.

Photo by Deniz Altindas on Unsplash

by Jenny Rose | Apr 23, 2022 | Emotional Intelligence, Feelings

All my life I’ve been told I overreact and I’m too dramatic, two labels which automatically invalidate my experience, feelings, and any attempt I make to communicate honestly.

Being told we’re overreacting is a sure way to shut us down, especially when we hear it regularly. It makes us question our own experience. It breaks connection and trust. It isolates us in shame.

It’s an insidious form of gaslighting.

Photo by Jonathan Crews on Unsplash

When I went through emotional intelligence coaching, I understood being told I’m dramatic is code for, “Your feelings make me uncomfortable.” It’s not a message about me at all, it’s a message about the person with whom I’m interacting.

As a child, I believed I exaggerated and I was too dramatic. I pushed my feelings down and hid them. I didn’t respond to my own distress. I didn’t ask for help. I trusted no one with my real emotions. I taught myself to become stoic and uncomplaining, to focus on the positive, to carry on no matter what.

My feelings became my enemies. I was deeply ashamed of them. They were bad and wrong and they hurt other people.

Now, decades later, I think a lot about feelings as I struggle with my re-triggered autoimmune disease. I know my current physical pain mirrors my emotional pain, which consists of passionate, intense feelings. Learning to manage those feelings more effectively is a work in progress. I do well with one at a time, but right now I’m overwhelmed with emotion. Emotional overwhelm is the trigger for physical pain. I keep right on keeping on through difficult feelings, but once the anguish is translated into back spasm, I can no longer hide or ignore my pain. Everyone else can see. Everyone else knows. I can’t hide my physical disability.

My body betrays me.

Horrors. I cringe, waiting to be told I’m too dramatic and I overreact. My feelings are wrong. They make others uncomfortable. They’re shameful, immature, crazy. I have nothing to complain about. Others have much harder lives than I do. It’s my business to support, not ask for support.

But my body tells the truth. Physically, everything hurts.

The truth beneath that truth is my heart hurts. I’m scared, I’m angry, I feel alone, I feel supported and horribly vulnerable, I’m excited about new beginnings, I feel guilty and ashamed about struggling, I feel relieved, and I don’t know how to bear my grief, both current and past. But I’m still too distant from my feeling experience to encompass all that, let alone manage it effectively.

Photo by Cristian Newman on Unsplash

So, back pain.

In the middle of this experience, I read an article by Courtney Carver from Be More With Less titled “5 Thoughtful Ways to Help You Underreact.” As you can imagine, it caught my eye.

Every day I think about this list of five strategies, and the difference between overreaction and feelings.

Overreaction is defined as a more emotional response than is warranted. Who decides what kind of an emotional response is warranted? Some people feel things very strongly and vividly; others do not. Certain events and situations trigger deep emotions for all of us. Do any of us have a right to judge another person as overreacting, especially when we can’t possibly know the entirety of their private emotional experience? Certainly, some people appear to overreact frequently, but do we stop to ask ourselves, or them, for more information? What is going on? What is behind the perceived overreaction? What need is crying out to be met? What are the feelings involved in the overreaction?

Feelings are value-neutral raw data we’re all biologically wired to experience. They’re simple. Mad. Sad. Glad. Scared. Ashamed.

We’re largely not in control of the complicated neurological and chemical experience of our feelings. We are able to control how we think about, express, and act out our feelings.

Thoughts and feelings are not the same thing.

I’m familiar with some of the strategies Carver writes about in her piece, but I’ve never seen such a concise and useful list of ways to manage habits of thought leading to “overreaction.”

It’s not our business to be concerned with onlookers who attempt to shut us down because of their own discomfort with feelings. Our business is learning how to refrain from shutting ourselves down or allowing anyone else to do so. Our business is taking care we don’t hurt ourselves as we feel our feelings.

Here’s Carver’s list:

- Do what you can. Let the rest go.

- Determine if any action or reaction is useful or effective in the first place. Does this deserve my time and energy?

- Don’t take anything personally.

- Distinguish between inside and outside. We can’t control what happens outside us. Our power lies within us.

- Closely related to the last strategy, if we feel we’re overreacting, what else is going on? Are we sick, hurt, dealing with unfinished feelings or unhealed wounds, struggling with addiction, lonely, tired, hungry? We need to focus on supporting ourselves.

Some people don’t want to deal with feelings, their own or anyone else’s. I understand. Such people will always struggle with someone like me, who feels deeply and expresses vividly. To them, I will always look as though I’m overreacting.

What overreacting means to me, though, is the intensity of my feelings is negatively affecting my health, and I need to find ways to support myself. I don’t want to feel less. I want to feel better.

Photo by Ben White on Unsplash

by Jenny Rose | Mar 26, 2022 | Emotional Intelligence, Feelings

Courtney Carver from Be More With Less suggests the feeling we call guilt may in fact be discomfort.

What an interesting distinction. I was immediately intrigued.

Guilt is defined as feeling responsible or regretful for a real or perceived offense.

A real or perceived offense.

Photo by Cristian Newman on Unsplash

If you’re someone like me, you feel almost everything you do and say is some kind of a breach of conduct, especially things like saying no, meeting your own needs, and setting boundaries. This feeling is based on past unhappy/critical/invalidating reactions of others to my actions. If I’ve Failed To Please, I feel guilty. I feel guilty even when I know I’ve done the right thing for myself.

So what if that feeling isn’t guilt at all? What if it’s discomfort?

Changing habits is uncomfortable, no doubt about that. Habits are effortless, especially mental and emotional habits. They feel like our friends. They’ve been with us a long time. We’re attached to them because they’re easy and familiar. Whether or not they’re effective or useful is not the point. How they affect others is of no interest.

They’re easy, and they’re ours.

The thing is, our habits don’t belong to us so much as we belong to them. We can stop them any time, we tell ourselves and everyone else. If we wanted to. But we don’t want to.

So there.

Breaking habits takes intention, focus, and determination. Support helps, but sometimes it’s unavailable.

So, do we feel guilty because we’re making different choices than our habits dictate, or do we feel uncomfortable because we’re making different choices? Making different choices affects those around us, and when things start changing, people get uncomfortable, especially if the change wasn’t their idea. Most people are sure to tell us when we “make” them uncomfortable.

Then the guilt starts.

Maybe discomfort, theirs and/or ours, is a good sign, a sign we’re truly doing the work of change. Maybe the guiltier/more uncomfortable we feel, the more successful we are.

Maybe we shelve the guilt and welcome the discomfort.

Sometimes we all do something we know is wrong and guilt helps us learn and make amends for our choices. Sometimes. Not every day, all day.

Being alive, taking up space, growing, learning, and reclaiming our power and health are not worthy of guilt. Uncomfortable work, yes. An offense, a breach of conduct, a crime, no.

When I feel that old familiar guilt come knocking, I’m going to look at it more closely. Maybe it’s not guilt at all. Maybe it’s just discomfort.

Photo by Gary Bendig on Unsplash