by Jenny Rose | Mar 29, 2018 | Connection & Community, Emotional Intelligence, Shadows

As an oral storyteller, I’m committed to gathering old tales from all over the world and retelling them because they contain blueprints for life. Each story is a teacher, a small piece of code, a seed, a fragment of wisdom, a snippet of DNA. Stories speak to us about who we are, who we have been and who we might yet be. They speak in the voices of place, people, history and culture.

Photo by Alan Chen on Unsplash

Story does not exist without storytellers. Literacy is not necessary, as long as people remain connected enough to pass story on orally. A culture which unravels and frays in its ability to form healthy connections and bonds and at the same time stifles the acquisition and sharing of knowledge is in grave danger of losing stories, and when old stories are lost much of the collective wisdom of our ancestors is lost with them. We become crippled and impoverished. We lose our way in the world and we have to spend time and energy reinventing wheels we learned how to make hundreds of years ago.

As a storyteller, then, I come to you this fine spring week when the snow is ebbing in Maine, leaving behind rich, greasy mud, with the old story of the wolf in sheep’s clothing.

Every old story is in fact many stories. A piece of oral tradition is like a many-limbed tree. As it grows and matures it branches out over and over. Every teller who passes on the tale adds or takes away a piece of it, reshaping it according to the teller’s context in history and place. Still, the skeleton of the story remains recognizable, because the bones contain the wisdom, the old truth, the regenerative pieces reanimated over and over by those of us who share them.

The essential truth contained in the idiom “a wolf in sheep’s clothing” has appeared in many times and places. According to my research, the first time was in the Bible, in the Gospel of Matthew, as a warning against false prophets. The sermon goes on to suggest actions speak louder than words. Thereafter, the phrase was repeated in other Christian religious writing and from there entered into European vernacular. A Latin proverb arose: “Under a sheep’s skin often hides a wolfish mind.”

A 12th century Greek wrote a fable about a wolf who changed his appearance in order to get access to ample food. He put on a sheepskin and mingled with a flock of sheep, fooling the shepherd. The disguised wolf was shut up with the sheep for the night. The shepherd decided he wanted mutton for his supper, so he took his knife and killed the deceitful wolf, mistaking it for a sheep. Here is a branch in the story tree. The Gospel reference warns against deceitful teachers. The Greek fable warns evil-doing carries a penalty. The bones of the story — the consequences of a wolf disguising itself as a sheep — are the same. The story is now two-dimensional. Such pretense is dangerous for both wolf and sheep.

Another iteration occurs three centuries later in the writing of a 15th century Italian professor. A wolf dresses himself in a sheepskin and every day kills one of the flock. The shepherd catches on and hangs the wolf, still wearing the sheepskin, from a tree. When the other shepherds ask why he hung a sheep in a tree, the shepherd replies that the skin was of a sheep, but the actions were of a wolf. There it is again: Actions speak louder than words.

Aesop wrote two fables having to do with wolves gaining the trust of a shepherd and killing sheep, but the wolf is undisguised in these cases. Even so, the common theme is clear. A wolf is a wolf, and cannot be trusted with sheep.

In the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, Italian, French and English writers adopted versions similar to the early 15th century Italian tale, in which the wolf pretends he is not a threat to the sheep.

Most of us know the tale of Little Red Riding Hood, whose origins can be traced back to 10th century European folk and fairy tales. In the familiar modern version, a wolf disguises itself as Red Riding Hood’s grandmother and the innocent too-sweet maiden is fooled and subsequently eaten.

My favorite story of wolves and, in this case, goats, comes from my own childhood, the tale of the wolf and the seven kids (young goats). The mother goat must leave the house and warns her seven children about the wily wolf who might try to gobble them up. She says they will recognize her by her sweet voice and white feet, and they mustn’t open the door to anyone else. I was mightily amused by the wolf’s machinations in trying to fool the kids: Swallowing honey to make his rough voice sweet, whitening his black feet with flour. Of course, he does fool the kids and they are eaten, but, much like Little Red Riding Hood, the kids are saved from the wolf’s stomach in the end.

As an adult, this tale doesn’t seem nearly so amusing.

Lastly, modern zoology makes use of the term “aggressive mimicry,” which describes a method of deception by an animal so it appears to either predator or prey as something else.

I’m deeply troubled by what I see going on around me in the world. It appears many millions of people are no longer able to discern the difference between wolves and sheep, and this is creating dire consequences for all life on Planet Earth.

How did this happen? Why did this happen? When did this happen? How are we producing college graduates who don’t recognize wolves in sheep’s clothing? What kind of a so-called educational system, public or private, produces such myopia? For two thousand years we’ve understood the dangers of failing to clearly see the difference between sheep and wolves. Such a failure of judgement is bad for the wolves as well as the sheep. Tracing this old tale through time (when most of the world’s population was largely illiterate and uneducated), clearly shows us this is a learned skill. Little Red Riding Hood, the seven kids and several confused shepherds, all innocent, naïve, and inexperienced, had to learn to recognize a wolf when they saw one, or starve or be eaten. Critical thinking is not an innate skill. Parents, teachers and leaders must actively teach it.

Photo by Michael LaRosa on Unsplash

Here is a wolf. It’s an apex predator; intelligent, flexible and canny. The wolf is evolved to survive and pass on its DNA. It’s not confused about what it eats or the meaning of its life. Its job is to do whatever is necessary to survive and successfully reproduce. As a predator, wolves are an essential part of the complex system we call life. A healthy population of wolves benefits both the land and prey animals.

Photo by Jamie Morris on Unsplash

Here is a sheep. It’s an herbivore, a prey animal. It’s evolved to produce milk, meat and wool, survive and pass on its DNA. It eats grass. It too is an essential part of the web of predator (including humans), prey and plants. Its presence, properly managed, benefits the land and predators.

One can certainly throw a wolfskin over a sheep and say it’s a wolf, but that doesn’t make it so. Now we have a sheep in the throes of a nervous breakdown, but the animal is still a sheep. It still needs to eat grass. We cannot change a sheep into a wolf.

Likewise, a wolf wearing a sheepskin does not begin to crop grass. Wolves eat meat, no matter what kind of a skin they’re wearing. A simple shepherd might be fooled by a single glance in the dusk if the disguised wolf mills among the sheep, but five minutes of observation will quickly reveal the truth. Sheep do not tear out one another’s throats. A wolf cannot be changed into a sheep.

The wolves of the world, those who prey on others, naturally have a large inventory of successful speeches and manipulations. They study their prey and learn quickly how to take advantage of it. They are everywhere, in politics, religious organizations, schools and cults. They’re athletic coaches and businessmen, people of influence and power. They’re shadows behind conspiracy theories and cults like QAnon. They disguise themselves with projection and gaslighting, mingle freely with their prey and pick them off, one by one.

In the natural world, an overpopulation of wolves eventually runs out of prey animals. At that point, the wolf population goes down dramatically while prey animal populations recover. Nature seeks a balance of life, and if we create endless flocks of fat, stupid, blindfolded sheep, the grass will run out, wolves will increase, and slaughter will commence as the sheep begin to starve for want of food.

That’s a lot of destroyed land, dead sheep, fat and happy wolves and then, in the next generation, a lot of young wolves starving to death and, (one hopes) a few smarter and wiser sheep and shepherds.

People say we’re a superior species to wolves and sheep. I don’t see much evidence of that recently. We can’t seem to remember what we once knew well. We teach our children how to press buttons, look at a screen, and pass a standardized state test, but they can’t tell a wolf from a sheep, and neither can we. The wolves are not confused, but the sheep are milling around aimlessly like … well, like sheep, ripe and ready for slaughter. We’ve allowed ourselves to be brainwashed into believing our true nature is expressed by appearance, words and socioeconomics. Actions don’t count, and neither does DNA. Off we skip to the slaughterhouse, following honey-tongued wolves dusted with flour, who praise us for our compassion, compliance, inclusivity and political correctness while drooling at the prospect of all that food. Meanwhile, our planet degrades so no one else is properly fed and natural checks and balances are destroyed. Even the noncompliant, troublemaking sheep who manage to escape slaughter will starve. So will the wolves, eventually, after they’ve devoured everyone else.

Maybe then the complex system of life can begin to heal. I hope so.

In the meantime, I’ll be separating wolves from sheep and telling stories.

All content on this site ©2018

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted

by Jenny Rose | Feb 15, 2018 | Contribution, Emotional Intelligence

I’ve been trying to frame a post around generosity for several months. Interestingly and unexpectedly, the idea of generosity has remained a Gordian knot in spite of word webs, notes and lengthy simmering in the back of my mind. Since I began chewing on the idea of generosity, I’ve discovered Unsplash, a site offering free use of photographs for things like this blog, and now I finally feel I’m getting a grip on the subject.

Unsplash features more than 300,000 photos from more than 50,000 contributors. It’s free to use and free to join. Users may upload photographs for whatever they want as frequently as they want.

If generosity is unconditional readiness or liberality in giving, Unsplash is surely a fine illustration of the concept. The Internet is filled with people practicing their art. Some are trying to make a living. Many, like me, provide free content. Others start out contributing freely and then uplevel in order to earn a little bit of money with advertising, an Amazon affiliate program, a subscription fee, etc. In my view, some of the content out there is worth paying for, and other content is not.

Unsplash is worth paying for. Many of the photographers who contribute are professionals with content to sell, yet they continue to share some of their work freely with others.

Up to this point, I haven’t made a dime on this blog. It wasn’t about the money, but exercising my voice, my writing skills and my courage. I had no idea where it would go or what would happen with it. I had no idea if anyone would read what I wanted to write or how much I would grow to value the weekly practice of posting and maintaining a blog. I do want, however, to publish and sell my books in the future.

I think part of my struggle to get my head around generosity has been my own damaged sense of value. Those of us who feel we’re worthless assume we’ve nothing to give. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve declined attending a pot luck, a fundraiser, a party or even a funeral. I tell myself I have nothing to contribute, I was invited out of obligation or kindness, and nobody will even notice my absence.

Photo by photo-nic.co.uk nic on Unsplash

I am not Cinderella, and I do not possess a fairy godmother who will make me socially acceptable or worthy.

I wonder, looking back, if others have experienced me as being ungenerous or mean because of my lack of social contribution, when what was really at work was introversion, social anxiety and an abysmal sense of self-worth. I have no way of knowing.

On the other hand, I’ve volunteered my whole life. I’ve spent years working with children as a librarian, tutor, child development clinician, teacher’s aide, swim teacher and parent. I’ve participated in fire and rescue work as a volunteer EMT, as well as with animal rescue organizations. I’ve volunteered in libraries and as an oral storyteller, and I’ve volunteered as a dancer. I’ve worked in hospitals, nursing homes, public schools and libraries.

See? Nothing to contribute.

I earned a paycheck for some of that work, but one doesn’t get rich doing the kind of jobs I love to do, and the paycheck was never my motivation. I just loved the work. I felt as though I was making a difference in every one of those roles.

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

I’ve always limited the idea of generosity to financial resource. Part of my shame about my poverty is that I’m unable to be financially generous, which I’ve believed automatically makes me stingy and uncharitable. If my generosity is measured by what I spend, it’s so small as to be negligible. I’m a rotten capitalist consumer.

In thinking deeply about generosity, I can see how my beliefs have distorted my view. I wrote some time ago about the failure of money, and that peeled away some of my limiting beliefs, but only the first layer or two. If I make generosity about money, I can never be generous, and I block the financial generosity of others toward me because I can’t reciprocate in kind. My desire to give is greater than my desire to receive. I desperately want to make a contribution. I feel disempowered when I can’t reciprocate someone’s generosity in a way that feels equal, and then I disconnect.

Unhooking generosity from money changes the way I look at it. Developing some trust in my own value also changes the way I think about generosity. Now I wonder if money is perhaps the least reliable indicator of generosity, not the most. Money is very visible and obvious in the world, but that doesn’t make it the most useful contribution. There have been times in my life when I’ve been in desperate need of money, but many, many more times when I’ve been in significantly more desperate need of someone to hold me, someone to believe in me, encourage me and simply love me. Money is easier to come by, believe me, than love and acceptance. Writing a check, donating a few dollars to the organization of our choice or buying a gift is easier, for many of us, than effectively communicating our love and appreciation for those around us in words or actions.

Some people give only to receive. On the face of it, it looks like generosity, but it’s not. My understanding of true generosity is it has no hidden agenda. Conditional generosity is like conditional love; control and manipulation pretending to be something else. Behavior seeking power over others, or freighted with unacknowledged expectations, is the reverse of generosity.

Another way in which people use generosity to mask control is to force a “gift” onto another. In this case, someone informs us about what we need and we understand we’d better damn well accept it and be grateful. Refusal is out of the question because of an unequal power dynamic. Acceptance of the “gift” also perpetuates an unequal power dynamic, because we’re expected to demonstrate appropriate gratitude (as defined by the gift giver) for something we didn’t want or need in the first place. We’re not allowed to express or receive what we really need, only submit to what someone else needs to give in order to get something for themselves.

A good litmus test for discerning authentic generosity is whether it occurs in anonymity. People giving to receive will never do it quietly. There’s always a camera, a video, a witness or a headline. There’s always a score card, a quid pro quo. There’s always a distorted power dynamic. Such people give to reward and withhold to punish.

You want to star in my production? Meet me on the casting couch and maybe I’ll put in a word for you.

At the end of all this excavation, I’ve finally begun to make friends with generosity. I am capable of being truly generous, and I have generous people in my life. I can discern the difference now between the real thing and a ploy to maintain or grab power. I may not have money, but I can appreciate, marvel and share. I can say thank you. I can give anonymously. I can exercise a generous compassion towards myself and others for our weaknesses and mistakes. I can recognize my desire for reciprocity and power-with as important pieces of my own integrity and freely disconnect from people and situations that don’t support what I need.

This takes me back to Unsplash. I know in this day and age it’s hard to think past the money, but as a creative person on line with free content I can assure you no amount of money outweighs the gratification of knowing I’ve made a connection, that something I write resonates with someone else. Money is important, and I wish I had more of it. If I can uplevel the blog in small ways to earn a little bit of money, I’ll do it. The real reward, though, is when someone reaches out to me and says, “Yes! Me, too! Your words made a difference in my day.” It just doesn’t get better than that.

Because of that, I’ve developed a habit of contacting a couple of photographers every week whose work appears in this blog. Behind each photograph is someone living a life, struggling with the things we all struggle with, sharing their unique vision and eye with the world just because. Unconditionally. I go to their website, if they have one. I explore their pictures and read about who they are. I contact them and briefly introduce myself. I thank them for their collaboration with me, a collaboration invisible to them unless I reach out. I express my appreciation for their contribution. It doesn’t take very long. It’s not as fast as writing a check or reciting a credit card number, but it’s a lot more fun.

So far, every single one has responded to say thank you. Thank you for acknowledging my unique creativity. Thank you for taking the time to remember the person behind the camera. Thank you for collaborating with me so we enhance one another’s contribution.

Photo by Jeremy Bishop on Unsplash

There is no exchange of money in this generosity, only of humanity. They give freely. I accept the gift and add it to my own, paying it both forward and backward.

Generosity: Unconditional readiness or liberality in giving.

Please take a moment and meet photographers Jeremy Bishop and Annie Spratt.

All content on this site ©2018

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted

by Jenny Rose | Feb 1, 2018 | Connection & Community, Emotional Intelligence

Today is laundry day, and I’m sitting in the laundromat writing this week’s post.

I’ve always liked doing laundry. Turning a bundle of dirty clothes, sheets and towels into neat, fresh-smelling folded piles gives me a warm feeling of satisfaction and accomplishment.

At present, we don’t have a usable washer at home, so part of our routine is to hit the laundromat every couple of weeks. We know it’s time when my partner runs out of socks and I run out of underwear. At that point we collect dish and bath towels, sheets and clothing, and our stash of quarters and head into town.

Photo by Pop & Zebra on Unsplash

Sitting here, I watch a man open the mouth of a bulging cloth laundry bag and empty it into the machine. I see scrunched up socks, some more hole than sock; inside-out pant legs, whites, colors, sleeves and bandanas all tangled and mixed up together. He feeds in quarters, adds soap and sets the temperature to hot before heading back out, either to sit in his truck in the parking lot or otherwise kill time until the load is done.

I get a lot of pleasure out of the laundromat. Watching people deal with their laundry is every bit as entertaining as looking at someone’s bookshelves. Dirty laundry is a great social leveler. We all have it, and if we don’t deal with ours directly, someone else does. Our dirty laundry records the story of our lives. Our scent is imprinted on it. The presence of our pets decorates it. It remembers the day we spilled our coffee in the car, the morning the hot grease spattered and the nosebleed we had in bed. It gives away our cigarette habit and the acrid, sweaty smell of our secret copious alcohol consumption.

Two middle-aged women come in with stuffed pillowcases, a couple of plastic laundry baskets, a heavy green garbage bag and a couple of drawstring laundry bags, and commandeer a whole row of machines. They work well together, efficient and brisk. Obviously, they’ve done this before. They sort lights from darks, taking care to untangle and unscrunch as they load the machines. They check pockets. One of them goes from machine to machine with soap and the other with quarters. They choose hot water for the whites and warm for the colors. I wonder if they are friends, family members or from an organization like a shelter or a boarding house. Perhaps they’re church ladies dealing with donated clothes for charity. The washing machines take 39 minutes, and then the women load up a bank of dryers. As the dryers finish, they work together to fold bedding, mate socks, and put shirts on hangers. I see no children’s clothing, only adult size. One of them says to the other they’ve spent over a hundred dollars, and I wonder how often they do this. It takes them three trips to load up a battered van with all the clean clothes, and off they go.

Photo by frank cordoba on Unsplash

Dirty laundry is a cultural artifact. Back in rural Colorado, Wranglers, snap button shirts and lots of bicycling, hiking and yoga gear slosh in the machines. Here in central rural Maine everyone wears Carhartts, long underwear and thick socks. This is a blue collar community, where farmers, heavy equipment operators, sawyers and mill workers wear the same lined heavy canvas and flannel working clothes all winter.

A worn-out looking young women with a little girl comes in. Mom loads up the washer while the little girl helps by handing her things. I see no men’s clothes in this load. They sit down at a round table, the little girl with a grubby board book she found in a basket of children’s toys in the waiting area. Mom, after checking her cell phone briefly, sits idly, now and then glancing at a TV screen on the wall where a movie I’ve never seen is playing with the sound muted.

When I came to Maine, my partner had a routine. Everything went in the same machine. Socks were permanently turned inside out, because he can’t tolerate the feel of the seams against his toes. It all got OxiClean, soap and hot water. He likes things machine dried so they’re soft.

I quailed. Half of my clothes were cold water wash. I always separated colors. I much preferred to line dry.

Negotiating The Right Way To Do Laundry is one of the many hidden landmines in every living-together relationship that no one ever talks about.

Photo by Jonas Tebbe on Unsplash

Being old and wise about choosing our battles, we adjusted to one another. I stopped trying to turn his socks right-side-out. I learned to keep my cold water wash separate. I decided life was possible if I didn’t separate whites from colors and he decided clothes were still wearable if washed in warm water instead of hot. I line dry my things and machine dry his. I don’t waste time folding his clothes, because he prefers to keep them stacked neatly in a laundry basket that lives on the floor next to his side of the bed. I fold and roll my clothes, just as I always have, for my sock drawer, my underwear drawer, my tee shirt drawer and the closet shelf where my jeans live. We happily share the expense and the work.

A woman my age with a thick Maine accent and hair an improbable rich brown with no grey comes in with a load. She’s very short, and can’t reach the top of the big commercial washer to put in detergent. She goes to the counter and gets a step stool from the attendant. Her load is comparatively small and consists of a couple of violently flowered towels, jeans, shirts, socks and underwear, all looking as though they belong to her.

I love to sit and watch the contents of the washer go around through the porthole window. The gush of water, the frothy bubbles of soap and the rotating clothes give me a feeling of all’s-right-with-the-world comfort. In a crazy world, stained by so much hate, bloodshed and tragedy, here’s something within my power. I can do the laundry.

Watching the clothes whirl is like watching the inside of my head. Amongst a jumble of ideas, thoughts, feelings and memories, bits and pieces show themselves or claim my attention for seconds or minutes or hours or days, only to disappear as other colors and patterns come to the forefront of my mind. Now I catch a glimpse of my favorite pair of underwear, purple with turquoise spots. That’s like the brilliant scene, passionate and gripping, I want to write today as I work on my second book. Then a heavy brown sock shows itself, one of the pair I wore on the day I did Tai Chi in the church basement, sock-footed on the cold floor, reminding me that after this I’ll swim, and tomorrow is another Tai Chi day. White socks tumble by too quickly to tell if they’re mine (right-side-out) or my partner’s (inside-out). We need to run to the store. My partner did this chore last time. It’s my turn, but I don’t want to do it today. Tomorrow after Tai Chi? What’s on the grocery list? The sleeve of a plaid flannel shirt plasters itself momentarily against the window and is pushed away by the leg of a pair of heavy canvas Carhartts. Why are men’s Carhartt canvas pants size 32 x 30 a perfect fit, but the same size in denim is too big? The red cloth napkins we’ve been using flutter past.

The expression ‘airing your dirty laundry’ makes me smile. Oh, the shame of admitting feelings, anxieties, mistakes and less-than-perfection! Those unsightly yellow sweat stains under the arms of our shirts must be hidden from the eyes of the world at all costs, along with our humble granny panties, our favorite tattered and torn ancient tee shirt and the old towel the cat lies on. Whatever happens, we mustn’t confess the tangled smelly jumble we occasionally make out of our lives, or uncover our wounds and scars. We must never reveal neglected, malodorous piles of stained laundry in which our hope, innocence or self-esteem are buried.

Some people think admitting to dirty laundry is simply not nice. It lacks class. It’s impolite, and breaks the code of maintaining appearances at all costs. The Emperor is certainly wearing clothes, and they’re never dirty.

Photo by Bruno Nascimento on Unsplash

I challenge that. Cleansing is a sacred act of courage and wisdom. If we can’t clean out our infected wounds and cleanse our spirits, our homes and yes, our laundry, our lives won’t work well. Beating, shaking, washing and airing our laundry in the sun and fresh air is an act of healing and renewal. Allowing the world to see our dirty laundry is the beginning of cleansing and repairing, the beginning of uncreasing, unscrunching and untangling the things that disempower us. Doing laundry is a spiritual practice, a reminder that we are just like everyone else, an offering to others of our authenticity and humanity.

All content on this site ©2018

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted

by Jenny Rose | Jan 18, 2018 | Connection & Community, Emotional Intelligence

For several weeks the depth of snow has limited my ability to walk on our 26 acres. Last week we had a couple of inches of rain that arrived with the scent of the sea and tropical warmth, followed by a hard, fast freeze. The rain melted a great deal of snow and we had flooding. The sudden freeze created a hard crust on the remaining few inches of snow, and as we returned to subzero winter temperatures I decided to see if I could get down to the river.

Photo by Vincent Foret on Unsplash

The crust supported my weight — sometimes! Other times I broke through and floundered up to my knees, the icy rind bruising and scraping my lower legs in spite of long underwear and heavy canvas pants. I saw tracks of deer and moose, rodents and birds in the snow. The river, ice encased, had thawed slightly and flooded during the rain, so the cracked ice was piled in slabs. In some fissures I could see open water. In other places thin new ice had formed and old, yellow ice lay flat but spiderwebbed with cracks.

As I stood next to the river catching my breath and marveling at the power of winter, I could hear the voice of the ice. It’s an odd sound, because it comes from beneath one’s feet rather than the sky or the world around. The ice pops and groans, sings and mutters and snaps. It’s a wild, unearthly voice, a chorus of cold water, cold air and cold crystals, the medley of flowing, living water and rigid winter armor. I wondered what it sounded like to the creatures hibernating in the river bed and the beavers in their dens.

The trees here have voices as well. When the wind blows they creak and groan as they sway, and their branches rub together, making a classic haunted house rusty hinges sound. In the deep winter when it’s very cold, sap freezes, expanding, and the trees explode with a sound like a gun going off. Sometimes they split right through the trunk.

So many voices in this world. Every place has its own special choir, every season its own song. The sound of a beetle chewing bark, the Barred owls calling to each other in the snow-bound January night, the agonized shriek of a vixen calling for a mate on a February midnight of crystal and moon, and the barely discernible high-pitched talk of the bats as they leave their roost at dusk are all familiar voices to me.

I’m a seeker of voice, a listener, partly because I’m a writer and partly because I know what it is to be silenced. Our world contains so much pain and suffering, such unimaginable horror and injustice that my compassion is frequently overwhelmed. I cannot staunch the wounds and wipe the tears of the world.

But I can listen. I can bear witness. I can stand and wonder and marvel at the wild ice, the mating owls, the hunting bats and also the handful of people in my life. For a few minutes, I can encircle another with my presence and attention, allowing their voice to speak freely, truly and fully. I can choose to have no agenda about the voices of others, no expectations or judgements.

I can also give that to myself. It’s only in the last three or four years that I’ve reclaimed my own voice. That, more than anything, is why I began writing this blog. Once a week I sit in front of a blank page and write in my true voice. Blogging, for me, is not about validation or statistics. It’s not about trying to please anyone, creating click bait or competing. It’s about contributing my voice because I am also here, not more important but as important as anyone else.

Using our voice does not require a listener.

Listening to the ice and the world around me has allowed me to realize, for the first time, how deeply I’m committed to appreciating and supporting authentic voice. My appreciation is a thing apart from agreement or disagreement with what I hear. Speaking our truth is not a matter for criticism. It’s an offering of self, and listening without judgement is an acceptance of that offering. I feel no need to annihilate those I disagree with.

Photo by Quino Al on Unsplash

The dark side of voice is the voice that deliberately drowns everyone else out, the voice that silences, controls and distorts our world and our sense of self. The voice that deliberately destroys is an evil thing, a thing afraid and threatened by the power of others. Dark voices throw words like a handful of gravel in our faces.

An essential part of self-care is learning to recognize, minimize and/or eliminate our exposure to voices we experience as destructive or silencing. This is boundary work. Note the difference between appropriate boundaries and dropping an atomic warhead. Healthy boundaries do not disrespect, invalidate or silence others.

I wonder what the world would be like if all criticism, jeering and contempt were replaced with “I hear you. I’m listening. I believe in the truth of your experience. You are not alone.” What would we be like if we gave that gift to ourselves?

Photo by Quino Al on Unsplash

And what of lost voices? I don’t mean unheard or unremarked, but those voices who spoke, faintly, for a moment, and then were silenced so brutally and completely no one but the silencer heard their last cry. Such a person lives, breathes, walks, eats and sleeps, but he or she is a shell mouthing superficial words. Attempts to draw close, to understand, to share authentically and elicit a true voice in return are all in vain. The phone is off the hook. Silence and deflection are the only response. No one is at home. Love and listening count for nothing and behind the mask is only emptiness. Connection is denied.

How many voices can we truly hear? The world is filled with a cacophony of sound made by billions of people. Even here in the heart of Maine the voice of the river is punctuated by traffic noise. We all seem intent on increasing our exposure to voices via social media, 100 TV channels, streaming, downloading and YouTube. Does all this clamor make us better at listening and honoring voices? Can we listen to our child, our mate, the TV, and read Facebook all at the same time?

Some people say they can, and perhaps it’s true. What I know is I can’t. I don’t want to. I don’t feel listened to when I’m competing with other voices. I can’t hear myself when my day is filled with racket and din. I can’t extend the gift of presence to 100 friends on Facebook. I can’t discern between an authentic voice and a dark voice in the middle of uproar.

Voice is precious. It’s sacred. No created character lives in our imagination without voice. Silencing voice is a horrific violation. I have promised myself I’ll never again abdicate my own voice.

Honoring voice, yours, mine, theirs, and the world’s.

All content on this site ©2018

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted

by Jenny Rose | Jan 11, 2018 | Connection & Community, Emotional Intelligence

In life coaching, I was introduced to the idea that human beings have three primary needs: Connection, contribution and authenticity. I have yet to discover a need that doesn’t fall into one of these categories, so at this point it’s still a frame that works for me.

Photo by Peter Hershey on Unsplash

For me, any discussion of connection must include spiritual connection, and to talk about that clearly I need to define terms.

Spirit: The nonphysical part of a person that is the seat of emotions and character; the soul.

Religion: The belief in and worship of a superhuman controlling power, especially a personal God or gods.

Faith: Strong belief in God or in the doctrines of a religion, based on spiritual apprehension rather than proof.

Ideology: The ideas and manner of thinking characteristic of a group, social class, or individual.

Sacred: Connected with God (or the gods) or dedicated to a religious purpose and so deserving veneration.

(All definitions from Bing search.)

Spirituality: Spirituality may refer to almost any kind of meaningful activity, especially a “search for the sacred.” It may also refer to personal growth, blissful experience, or an encounter with one’s own “inner dimension.” (Wikipedia)

The archeological record tells us we have sought to understand ourselves as part of a greater whole from the infancy of mankind. Long before written records were made, there was cave art, pottery and carving thought to represent sacred beings, including, in many cases, animals. When we began to write, myth, story and legend wove a rich tapestry of religion and other spiritual frameworks all over the world.

Our powerful need for spiritual connection has historically been a significant motivator geopolitically, economically and creatively. Our search for understanding who we are and what our place in life is, individually, culturally, politically and socially, firmly anchored in our conception of spirit.

How do we create a spiritual connection? How do we choose from such a bewildering array of beliefs and ideologies? How do we cope with tribal shaming if we don’t accept the spiritual beliefs of our family or tribe? How do we think about the “nonphysical part” of ourselves, and what, if anything, does that part of us need?

It’s taken me more than 50 years to even begin to answer these questions. The two biggest obstacles I had to overcome were disconnection from my own feelings, and denying having any needs. Disconnection and denial are both disempowering, and healthy spiritual practice, at its heart, is a practice of self-empowerment.

Some people approach formal, organized religion as a way to share power. Others are quick to use it to assure power over others, and at that point it no longer fits my definition of a healthy spiritual practice. Discovering and nurturing the shape of our own spirit is an act of dignity, privacy and self-respect. It has nothing to do with what anyone else thinks or believes. We decide where we stand on the continuum between science and faith, and we define what is sacred in our lives. We have the power, and we have the responsibility. No mystic, guru, psychic, yogi, mentor, sponsor or other spiritual or religious leader or authority knows what we need better than we do. We owe nobody an explanation, justification or apology for our spiritual practice, as long as that practice doesn’t seek to harm or control others.

That’s not to say the guidance, teachings and wisdom of scholars, practitioners, philosophers, masters and thinkers are without value or interest. Yoga, martial arts, meditation, mandalas, drumming, dance, sacred traditional music and countless other rituals and traditions may be part of a spiritual practice, but none of these are essential. The real strength of spiritual practice doesn’t lie in appearance, embellishments, publicity or visibility and has nothing to do with economic or social condition.

A spiritual practice is an activity in which we are wholly present with ourselves in a nonjudgmental fashion and after which we feel empowered, anchored, refreshed and renewed. A healthy spiritual practice is a haven, a refuge, a place of solace and joy. It connects us to ourselves, to others, and to something larger than we are. It doesn’t matter if we name that something God, Allah, Spirit, Divine, Goddess or even Gaia, it all boils down to the basic human need for some kind of spiritual connection.

A few weeks ago I wrote about living a seamless life. My spiritual practices are frequently invisibly embedded throughout my every day life, requiring nothing more than my presence and intention.

Here’s an example: After a long day the kitchen is full of dirty dishes. I slather my hands with the most luxurious lotion/cream in the house and don rubber gloves. I turn off lights, tech and the TV. I light a couple of candles. I might play some music, or just soak up silence. I look out the window over the sink. I breathe. I relax. I’m present. I’m consciously grateful for a kitchen, dishes, a sink, running hot water, the ability to stand and use my hands, and food that creates dirty dishes. I take time to feel what I feel, check in with myself, daydream and drift.

I approach exercise as a spiritual practice. I’m not worried about my weight or health, but I do notice I feel better, sleep better and function better if I stay active, so my daily goal is to show up at some point with myself to move. Sometimes I dance. Once a week I swim, then soak in a therapy pool, then take a long hot shower. I walk, both by myself and with my partner. This winter I’m going to begin snowshoeing. I do Tai Chi. With the exception of walking with my partner, all of these activities are opportunities to have time with myself, quiet, undistracted time in which to be in my body, remember what a beautiful world I live in, practice gratitude, allow feelings, pray, chant, sing, work creatively, stretch and breathe. When I’m finished I feel relaxed, empowered, centered and grounded.

Photo by Miranda Wipperfurth on Unsplash

A spiritual practice may be as simple as a special tree, rock, crystal, cushion and/or candle. It might be a secret altar or shrine, a string of beads or a stick of incense. It can take place anytime, anywhere, solo or in a group. It can be a five-minute pause or a long weekend of ritual at a hot spring, but it always makes us bigger. Anything that diminishes, restricts, confines, limits, shames, invalidates or disempowers us is not a healthy spiritual practice, no matter what anyone says. It’s merely an ideology of control.

Many of us naturally find our way into spiritual practice without realizing what we’re doing, impelled by this often unconscious but powerful human need. Recognizing the need for spiritual connection, giving it language, honoring and allowing it, allows us to take back our power to define and protect sacred space in our lives, free from distraction, interruption, multitasking, pressure, hurry and the constant noisy static of media and entertainment. If our spiritual life is tainted by criticism and judgement, our own or others’, it won’t sustain us and our spirit will sicken and starve. We’ll begin to look outside ourselves for spiritual nourishment and become vulnerable to addiction, perfectionism, pleasing others and people who steal power.

The care and feeding of the spirit is the least talked about aspect of the need for connection, but it may be the most important. In the absence of spiritual connection, all our other connections suffer. True spiritual power transcends physical strength, youth and beauty, and it cannot be coerced or stolen. Our greatest strength may lie in our ability to create spiritual connection for ourselves and support others in theirs.

Photo by Deniz Altindas on Unsplash

All content on this site ©2018

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted

by Jenny Rose | Dec 28, 2017 | Connection & Community, Emotional Intelligence

Character: The mental and moral qualities distinctive to an individual; a person in a novel, play or movie.

Photo by Nick Grappone on Unsplash

I’m fascinated with the places between. All the places between. Threshold places. Edge-of-chaos places. Here-there-be-dragons places off the edges of maps. It’s in the gaps, fissures, cracks and edges that I mine for the characters that inhabit my writing. It’s in the between places my own character is shaped, and I gain the clearest understanding of the characters around me.

I’ve written about labels before. Discovering characters is not about labels. Labels aren’t people. We’ve had a lot of reminders recently that talent, success, money and power fail to fully define character. Ours is a culture of texts and tweets, acronyms and jargon like “neoliberal” and “postmodernism.” We’ve become skilled at reducing ourselves and others to one-dimensional paper dolls with the application of a label. It’s an all-or-nothing kind of culture. We’ve no time or interest to invest in understanding complexity.

But what lies between the enormously talented actor and his serial sexually abusive behavior? What is the untold story of the “perfect” mother who drives into a lake with her kids in an act of murder and self-destruction? How do we think about the extraordinarily gifted writer who is also homophobic, or a child abuser? Who are we in the gap between what we believe ourselves to be, what we define ourselves to be, what we want ourselves to be, what we’re afraid we are, and how we actually show up in the world in the experience of others?

In that space between lies real character. That’s where I’m at work, listening, taking notes, asking questions and observing. As a writer, I must know my characters. What are they afraid of? What’s their worst memory? What’s their ideal vacation? What motivates them? What does their sock drawer look like? What’s in their car? What’s on their desk? How do they treat a service person? How many unopened emails squat in their inbox? Where do they want to be in five years? In ten years?

Defining ourselves or others by a single characteristic, choice or ideology doesn’t build connection, understanding or empathy. We can spend hours online, commenting, facebooking, blogging and interacting with others about every issue from sexual politics to diet, but none of it defines our character as honestly as how we treat a real live co-worker who identifies as transgender, or what kind of food we actually have in our refrigerator.

Those tantalizing, fertile, often concealed places between! Interestingly, words obscure the places between. Words are capable of seductive lies, but action, especially action taken in the stress of an unexpected moment, points unfailingly to true character.

Another problem with labels is their inflexibility. We each perform hundreds and hundreds of actions a day, and some are notable for how well they don’t work out. Labels imply we don’t change, we don’t grow, we don’t adapt and adjust and learn, when in fact the opposite is true.

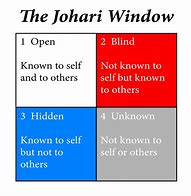

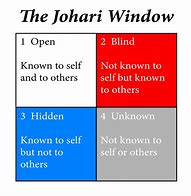

The Johari Window is a concept created by a couple of psychologists in the 1950s to help people understand their relationships with themselves and others. The window suggests that we cannot see ourselves or others entirely; there is always a space of possibility to discover. Fully defining character becomes a community project. Even so, the unknown or hidden parts of character can and do appear suddenly and overwhelmingly, often resulting in some kind of heinous act and leaving us struggling with what we missed, what we didn’t know or what we didn’t want to admit.

The Johari Window is a concept created by a couple of psychologists in the 1950s to help people understand their relationships with themselves and others. The window suggests that we cannot see ourselves or others entirely; there is always a space of possibility to discover. Fully defining character becomes a community project. Even so, the unknown or hidden parts of character can and do appear suddenly and overwhelmingly, often resulting in some kind of heinous act and leaving us struggling with what we missed, what we didn’t know or what we didn’t want to admit.

It’s so fatally easy to misunderstand and underestimate others, especially when we can’t observe, talk and interact face-to-face with someone and compare their actions with their words over the long term. Complexity takes time. Making judgements based on labels does not.

As a writer, I’ve learned to look at myself and others with a more interested and less judgmental eye. I’ve learned to set up camp in the places between, look and listen carefully, observe keenly and ask a lot of questions. I’ve concluded that people who toss labels around are often in too much of a hurry to achieve power over others and silence challenge or dissent to engage in thoughtful dialog or discussion. Label users reveal far more about themselves than whoever they’re labeling. It’s a diversionary tactic.

Who is that character hiding behind all the labels they’re slinging left, right and center? What’s really going on with them? What kind of fear, uncertainty, insecurity, pain or lust for power motivates them? Who taught them to use labels so carelessly and unhelpfully? What needs are they trying to meet?

Photo by Quino Al on Unsplash

An engaging character is one who defies labels, one who challenges preconceptions, one we empathize with and even care about in spite of the abhorrent choices they make. A well-written character is complex and dynamic.

This week is one of those between places. We’re swinging between Christmas and the New Year, between 2017 and 2018. The holiday season has stirred up our memories, our family situations, our grief, gratitude, and financial fears. We’ve traveled, abandoned our usual diet and routines, gotten worn out and indulged in sugar and alcohol. The flu is abroad. The package was stolen off the porch. The dog bit Santa when he came down the chimney.

Here, my friends, is the between place of authentic character. Not who we wish to be. Not who we say we are. Not who we present ourselves as on Facebook or pretend to be for our families and coworkers or resolve to become in the New Year, but who we are today, with our blind spots, our secrets, our fears, our greasy oven, our favorite coffee cup, indigestion, bills to pay, snow to shovel, our comfy sagging chair and what we choose to do with this in-between time.

Powerful characters. May we create them. May we discover, foster and celebrate them in others. May we honor our own.

All content on this site ©2017

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted