by Jenny Rose | Jun 24, 2023 | Connection & Community, Emotional Intelligence

My work team and I provide services to patients and the public in our aquatic rehab facility in Central Maine, which means it’s impossible for me to live in a bubble. Thank goodness.

I’ve been complimented, praised, flirted with, yelled at, accused, and blamed. I’ve listened to a wide range of political and religious viewpoints with a polite face on. I’ve dealt with tears and tantrums (not talking only about the kids here). I’ve heard about medical and family history in excruciating detail, often repeatedly. I’ve watched patrons and patients get better, and I’ve watched them get worse. I’ve watched them lose weight and gain weight. I’ve met grandchildren and siblings when they visit Maine. I interact with people who are confused, struggle with memory loss, or are affected by dementia, either their own or a loved one’s.

I’ve seen a variety of sexual identities, gender presentations, and body dysmorphia (and no, I’m not conflating body dysmorphia with homosexuality.) My team has served patrons who are listed on our state sex offender registry.

We serve deaf patrons, autistic patrons, anxious patrons, mentally ill patrons, special needs patrons of all kinds and ages. We serve an occasional minor who gets dumped in our emergency room and lives there for a time while the authorities try to find placement.

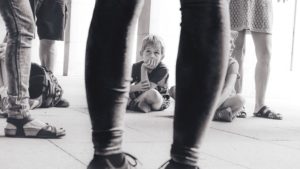

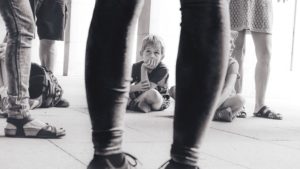

Image by Bob Dmyt from Pixabay

People. All kinds of people. All colors, shapes, ages, and sizes. All different.

People just like me.

I notice a thing in the present cultural discourse. People who browbeat others about inclusion and tolerance invariably are the least inclusive and tolerant.

Talk (and typing) is cheaper every day.

As a writer and lover of words, I notice a deluge of new terminology and labels, many of which strike me as ridiculous, redundant, and/or meaningless. Their sole purpose appears to be to increase the ways we can despise and exclude one another. At the same time, there’s an ominous drumbeat in the background about ideas and words some person might find offensive and therefore must be forcibly eradicated. A few months ago one of my adult sons said to me, “Mom, you can’t use the word science in public,” as though explaining socially acceptable language to a child. All I could do was look at him in disbelief.

Science is not a dirty word. Disagreement is not hate, and respect and tolerance do not equal agreement. Asking questions is not a call to arms.

The Word Police are out in force, trolling online and hijacking us in public places. Virtue signaling has begun to take the place of authentic discourse. We’re harshly and instantly judged and labeled by the language we use and the ideas we express.

Toni Morrison said, “Definitions belong to the definers, not the defined.” I think about that every day. Another phrase frequently in my mind is “I’m okay with your disapproval of me.” People have been disapproving of me since the day I was born. I’m used to it. The sky hasn’t fallen yet and somehow I manage to continue to exist.

I’m not the slightest bit interested in disapproval, labels, or sweeping generalizations, which are increasingly idiotic as labels proliferate.

I’ve been reading lately about the “tribe of one,” the logical endpoint to the cultural mandate to divide ourselves into ever-decreasing groups until we’re each completely isolated, believing no one can possibly understand our particular experience as a self-defined ______, _____, etc. Therefore, the world is against us, we’re marginalized and oppressed victims, and we’re owed power, respect, and tolerance no matter how egregious our behavior is. No one is included in our little bubble. Everyone is excluded. Yet we expect and demand inclusion, which is to say, accommodation.

Who benefits from this solipsistic isolation? Is this the kind of human experience we want for ourselves, for our children? Is this social justice?

There are other paths to take. We could focus on our similarities, on the common human experiences binding us all together. We could build a new lexicon of connection rather than division. We could stop using labels, even in the privacy of our own heads. We could value curiosity more highly than outrage, confidence more than a constant state of offense. We could value authentic expression more than virtue signaling.

We seem to have forgotten the real world is not a set of disconnected bubbles. An infinite number of labels (including pronouns) cannot describe the entirety of a human being. Experiences define human beings. Birth. Death. Connection. Feelings. Living in a body. These bind us together. The life we are living defines us, not labels.

Every single one of us in this moment is included in the human family. We all have that in common. Why are we so determined to slash that root into pieces? I ask again, who benefits from this brutal severing? Why are we participating in it? How have intelligent, well-meaning, compassionate people become machete-wielding destroyers, all the while mouthing words like ‘inclusion’ and debating pronouns?

At work (and elsewhere), I’m focused on people. Of course I notice skin color, sometimes eye color, hair, body type, spoken language, cognitive and physical ability. I also notice tattoos, scars, stretch marks, skin tags, moles, and the occasional blood-bloated tick! Swimming suits are revealing clothing. None of these details define anyone, however. For me, they’re value neutral. I don’t connect or disconnect because of someone’s appearance. I can’t make valid generalizations about anyone based on the way they look. We treat everyone who comes in the door with the same respect; our expectations in terms of adhering to our safety rules are the same for everyone. We accommodate differing physical abilities and needs without fuss.

Wheelchairs, walkers, prostheses, oxygen, health status and injury are details, not definitions.

Now and then I interact with someone I hardly know who makes it plain they disapprove of something I said, or wrote, or chose. They were triggered. They were outraged. They were offended. I’m met with a curled lip, judgement, and criticism. I’m made to understand I’m hateful and bigoted, which I don’t take too seriously, as I’m neither. Anyone who knows me at all knows that.

By Landsil on Unsplash

In short, I’m immediately excluded, and there is no court of appeals. There’s no mutual bridge-building. Because of a word or an expressed point of view I’m entirely rejected, now and forevermore. Most of the time I consider the source and shrug off this kind of interaction. In certain circumstances, however, it’s destructive and hurtful in a more personal way. We can’t always choose the people in our lives. I can’t build connections alone.

Situations like this invariably catch me off guard. When someone expresses a view or belief I disagree with, I simply step around it. I change the subject, probing for connection points. I don’t concentrate on our differences or potential disagreements. I don’t expect others to fall in line with my beliefs. I don’t shame or shun others because they have a different point of view. I don’t think of myself as being on higher moral ground, and when others come at me with moral indignation, it makes me smile inwardly. Good grief! Get over yourself already.

I’m willing to include you. Will you include me? I ‘ll give you tolerance and respect. Will you give them to me? I’ll give you the benefit of the doubt. Will you give it to me?

I’d rather be curious than outraged. I’d rather have confidence in myself and my experience than maintain a hair trigger on my sense of offence. Most people don’t mean to be offensive. If they do, it’s best to ignore it. Life is too short to spend my days in a constant state of outrage and offense. It doesn’t change anything and nobody cares. Cultivating a sense of humor is more fun.

We’re not entitled to have our triggers, sensitivities, and ideology accommodated.

If we’re all especially vulnerable, broken, or traumatized, none of us are. If we’re all oppressed victims, none of us are. If we’re all vile haters and bigots, none of us are.

What we all are is … human beings. As human beings, not a single soul is excluded. Isn’t it enough to simply be the best human beings we can be and allow those around us to do the same?

Questions:

- When you think of a person in your life, do you think of a list of labels or do you think of a human being? Once someone is labeled, do you ever feel you’ve mislabeled, misunderstood, or misjudged them? If so, do you admit it and eradicate the label?

- Can you describe someone you know without using a single label? Try it!

- In the first five minutes of contact with a stranger, are you seeking to build connection or mentally applying labels to them? Which labels do you check for first?

- Do you turn away from anyone who disagrees with or questions your particular ideology or belief system? Do you view such people as hateful? Is it possible to disagree with you or question you and still be a good person?

Leave a comment below!

To read my fiction, serially published free every week, go here:

by Jenny Rose | Aug 27, 2022 | Connection & Community, Emotional Intelligence

A little over three years ago I wrote a post titled “Questions Before Engagement.”

Since then, the world has changed, and so have I.

I’m not on social media, but my biggest writing cheerleader is, and he tells me people are talking about how to recognize red flags. He suggested I post again about problematic behavior patterns.

A red flag is a warning sign indicating we need to pay attention. It doesn’t necessarily mean all is lost, or we’ve made a terrible mistake, or it’s time to run. It might be whoever we’re dealing with is simply having a bad day. Nobody’s perfect.

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

A persistent pattern of red flags is significant. Ignoring problematic behavior sets us up to get hurt.

The problem with managing red flags is we may be flying several ourselves, and until we figure out our own behavior we’re going to struggle to deal effectively with others.

We all have an excellent built-in system alerting us to possible danger. We call it intuition, going with our gut, or having a hunch or a feeling. We may not know why we feel uneasy, but we subconsciously pick up on threatening or “off” behavior from others. The difficulty is we’re frequently actively taught to disregard our gut feelings, especially as women. We’re being dramatic, or hysterical, or a bitch. We’re drawing attention to ourselves, or making a scene. What we saw, heard or felt wasn’t real. It didn’t happen, or if it did happen, we brought it on ourselves.

We live in a culture that’s increasingly invalidating. Having a bad feeling about someone is framed as being hateful, engaging in profiling, or being exclusive rather than inclusive. Social pressure makes it hard to speak up when we feel uncomfortable. Many of the most influential among us believe their money and power place them above the law, and this appears to be true in some cases. In the absence of justice, we become apathetic. What’s the point of responding to our intuition and trying to keep our connections clean and healthy when we can’t get any support in doing so?

If we grow up being told we can’t trust our own feelings and perceptions, we’re dangerously handicapped; we don’t respond to our intuition because we don’t trust it. We talk ourselves out of self-defense. We recognize red flags on some level, but we don’t trust ourselves enough to respond appropriately. Indeed, some of us have been severely punished for responding appropriately, so we’ve learned to normalize and accept inappropriate behavior.

So before we concern ourselves with others’ behavior, we need to do some self-assessment:

- Do we trust ourselves?

- Do we respond to our intuition?

- Do we choose to defend ourselves?

- Do we have healthy personal boundaries?

- Do we keep our word to ourselves?

- Do we know how to say both yes and no?

- Do we know what our needs are?

- Are we willing to look at our situation and relationships clearly and honestly, no matter how unwelcome the truth might be?

Photo by freestocks.org on Unsplash

Once we’ve become familiar with our own motivation and behavior patterns, we can turn our attention outward and focus on the behavior of those we interact with.

Red flags frequently seem too bad to be true. In intimate relationships with partners and family, the anguish of acknowledging toxic or dangerous behavior and setting limits around it cannot be overstated. Those we are closest to trigger our deepest and most volatile passions. This is why it’s so important to be honest with ourselves.

The widest lens through which to examine any given relationship is that of power-over or power-with. I say ‘lens’ because we must look and see, not listen for what we want to hear. Talk is cheap. People lie. Observation over time tells us more than words ever could. In the case of a stranger offering unwanted help with groceries, we don’t have an opportunity to observe over time, but we can say a clear “no” and immediately notice if our no is respected or ignored. We may have no more than a minute or two to decide to take evasive or defensive action.

If we are not in an emergency situation, or dealing with a family member or person we’ve known for a long time, it might be easier to discern if they’re generally working for power-with or power-over. However, many folks are quite adept at using the right words and hiding their true agenda. Their actions over time will invariably clarify the truth.

Power-over versus power-with is a simple way to examine behavior. No labels and jargon involved. No politics. No concern with age, race, ethnicity, biological sex, or gender expression. Each position of power is identifiable by a cluster of behaviors along a continuum. We decide how far we are willing to slide in one direction or another.

Power-Over

- Silencing, deplatforming, threatening, personal attacks, forced teaming, bullying, controlling

- Win and be right at all costs

- Gaslighting, projection, DARVO tactics (Deny, Attack, Reverse Victim and Offender)

- Fostering confusion, distrust, disinformation, and violence

- Dishonesty

- Poor communication and refusing to answer questions

- Emotional unavailability

- High-conflict behavior

- Blaming and shaming of others

- Refusal to respect boundaries

- Inconsistent

- Refusal to discuss, debate, learn new information, take no for an answer

- Lack of reciprocity

- Lack of interest in the needs and experiences of others

Power-With

- Encouraging questions, feedback, open discussion, new information, ongoing learning, critical thinking

- Prioritizing connection, collaboration, and cooperation over winning and being right; tolerance

- Clear, consistent, honest communication

- Fostering clarity, trust, information (facts), healthy boundaries, reciprocity, authenticity, and peaceful problem solving

- Emotionally available and intelligent

- Taking responsibility for choices and consequences

- Words and actions are consistent over time

- Respect and empathy for others

We don’t need to be in the dark about red flags. Here are some highly recommended resources:

- The Gift of Fear by Gavin de Becker

- Bill Eddy’s website and books about high-conflict personalities

- Controlling People by Patricia Evans

Image by Bob Dmyt from Pixabay

by Jenny Rose | Jul 23, 2022 | Aging, Connection & Community, Emotional Intelligence

As I serial publish my Webbd Wheel series on Substack, I’m discovering some kindred spirits on the platform. Keri Mangis writes a newsletter called The Power Source, and she recently wrote a piece about being an outsider that caught my eye.

Photo by Joshua Rawson-Harris on Unsplash

I’ve written about the longing to belong previously. The desire to feel firmly anchored in family and community is an ache I’ve felt most of my life. Though I’ve belonged a few precious times in my life and I know what it feels like, I know more about what it doesn’t feel like.

Mangis suggests being an outsider is powerful because being an insider is so much work. We trim and prune and espalier ourselves to stay safe in our feeling of belonging. Humans are social animals. We’re neurobiologically wired to fear being outcast and alone.

Childhood is about learning roles, rules, familial and cultural norms, and, for most of us, under which specific conditions we can be loved and accepted and achieve belonging. Unconditional love is not our best thing.

By the time we’re young adults, we know what’s expected of us if we want to belong. The parts of us that don’t fit in are amputated or hidden, and we often live a double life, one secret and one playing to our audience, or we make ourselves into masks and shells, acceptable to our peers, families, and communities, but lacking authenticity or vitality.

Either choice is a lot of work. Making yourself small is exhausting. Ask any woman.

What we really want is for our real selves to belong, our honest, authentic selves, but few of us are lucky enough to find that easily, and the fear of being alone is huge.

We have a tendency to think of maturity as taking place in the first 20 years of life. By then we’re in our adult bodies and generally able to function on our own. We define ourselves as grownups, adults. We take on responsibilities, pursue education and interests, figure out the economics of independence. Some people form partner bonds and raise children. We’re busy in the world and much of that busyness has to do with belonging, taking care of social obligations, participating in production and consumption, and bumping up against limitations, rules, and taboos. We use our manners, follow traffic rules (sometimes), stand in lines, allow ourselves to be directed by signs, and generally follow the same standards of civility we learned in school.

We also subscribe to ideologies and resist change in the form of new information or critical thinking. We can’t endanger our places of belonging. Our identity depends on them.

Photo by Cristina Gottardi on Unsplash

In exchange, we are paid for our work, have friends, family, and community, wear our labels comfortably, and stay safe in the middle of the herd.

Then suddenly we’re old, negligible, invisible, and burdensome.

Then we die.

But what if the first 20 years are just the beginning? What if, as Mangis suggests, we embark on a new level of maturity in late middle age? What if that level requires we outgrow the need to belong and leave the longing for it behind?

I know from my study of power dynamics fear-driven choices indicate power loss. The fear of being outcast and alone is terrible, and so is the fact of it.

However, it is survivable, and it’s also a much, much easier way to live. The degree to which we’ve spent our first 50 years or so living underground or in the shadows is the degree to which our lives simplify if we decide belonging isn’t so important after all.

Suddenly, we can be as big, as expansive, as individual, as happy, as creative, as expressive, and as strong as we choose. We’ve spent 50 years learning about ourselves and the world. We’re no longer overwhelmed with the physiological needs of reproduction. If we give up our fears and struggles around belonging, what could we do with that energy? Belonging is expensive, and so is longing.

Perhaps mid-life crises are really just another growth spurt, a milestone to be celebrated and welcomed.

Instead of framing these years as the beginning of the end, perhaps we could look at them as the beginning of our most authentic years, the years in which we’re less concerned about how acceptable others find us, stop apologizing for who we are, and focus on reclaiming ourselves and belonging in our own skins.

At the end of the day, we belong only to ourselves. We’re not required to give up our power for transformation in order to belong to anyone else.

All we have to do is let go of our longing for belonging.

Photo by Mike Wilson on Unsplash

by Jenny Rose | Jan 22, 2022 | A Flourishing Woman, Creativity

One of my greatest unconscious defaults in life is avoidance. I know now, thanks to Peter Walker and his work, avoidance is a natural trauma response.

Nothing makes me crazier than people who avoid unpleasant things.

Photo by Ian Espinosa on Unsplash

Is there a pattern here? (Laughter in the wings.)

I’m thinking about this because I’m steadily publishing my fiction in serial form on Substack, week by week, about 10 pages by 10 pages, and it’s a challenge.

Something in me wants to avoid revealing my own creativity. My writing takes me to some dark, and some people would say inappropriate, places. Every week (I just posted for the 8th week), I push myself through whatever the content of my post happens to be. More than that, I deliberately take it on in an accompanying essay.

I’m an expert in self-sabotage. I’ve been doing it my whole life, largely through simple avoidance. At the same time, it appears my previously intermittent and now increasing tendency to call a spade a spade and be honest about my experience is one of the characteristics others struggle with most when they deal with me.

It’s a strange paradox, and it creates ongoing internal tension.

The avoidant part of me is childish and disempowered. The direct, take-the-bull-by-the-horns part of me is powerful and hangs out with Baba Yaga.

I love the direct part of myself, but I don’t think anyone else can. I think others want the avoidant woman, because she’s so damn “nice.”

Ick.

When I first began writing creatively, I thought it would all be sweetness and light, love and romance, happily ever after.

Photo by Peter Forster on Unsplash

As the years passed, and I expanded out of (mostly bad) poetry, played with writing oral stories, and then started seriously writing fiction, my output took a darker turn. The sweetness and light included bitter and dark. The love and romance became raw sensuality and included detailed sexual content. I took old fairy tales, cleansed by the brothers Grimm and others, and excavated the darker, dirtier, more violent roots. My characters graphically tore out eyes and watched them change into marbles. They killed people. They ate people. Shapeshifters had sex. Towers fell. People went to war and practiced genocide.

My writing wasn’t dark on every page, but it wasn’t sweetness and light on every page, either. It made me cry. It made me cringe. It made me uncomfortable because of its emotional power. I wondered at myself. Yet never have I been so captured, so challenged, so confident, so happy as I am when writing.

After all, in those days almost nobody read it! I wrote for myself, and held nothing back.

Now I’ve deliberately changed that. Now anyone can read it. And some people are.

For a while I considered cutting the parts I judged as being too … what? Too honest? Too sexy? Too potentially offensive? Too violent? Too real?

Yes. All those things.

My impulse was to avoid revealing myself. Stay safely hidden. Stay small. Refrain from making myself or anyone else uncomfortable.

Even as I considered that, I knew I wouldn’t. I knew I couldn’t betray myself that way. If I’m to be judged as not good enough, I want the judgement based on the deepest, most complex, most powerful and honest work I’m capable of.

Because that’s the only way my writing is good enough for me.

My Substack post last week included explicit sexual content. There will be more, but that was the first. I wrote an essay to go with it titled “Creating the Webbd Wheel: Sex.” I’ve been worrying about that post for weeks. In the end, I kept it simple and direct. I was writing about sexual content. The title was clear. Why prevaricate?

Substack provides writers with statistics 24 hours after they post, and I was informed my essay got the most reads of anything I’ve posted so far.

I’ve been giggling ever since. So far, nobody’s given me a bad time about my sexual content, but even if they do, I know I was right in what I wrote in that essay. Nobody wants to talk about sex, and we all have a lot of judgement and fear around it, but that doesn’t mean it occupies none of our private attention. We can’t amputate ourselves from our sexual nature, no matter how much we wish we could or others tell us we should.

I will probably unconsciously default to avoidance for the rest of my life. It’s a deeply-rooted pattern. I’m socially rewarded for being “nice.” On the other hand, I personally value authenticity and honesty far more than I do niceness. I want to grow up to be direct and clear. Not mean, but not avoidant or arguing with what is, either. It’s a fine line, one I don’t walk steadily or gracefully.

But I’m not going to avoid the attempt.

Photo by Jon Flobrant on Unsplash

by Jenny Rose | Nov 7, 2021 | A Flourishing Woman, The Journey

A frequent conversation among my coworkers at our rehab pool facility, as well as our mostly middle-aged and older patrons and patients, has to do with the unexpected places life takes us. How did we get here from there?

Photo by yatharth roy vibhakar on Unsplash

For some this is a bittersweet question, for others an amusing one, and for others a bewildered or even despairing one. Whatever our current reality is, none of us could have foreseen or imagined it when we were young adults.

We can all talk about dreams we’ve had, intentions, hopes, and choices we’ve made in pursuit of the life we imagined we wanted, but life itself is always a wild card. It picks us up by the scruff of our neck, sweeps us away, and casts us onto strange shores.

As I age and practice minimalism, I realize keeping my dreams flexible has never been more important. My dreams, along with everything else, change. What I longed for as a young woman is not what I want now. What I needed in midlife is not what I want as I approach my 60s. Some things I’ve thought of as merely desirable are now essential, and other things I thought I needed no longer seem important.

In some ways I like dancing with change, my own as well as external circumstances. It feels dynamic and healthy. Resilience and adaptation are strong life skills.

In other ways it’s hard, the way my needs and I change. Often, I feel my own natural change and growth are hurtful to others. I try to hold them back. I try to stop myself, make myself quiet and small so no one will be upset, including me!

In the end, though, there’s something in me that’s wild, and sure, and deeply rooted in the rightness of change. It can’t be silenced or stifled, and there’s no peace for me until I begin living true to myself once again, no matter the cost.

The costs are very high. The personal costs of living authentically have been catastrophic for me. Sometimes I feel I’ve paid with everything I ever valued.

And yet the power of living authentically, the peace of it, the satisfaction of shaping a life that really works and makes me happy … How much is too much to sacrifice for that?

For a long time, I’ve thought about balance. Financial balance. Work-life balance, which is a term so nonspecific as to be useless. Balancing time. Balancing socialization and solitude. Balancing sitting and writing with physical activity. The complex balance of give and take in relationships. Balancing needs and power.

Minimalism is about balance. Achieving a simple life demands balance, something hard to find in an overcrowded life. Practicing simplicity and working toward balance take mindfulness, which is a difficult skill to hone in our loud, distracting, manipulative and addictive consumer culture. There’s a lot of social pressure to want more and bigger, to hang on tightly to our things.

But I want less. I want less stuff, less expense, less noise (visual and otherwise), less maintenance, less complication. I want less because I want more. I want more peace, more beauty, more sustainability, more time for loved ones and the activities that are most important to me. Gardening. Animals. Walking. Writing. Playing. Spiritual practice.

I don’t want more than I need. I don’t need more than I can use, enjoy, take care of, or pay for.

I do want to accommodate change, my own, and changing circumstances around me. The simpler and easier my life is, the more space I have to welcome my own aging and wherever my life journey takes me next. I don’t make myself crazy trying to anticipate all the future possibilities, but I want to know I can live well with the resource I have and build reserves for whatever the future brings.

Ironically, it often takes resource to go from more to less. Financial resource. Time and energy resource. It takes sacrifice, in the sense of being willing to give up things valued for the sake of things even more valuable and worthy. In its own way, moving in the direction of living simply is as much work and emotional cost as the endless treadmill of more. It does have an end point, though, whereas more is never satisfied.

Last week I read a post from Joel Tefft titled ‘Abandon, Embrace‘. He suggests daily journaling (which I also highly recommend) using the writing prompts: Today I abandon ___ and today I embrace ___. This is balance in action. What is not helping? What is most important? Abandon something in order to make space for something better.

We can’t find a place for what’s most important if our cup is already too full.

Photo by ORNELLA BINNI on Unsplash

Deciding what kind of a life we want to live and working to create it is a difficult process of choice. It’s difficult because it can be so hard to tell the truth about our needs and feelings. Sometimes we have to give up on cherished dreams and hopes, come to terms with our current limitations. Our choices can affect others in hurtful ways. Sacrifice is not easy. Managing our feelings is not easy.

Choosing, as I’ve said before, involves consequences we can’t always control.

But to make choices, especially difficult ones, is to be standing in our power, as is creating an authentic life that allows us to grow deep roots and be the best and happiest we can be, for ourselves, for our loved ones, and for the world.