THE WEBBD WHEEL

OVERVIEW & EXCERPTS

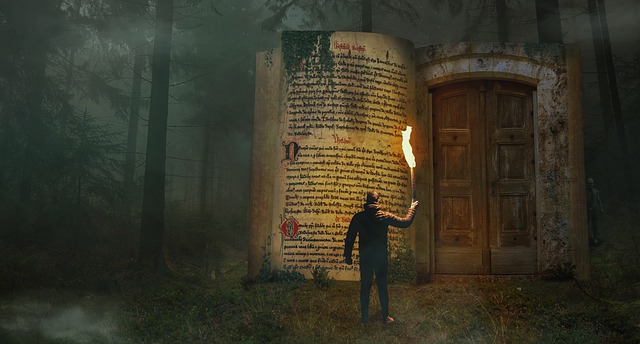

This extraordinary body of work breaks new ground and crosses genre lines. Part fantasy, part science fiction, part systems science, part women’s studies, and wholly fascinating, it’s a complex tapestry of characters and stories revolving around the breakdown of the natural world on the planet Webbd. Reminiscent of guides and teachers such as Joseph Campbell and Clarissa Pinkola Estes, these books take the reader on a journey through the human experience of birth, relationships, breakdown, death and renewal.

Beautifully textured and embellished with mythology, legend, symbology, and occult from around the world, Jennifer weaves an extraordinary tale of choices, consequences, learning, resilience, complexity, and ultimate redemption. The Webbd series is filled with familiar characters from folk, fairytale, and oral tradition, as well as new characters and stories entirely her own. Structured around the pagan Wheel of the Year and Tarot cards, the story of Webbd is sprinkled with magic and marble lore.

Readers will be entranced by dwarves, shapeshifters, merfolk, gods and goddesses, and unforgettable animals as the cast of characters connect, cooperate, solve problems, conflict, and face personal and social challenges.

The Webbd series brings together those concerned with complexity, permaculture, holistic management, emotional intelligence, feminism, identity, authoritarianism, spirituality, social power dynamics and relationships, and the ways in which our stories shape our lives.

The Webbd Wheel is currently published serially in Substack on Jennifer’s new site, A Stone, a Web, a Story. A free subscription allows you to read weekly installments of the books, access archives, and get a behind-the-scenes look at how these books were created with weekly posts. If you are interested in subscribing, follow this link, and thank you!

It begins with the Hanged Man.

Harvest passed through his hands, but they’re slack and empty now, scarred from picking, mowing and cutting the yield. He existed in the kiss of stone and blade, the rapturous sickle shape of the scythe. He inhabited callus, gash, thorn, wasp sting and torn fingernail. His sweat oiled the handles of a thousand tools. His blood and seed oozed out of discarded sinking fruit, smelling of rot, on the parched stubble.

Now comes peace after mighty effort. Blankets of snow are soon to cover November’s bony bed. The Hanged Man rests, dried and diminished in loose nakedness, dangling upside down by one leg from a skeletal bough. The snake, Mirmir, wraps around the branch, anchoring the Hanged Man, his flat head swaying near the man’s gold-ringed ear.

Mirmir murmurs of what might be and what might not be, what has been and what has not been, of time past and coming again soon. He whispers of worlds like glowing marbles turning through dark space, blue and green, grey and brown. Each world is a long, long story; each life a shorter one. The stories are bound, one to another, a net of star and crystal flung across the cosmos, linking one world to another so the leaves at the top of Yggdrasil, the Tree of Life, intertwine with the stars, each to tell, each to listen.

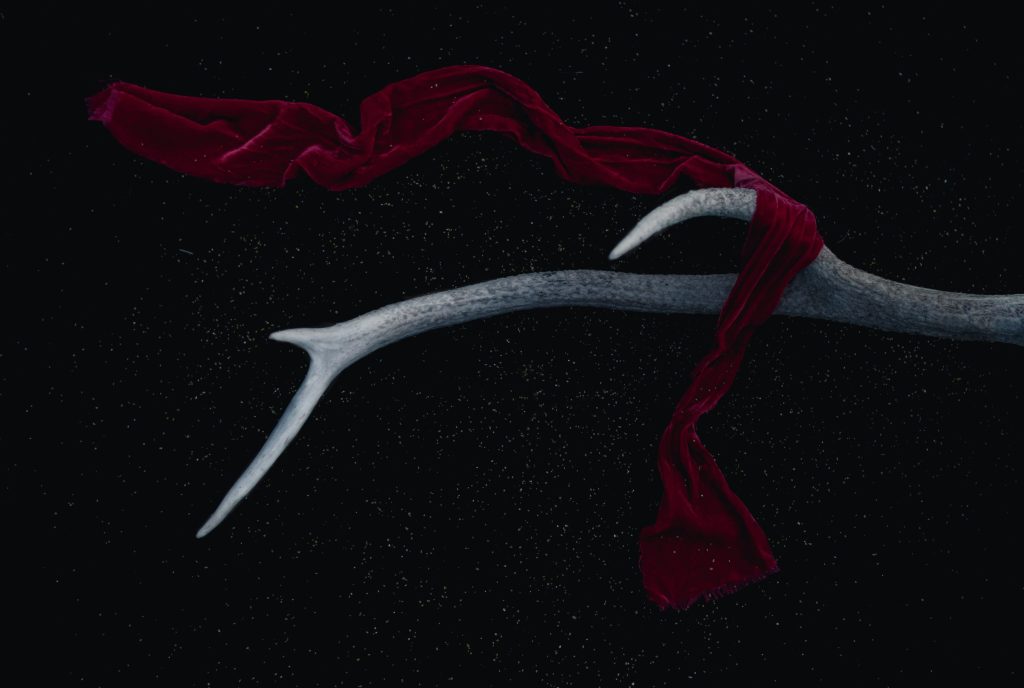

In this tree, on this small planet called Webbd, a crimson cloak hangs, a thin worn leaf of glory, sieving chill wind, fluttering, as leaf, snake, man, star and story revolve in endless dance, here at the turning point.

The Hanged Man listens. And he smiles.

(From The Hanged Man: Part 1: The Hanged Man)

MIRMIR

“In all timess and placess live thosse who ssee what’ss hidden,” Mirmir whispered, sounding like dry leaves rustling. “Their ears hear the prayers of the heart better than the prayers of the lips. They visit altars in forests, on moors, on hearths; altars decorated with symbol and rune, a pack of shabby cards, a handful of sticks or bones. Old women wait at crossroads with a gift. Uncanny peddlers spread their wares. Crones spit on a handful of marbles like jewels, galaxies in their eyes. Musicians walk with enchantment in their packs. And an old man with a staff, a cloak, and a weathered and worn hat tilted to hide an empty eye socket, wanders here and there, seldom speaking, his one eye seeing more in a day than any other two in a lifetime.”

“Odin,” sighed the Hanged Man. Sunlight shone through the tired gilt of a few remaining leaves and fingered his thin hair.

“Who knowss the thoughtss of thosse collectorss of sstoriess and prayerss?” Mirmir continued. “Who can gauge the depth of their wisdom or humor? How far behind and how far ahead do they see? And if Persephone, in her frustration, and Hades, in his anger, are offered a choice, a risk, a chance to change their lives, will they take it?”

“Tell me how it was,” said the Hanged Man.

(From The Hanged Man: Part 2: Mabon)

The stag turned and dipped its head to the stone basin, drinking. She bent and cupped water in her hands and drank also. It tasted fresh and sweet, not as cold as she’d expected, smelling of fallen leaves. She laved her face with it gratefully, using the tail of her scarf as a towel. When she turned back to the White Stag a man stood looking at her out of the same calm, dark eyes. Without thought, she picked up a fur and draped it around his shoulders, for it was a cold night of snow and he was naked. They stood, face to face, and she trembled. He lifted her hand, opening the cup of her palm and putting his mouth to it. She felt flick of tongue, breath, and then, gently, teeth on the mound beneath her thumb.

Her knees loosened and she staggered. He swept her into the crook of his arm and knelt, laying her in the bed of leaves and bracken on a fur. She looked up into those eyes, those terrible, beautiful dark eyes. Together, they loosened her clothes and let them fall away. She felt desire, yes, but something deeper than that cried out to be held, to be comforted, so that the richness of desire, awful vulnerability and need for nurture wove together, overwhelming her. In that moment, she acknowledged her fear of being old and unseen and couldn’t bear the grief of it. She clung to him, the stag man, clung with all her strength and opened herself to the dreadful shattering wave of emotion, wise enough to know if she fought against it she’d be broken to pieces.

After a time, she became aware of the steady strong beat of his heart in her ear. It called her home, back to her body, back to this sheltered forest hollow. She let it surround her even as his arms did. It seemed to her it was the forest’s heartbeat. He breathed quietly and her own breath slowed, comforted by the nearness of another. Her fingers ached from the strength of her grip on his body and she loosened them, understanding herself part of a greater life that held her tenderly and would never let her go. She took in a deep breath. She could feel his hands now, pressing against her back, holding her firmly. She breathed again, feeling her breasts against his chest, feeling her belly push against him. Oh, to be held like this! To be held by something stronger than oneself! To give up responsibility, just for a while! To be allowed to be weak, to be afraid, to be tired! Again, tears welled in her eyes from what felt like her very roots, tears of gratitude for rest from the work of being brave. With those tears, weariness filled her as a slow tap fills a sink. She was warm. She was safe. She wasn’t alone. She settled herself yet closer against his body and felt one of his hands move away from her. The gentle weight of more skins comforted her and he tucked them in around their shoulders and sides and slid his hand under them to hold her against him again. She slept.

She dreamed. She dreamed a leaf, clinging to life and then surrendering and falling, falling gently, dancing, and alighting in a new life… She dreamed of ivory-colored antlers, twined and woven into an intricate pattern and holding innumerable candles, shining and gleaming like stars, like snowflakes… She dreamed of walking down into the earth’s body past layers of bracken and leaves, still smoldering with color like embers, layers of tired white bones–or were they antlers?–that became brown and copper and russet of roots and then rocks, buried and unseen but holding up the roots … She dreamed of a handful of leaves, dry and fragile, with their scent of old things, and the rough feel of a tree trunk against her cheek.

She dreamed a handful of black seeds. They were cold, like chips of ice. They burned her flesh with their cold. She felt afraid of them because they were death. They were utterly dead and cold, dry and hard. She wanted to cast them away. It seemed as though her hand would never again be warm or free of their chill. Her hand wouldn’t turn over and release them. She couldn’t let them go. As she looked in horror at the palm of her hand where they lay, she saw a fragile thread of light, golden and warm, and then another and another. The seeds cracked open, releasing light, rich and beautiful. One by one the seeds opened until her palm held a web of light and warmth.

The light winked out, and against her cheek she felt the short white coat of an animal, coarse and oily, smelling wild.

She dreamed of being uncovered in a dim place, but not alone, for she was touched. Every bump and scar and line, every hidden fold and cleft was smoothed and explored. She felt breath upon her body and knew he drank her scent. She felt hands, lips, long strokes of a tongue. She felt skin and bone and hair. She felt utterly loved, utterly cherished. She felt seen. She felt recognized. She felt known. She’d never known such depth of love, such tenderness, such regard. She slept.

(From The Hanged Man: Part 2: Mabon)

Creirwy hadn’t been expected back for three days, so it wasn’t until five days later that Morfran found her body. He was alone. He and Ceridwen had searched from the air for two days for some sign of Creirwy. Ceridwen wheeled away in the shape of a sharp-sighted hawk while he, in his favorite crow shape, flew low over the hills. The gleam of her hair revealed her. The golden color didn’t belong to autumn’s duns and heathers.

She lay in a hollow in a fold of hills. A nearby ring of stones on blackened earth showed signs of recent fire. She lay in a ring of poisonous false parasol mushrooms, easily recognizable by their flattened whitish caps and brown scales. Her clothing was thrown aside and her skin was dry and leathery, intact but empty, it seemed, of anything but bone. Animals and birds had not disturbed her body. He stood looking down at her, feeling nothing. His face was cold.

Disconnected thoughts drifted in his mind like an old tattered cobweb in an air current. He couldn’t look away from the thing on the ground. It wasn’t Creirwy. It couldn’t be Creirwy. Creirwy was life, and the shape lying in the bracken was without life. Where had she gone, then? Was this cast-off remnant a joke, or a trick? It was cruel. Who had defiled the familiar hills of his home with such a twisted ruse? He had a dislocating sense of sinister and unfamiliar influences at work in the world.

Evil. His mind lingered on the word. It reminded him of something recently seen, recently discovered.

He tore his eyes away from the body and raised them to the surrounding hills, turning slowly on the spot. He began the familiar, comforting ritual of allowing his vision to blur and breathed in the scent of earth and the autumn tapestry of plants. He opened his mind until he could hear the scratch of insect steps, wing beats of birds high above in the sky, the many-voiced wind, the far away silvery song of stars.

Without haste, without effort, he saw the glowing campfire under an enormous starry night sky. Blankets and sheepskins lay on a springy patch of heather. He smelled roasting mutton. He heard laughter, rich, warm. Creirwy’s laugh. A woman’s laugh.

He saw a shadow darker than night, a shadow concealed within flesh and bone and blood. It was made of voracious, lustful hunger salivating and groaning with desire, but not for flesh. It wasn’t akin to the woman’s radiant laughing invitation. No, this was a predator of… something rosy and warm, luscious as a ripe nectarine, glowing in the sun…No! Not life, but light! Light! It craved innocence and light!

The jolt of understanding brought him back, nauseated and sweating, and he fell to his knees next to Creirwy’s body. He knew a fleeting moment of relief that she hadn’t been violated physically, but cold horror at the spiritual violation that had occurred—and it was his fault. He’d known a monster with a blue beard hunted in the hills near Bala Lake, and he’d said nothing. He’d seen the disturbance in Creirwy’s flickering light, but hadn’t been alert enough to find out more, to warn his parents, to put the pieces together and discover the truth.

Somehow, Creirwy had met this thing, formed a relationship with it, and hid it from all of them. Somehow, Creirwy had grown up, become a young woman with desires and thoughts and dreams. She’d become a woman with a private life and the power to make choices on her own. And he’d missed it. He, with his clear sight, had failed to see what was right in front of him. In his arrogance, in his self-sufficient mastery, he’d thought of her as nothing but a helpless child, loving and pretty, but not…not…not a whole person like him!

He put his face in his hands and wept.

(From The Hanged Man: Part 3: Samhain)

After the wedding, Jenny moved into Hans’ house and began cooking his meals and doing his laundry. When she and the baker went out, she recognized envy on other men’s faces without being much interested. She lay next to Hans each night and made her body available, as though renting an empty room.

Jenny’s life became a series of choices governed by what a good wife would do. She tried not to think of spinning. She had no money to buy wool or flax or hemp, and Hans had no idea she possessed this skill. He gave her money for housekeeping and kept track of every penny. She put away thoughts of Rumpelstiltskin and the past. She told no one of her ability to spin straw into gold. Living with Hans reminded her of living with her father. Hans was a vain man who wanted an easy life. She’d have no peace if he knew what she could do, and she’d no desire to feel again what she’d felt the night in the castle cell with Rumpelstiltskin.

As weeks and then months passed, she tried to be content. She’d followed the rules. She had a husband, a home to keep. Her life was full. There would be children.

She was aware of Hans’s anger, for it fed her own. When he invaded her body, laboring over her, his hot breath in her ear, she took his anger with a kind of fierce greediness and added it to her own. She made a stone cell in her mind like the cell where she’d spun straw into gold. In this cell, she secretly stoked her rage. Here she hoarded herself, spinner, maker, creator. Here she kept the memory of a cradle song her mother had sung to her before she died.

Hans began to berate her. She was cold. She was hard. She was high and mighty. She was an imposter, with her fine speech, her manners and her dignity. What was she, after all? She was no lady. He’d heard rumors she had been the plaything of some king, and he had cast her aside. And what of her people? Who was she? Where did she come from? Why was she alone in the world?

In time, he grew incapable of using her body and he blamed her, calling her unfit to be his wife. “I knew you weren’t good enough for me! I knew it! But I let you get around me with your looks and your false pretentions! What a fool I am! You couldn’t even pass the test!”

Generally, she ignored this kind of talk, but the last thing he said caught her attention. She remembered the overheard conversation in the inn, the snickers, the nudges.

“What test, Hans?”

“The test! The test of a true lady, a great lady. The kind of lady I deserve!”

Patiently, “What kind of test?”

“The maid at the inn hid a pea in your bed! A hard pea laid under your mattress and feather bed and you never even felt it! You slept every night like the coarse peasant you are on top of that pea. Why, a true lady would be black and blue! A sensitive, fragile-skinned lady would be unable to endure such a thing!”

Jenny actually laughed. “How ridiculous you are! Who told you that? I thought you were looking for a wife, not a fairy princess!”

He struck her across her laughing mouth.

Jenny found herself on the floor. She didn’t remember falling. She’d been laughing, laughing for the first time in months, and then something had happened. Her face felt funny. She put a hand to her mouth and it came away bloody. Hans stood over her. She saw his face clearly, so clearly it almost hurt, like a too bright light. She’d never seen him so clearly before. She felt as though she’d suddenly stepped out of a numbed and foggy dream into bright daylight.

She thought, so my heart is still with me, and alive!

And then, where is Rumpelstiltskin?

And then, what am I doing?

“How dare you laugh at me, you bitch?” roared Hans. “Who do you think you are?”

I’m a woman, thought Jenny. She regained her feet and stood facing her enraged husband. I’m a spinner. I can spin straw into gold. My mother loved me. Rumpelstiltskin loves me. I’m Jenny. She wiped blood off her mouth with the back of her hand.

He raised his hand again and her own shot out like a snake and closed around his forearm, halting the blow. She looked into his eyes without speaking. He glared, and then his gaze dropped. He pulled out of her grasp and turned away, head hanging.

(From The Hanged Man: Part 3: Samhain)

He lay there, stars filling his eyes, sound of the river in his ears, feel of her hand covering his, and he heard truth in her words. He looked up at the flickering lantern flame and shape shifted into a moth with fragile dusty wings. He joined other moths attracted by the light in a fluttering dance, but for him it wasn’t a dance of self-destruction. He danced for joy.

She gasped as he shifted and sat up to watch him, lips parted as she followed his graceful movements. He flew down to her. In his moth shape, he was acutely aware of her warmth, her aliveness. Pear juice stained her fingers and lips with their scent. He flew about her head, brushing her cheeks with delicate wings. Lamplight fell on her amazing hair, loving it into shining strands of gold and silver. She raised her chin and closed her eyes as he flew around her, exploring her ears, stirring loosened tendrils of hair against her neck, brushing her eyelashes with his moth wings. He left her head and explored the soft skin on the inner wrists below her rolled-up sleeves. He fluttered around the thin gold bangles.

He left her arms and flew to the neck of her shirt, surrounding himself with her scent of clean earth, the grasses they lay on, the smell of cotton and the unique chemical imprint of her living body. Morfran felt drunk with it. She lifted her hands and loosened buttons, letting the shirt fall open. She lay back on her elbows, offering herself to his gentle, persistent exploration. He brushed against a nipple and she gave an involuntary gasp. He explored her breasts, flying in a fluttering circle around each of them, now and then brushing a nipple.

(From The Hanged Man: Part 3: Samhain)

He walked down to meet the incoming tide and turned to look up at the cliff top. He saw nothing but the ruined tower looking out to sea. He stood listening, careless of the cold surf washing first around his feet and then his ankles.

Then both drumming and singing stopped, leaving only the restless sea. Morfran didn’t move. He couldn’t move. Something must happen and he waited for it.

A figure appeared on the cliff top, right on the furthest edge of the finger of land jutting into sea. Morfran recognized the old man. He stood there, looking out to sea, silhouetted against the low sky. The naked figure radiated power and something else… Morfran kept his eyes on the figure but softened his gaze, breathed… Grief. Had the song been a lament, then? For whom did the old man grieve so wildly?

Then, with the grace and strength of a much younger man, the old man launched himself into a dive. Morfran cried out in shock. The figure seemed to hang in the heavy grey air like a bird, graceful and confident. Then the figure plunged into the pool surrounded by rocks, cleaving the water cleanly and disappearing.

Without thinking, Morfran shifted into crow shape. He flew up from the beach and over the pool but the water’s surface foamed and surged with the incoming tide and he couldn’t see below it. He flew low over the pool, shifted into the form of a fish and splashed into the water.

It was not like Bala Lake. The water felt strange, thick and buoyant. He could see nothing. The world was green and gray, bubbles and surge and foam. He swam deeper, into less tumultuous water, but still could see nothing, and the sea roared in his ears. Bala Lake had been utterly quiet. The powerful suck and surge disoriented and exhausted. He didn’t know what he hoped to do—help the old man? Save his life? In this wild water? He wasn’t sure he could save himself. Yet he felt frantic—panicked. He must find him! He must!

Then, rising powerfully underneath him on its way to the surface, thrust a huge fish. It was ten times, nearly twenty times his own fish size. As it slid past, he glimpsed a powerful tail covered in scales. He rose up with it and saw a man’s body, bare chested, and floating ropes of grizzled hair bound together with a thong.

The shock of what he saw jerked him out of his fish shape and back into his own. The transition felt abrupt and clumsy, almost painful. He took in a mouthful of saltwater. He kicked, trying to get his head above water, and a wave broke over him. He thrashed, trying to get his bearings. The tide pulled at him, then pushed. He could see nothing but waves and they slapped at him like powerful hands, confusing his senses. He couldn’t catch his breath. He felt completely helpless. Then an arm came around his chest and held him fast. Morfran’s panic receded. He wasn’t alone. Whoever held him so closely wasn’t afraid. He remembered he was a good swimmer and loved water. He filled his lungs with air and wiped stinging saltwater out of his eyes. The other was pulling him towards one of the rocks that ringed the pool. Morfran reached up and patted the arm in signal that he wanted to swim on his own. The arm released him and together they swam the few yards to the rock.

Morfran turned and looked into old man’s face. His eyes were the color of Morfran’s own, a clear, far-seeing grey. He wore thick gold hoops in his ears and there were scars on his shoulders and the arm that anchored him to the rock. He laid a hard, callused hand tenderly against Morfran’s wet, cold cheek. He smiled but tears slid out of his eyes and mingled with drops of seawater.

“Grandson.”

Morfran came into his arms like a child. The sea lifted and sank around them. They held fast to the rock and each other, and together they wept.

(From The Hanged Man: Part 3: Samhain)