by Jenny Rose | Jul 26, 2018 | Connection & Community, Emotional Intelligence, Shadows

I looked up the word “denial” to find a quick definition as a starting point for this post. Fifteen minutes later I was still reading long Wiki articles about denial and denialism. They’re both well worth reading. I realize now the subject of denial is much bigger than I first supposed, and one little blog post cannot do justice to its history and scope.

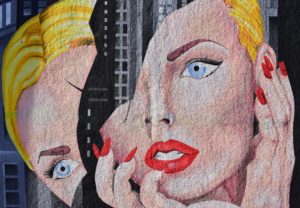

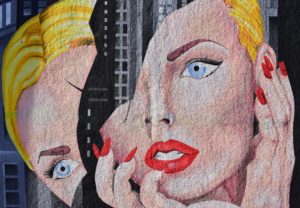

Photo by Ian Espinosa on Unsplash

I wanted to write about denial because I keep tripping over it. It seems to lurk in the background of every experience and interaction, and it’s nearly always accompanied by its best buddy, fear. I’ve lately made the observation to my partner that denial appears more powerful than love in our culture today.

I’ve written before about arguing with what is, survival and being wrong, all related to denial. I’ve also had bitter personal experience with workaholism and alcoholism, so denial is a familiar concept and I recognize it when I see it.

I see it more every day.

I was interested to be reminded that denial is a useful psychological defense mechanism. Almost everyone has had the experience of a sudden devastating psychological shock such as news of an unexpected death or catastrophic event. Our first reaction is to deny and reject what’s happening. Elisabeth Kubler-Ross identified denial as the first of five stages of psychology in a dying patient. Therein lies the distinction between denial as part of a useful and natural cycle and denial as a permanent coping mechanism. In modern psychology denial is followed by other stages as we struggle to come to terms with a difficult event. We (hopefully) move through the stages, gathering our resources to cope with what’s true and coming to terms with the subsequent changes in our lives.

Denialism, on the other hand, is a “choice to deny reality as a way to avoid a psychologically uncomfortable truth” (Wikipedia). For some, denial is an ideology.

In other words, denialsim is all about fear, fear of being wrong, fear of change, fear of painful feelings, fear of loss of power, fear of one’s cover being blown. This is why some of the most rabid and vicious homophobes are in fact homosexual. Unsurprisingly, projection and gaslighting are frequently used by those who practice denialism.

I’ve no doubt denial is an integral part of the human psyche. I never knew anyone who didn’t have a knee-jerk ability to deny. I do it. My partner does it. My friends and family do it. My partner and I have a code phrase: “I’m not a vampire,” that comes from the TV series Angel in a hilarious moment when a vampire is clearly outed by one of the other characters. He watches her put the evidence together: “… nice place… with no mirrors, and… lots of curtains… Hey! You’re a vampire!” “What?” he says. “No I’m not,” with absolutely no conviction whatsoever. It always makes us giggle. If Angel is too low-brow for you, consider William Shakespeare and “the lady doth protest too much, methinks.” Denial is not a new and unusual behavior.

Photo by NASA on Unsplash

The power of denial is ultimately false, however. Firstly and most obviously, denial does not affect the truth. We don’t have to admit it, but truth is truth, and it doesn’t care whether we accept it or not. Secondly, denial is a black hole of ever-increasing complications. Take, for example, flat-earthers. Think for a moment about how much they have to filter every day, how actively they have to guard against constant threats to their denialsim. Everything becomes a battlefield, any form of science-related news and programming; many types of print media; images, both digital and print, now more widely available than ever; and simple conversation. I can’t imagine trying to live like that, embattled and defensive on every front. It must take enormous energy. I frankly don’t understand why anyone would choose such hideous complications. It seems to me much easier to wrestle with the problem itself than deal with all the consequences of denying there is a problem.

Maybe that’s just me.

It seems our denial becomes more important than love for others or love for ourselves. It becomes more important than our integrity, our health, our friends and family, loyalty, and respect or tolerance. Our need to deny can swallow us whole, just as I’ve seen work and alcohol swallow people whole. Denial refuses collaboration, cooperation, honest communication, problem solving and, most of all, learning. Denialism is always hugely threatened by any attempt to share new information or ask questions.

Photo by Jonathan Simcoe on Unsplash

Denial is a kind of spiritual malnutrition. It makes us small. Our sense of humor and curiosity wither. Fear sucks greedily on our power. We become invested in keeping secrets and hiding things from ourselves as well as others. We allow chaos to form around us so we don’t have to see or hear anything that threatens our denial.

This is not the kind of fear that makes our heart race and our hands sweat. This is the kind of fear that feels like a slamming steel door. It’s cold. It’s certain. We say, “I will not believe that. I will not accept that.”

And we don’t. Not ever. No matter what.

A prominent pattern of folks in denial is that they work hard to pull other people into validating them. Denial works best in a club, the larger the better. The ideology of denialism demands strong social groups and communities that actively seek power to silence others or force them into agreement. Not tolerance, but agreement. This behavior speaks to me of a secret lack of strength and conviction, even impotence. If we are not confused about who we are and what we believe, there’s no need to recruit and coerce others to our particular ideology. If you believe the earth is flat, it’s fine with me. I’m not that interested, frankly. I disagree, but that’s neither here nor there, and I don’t need you to agree with my view. When I find myself recruiting others to my point of view, I know I’m distressed and unsure of my position and I’m not dealing effectively with my feelings.

I’ve written before about the OODA loop, which describes the decision cycle of observe, orient, decide and act. The ability to move quickly and effectively through the OODA loop is a survival skill. Denial is a cheat. It masquerades as a survival strategy, but in fact it disables the loop. It keeps us from adapting. It keeps us dangerously rigid rather than elegantly resilient.

Some people have a childlike belief that if something hasn’t happened, it won’t, as in this river has never flooded, or this town has never burned, or we’ve never seen a category 6 hurricane. Our belief that bad things can’t happen at all, or won’t happen again, pins us in front of the oncoming tsunami or the erupting volcano. It allows us to rebuild our homes in places where flood, fire and lava have already struck. We ignore, minimize or deny what’s happening to the planet and to ourselves. We don’t take action to save ourselves. We don’t observe and orient ourselves to change.

Some things are just too bad to be true. I get it, believe me. I’m often afraid, and I frequently walk through denial, but I’m damned if I’ll build a house there. The older I get, the more determined I am to embrace the truth. I don’t care how much pain it gives me or how much fear I feel. I want to know, to understand, to see things clearly, and then make the best choices I can. It’s the only way to stay in my power. I refuse to cower before life as it is, in all its mystery, pain and terrible beauty.

Ultimately, denial is weak. I am stronger than that.

Photo by Joshua Fuller on Unsplash

All content on this site ©2018

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted

by Jenny Rose | Jul 19, 2018 | A Flourishing Woman, The Journey

In the used bookstore in which I volunteer, I found a slim paperback book of poetry, modestly and plainly bound, entitled A Gypsy’s History of the World, by Kim Robert Stafford. It called to me and I bought it for $4.00.

Photo by Syd Wachs on Unsplash

I had never heard of this poet, but he turns out to be quite well-known and has published several books, which I’ll be looking for now. In the meantime, this book is filled with treasures.

For a couple of days I’ve been groping for this week’s post. Sometimes they come so easily, these posts. Other times I flounder. It seems that the more I have going on, the harder it is to come up with a focused essay. Irritating, but writing can be like that.

When I listen to the sound of my life this week I hear a cacophony. There are the half-excited, half-apprehensive feelings I have as the night approaches on which I’ve scheduled a local venue to once again try to start a dance group. (Will I be a good leader? Will they like me? Will anyone come?) There’s the increasing pressure I feel to find a way to earn a paycheck. There are new friends and our conversations as we strengthen our connections. (Am I talking too much? Am I offensive? Am I too blunt? Do I ask too many questions?) I’m preoccupied with family dynamics and past, present, and future possibilities and fears. (What’s the right thing to do? What’s loving? What’s useful? What will people think about me? How do I take care of everyone’s needs and expectations? How much irreparable damage will I do if I make the wrong choice?) There are my weekly activities and appointments. All the material of my daily reading swirls in my head, awaiting synthesis and integration.

In my creative world, I’m with Pele, the Earth-Shaper, sensual, passionate and angry. This week others will come to dance with her, to make offerings, to propitiate and reconnect. Revolving around her are other characters: Rumpelstiltskin the dwarf; Poseidon, the Greek god of the sea; a little brown bat called Ash and his companion, a bark beetle; the eldest of the twelve dancing princesses, Ginger; an old woman, Heks, apprentice to Baba Yaga; and Persephone, who comes to drum for the dance.

All this, and I can’t come up with a thing to post about.

I know this dynamic. The more pressure I put on myself, the harder I try, the more elusive inspiration will be.

Photo by Pascal Müller on Unsplash

It’s a foggy morning here in Maine. Foggy and oppressive with high humidity and a threat of severe weather this afternoon. I’m planning on meeting a new friend for a walk and then I’ll swim. I decided to stop trying to write a post. I turned off all the lights up here in my little attic space and lit a candle. I picked up A Gypsy’s History of the World and turned back to the beginning of the book.

Duets

A dream flips me into the daylight.

I pry my way back:

a door opens, I enter, never

escape; the jailor sings by morning

duets through the bars with me.

I wake and out my window

by dawn a blackbird sings and

listens, sings and listens.

Listen. Thistledown jumps its dance

in the wind. I’m small and have

no regrets. Yesterday is a temporary

tombstone, a hollow stalk

on the hill. I’m putting my best

ear forward; in the space between songs

I’m travelling. My hands make

whistling wings in the wind.

No things meet without music:

wind and the chimney’s whine, hail’s click

with the pane, breath in a bird’s

throat, rain in my ear when I

sleep in the grass. I miss the

whisper of a swallow’s wings

meeting the thin air somewhere far.

Branches of my voice, come back.

Inside each song

I’m listening.

At once the cacophony in my head faded away, no more than the murmur of the trees and breeze or the ocean’s breath. For a few minutes, I thought about being small and having no regrets, let alone imagining future regrets. Yesterday and yesterday and yesterday, all temporary tombstones. All my yesterdays add up to almost 20,000 hollow stalks on a hill. And yes, activities and schedules, efforts and appointments, hopes and fears, words and information, friends and family, the way the shadowed ceiling looks in a sleepless hour and the path of silent tears on their way to my pillow. All of that. But I forget about the space between all those songs. I forget that I’m traveling through this place, this life, and these landmarks.

Photo by Dakota Roos on Unsplash

Sometimes I forget to just listen to life’s music, just witness, just be present and still. Sometimes I forget to fold my hands in my lap and watch the wavering shadows the candle makes inside the song of my life. The song will not be endless. One day it will be yesterday’s song, held in a hollow stalk on a hill. I can’t reach out my hand and clutch it, pin it down, record it and make sense of it. I don’t need to. I don’t want to.

Today, friends, I’m listening.

My daily crime.

All content on this site ©2018

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted

by Jenny Rose | Jul 12, 2018 | Emotional Intelligence, Feelings

I’ve been thinking about loyalty recently. Loyalty is one of my bigger rabbit holes. I most often use the term when I’m beating myself up. A nasty little internal voice frequently hisses “Disloyal!” in my ear. This happens so constantly, in fact, that I’m bored. I’ve decided to unpack the concept of loyalty, spread it out, let the cat sniff at it, and either own my own disloyalty without shame or permanently silence that particular internal accusation.

The first thing I notice is I want to be loyal. Loyalty is a virtue. Good, loving people are loyal. I certainly want to be a loyal family member, friend and partner. Loyalty has always been an important part of my identity, which is why it’s such an effective lash for me. What’s more shameful and ugly than disloyalty?

I don’t want to be shameful and ugly. If I am shameful and ugly, I certainly don’t want anyone to find out.

Loyalty, then, is something that depends on what onlookers think about my behavior and choices.

Before I’ve even crawled into the mouth of the rabbit hole I’ve moved out of my power. Interesting.

Photo by Kevin Quezada on Unsplash

Recently, I took my morning cup of tea and spent two hours with dictionary, thesaurus and my laptop looking at poetry, quotes, memes, definitions and articles. I read about families, patriotism and dogs. I discovered 80% of results returned for a search on loyalty have to do with manipulating customer and product loyalty. Of course. What a world.

At the end of that two hours, I felt no wiser. I had some notes, but I still didn’t have a clear idea of what loyalty really is, what it looks like, what it feels like to give or receive it, and how it overlaps with trust, authenticity, truth, enabling, coercion and control. I can point to people in my life I feel loyalty for, and I can point to people who I feel are loyal to me, but the truth is I don’t trust myself on this issue. Maybe my confusion means I am, in fact, shamefully disloyal. A humbling and humiliating thought.

At the same time, would I feel so torn apart by family and personal social dynamics if I was thoroughly disloyal? My sense of loyalty to others has given me much anguish over the years. Surely if it was absent in me I wouldn’t struggle so hard with it.

Simply defined, loyalty is a strong feeling of support or allegiance. That definition leaves me even more clueless than I was before. It has to be more complicated than that, doesn’t it?

Well, doesn’t it?

Is it just me, or does the cultural definition of loyalty consist of a much more convoluted hairball of expectations, assumptions and false equivalencies?

I often use back doors when I feel stuck. My two hours of research did give me some ideas about what loyalty is not, at least in my mind. But already I can see others might disagree. Still, that’s why we have dictionaries and definitions.

Loyalty cannot be slavery or prostitution. If I have to compromise my integrity in order to fulfill someone else’s expectation of loyalty, it’s no longer a virtue, but an abuse and manipulation. True loyalty must be freely and heartfully given. Authentic loyalty can’t be bought, sold, stolen or owed. It’s not demonstrated by obedience or compliance. If it’s not free and spontaneous, it’s only a sham, an empty word that sounds great but has no substance. Loyalty is not a weapon. It’s a gift.

Said another way, from a perspective of power (and you know how much I think about power!), loyalty is a tool of power-with, not a weapon of power-over.

Photo by Seth Macey on Unsplash

Loyalty is not blind. Part of its value is its clarity. We prize it so highly because seeing and being seen clearly, warts and all, and demonstrating or receiving loyalty in spite of it is an act of strength and love. In that case, compassion, tolerance and respect are all involved in loyalty. It follows, then, that loyalty does not require agreement. I can feel entirely loyal to a loved one while disagreeing with some of their choices and beliefs.

Loyalty does not imply denial, arguing with what is or colluding in rewriting history in order to sanitize it. Loyalty is not a right or an obligation.

In fact, the thesaurus suggests the word “trueness” as a synonym for loyalty. Interesting. Isn’t trueness the same as authenticity? I count on those who are loyal to me to tell me the truth of their experience with me and of me. I count on them to trust me with their thoughts, feelings, concerns and observations. I count on them to ask me questions about my choices, and to forgive me when I’m less than perfect. I hold myself to the same standards. This can mean a hard conversation now and then, and uncomfortable vulnerability and risk, but real loyalty is not cheap.

The thesaurus also supplies the word “constancy” as a synonym for loyalty. Constancy is an old-fashioned word these days, but it leapt out at me because consistency is very important to me. I’ve had some experience with Jekyll-and-Hyde abuse patterns in which the goalposts and rules constantly change without notice, keeping me nicely trapped in trying to please people who have no intention of ever being pleased no matter what I do. Loyalty is present one day and absent the next, then present again, then unavailable. That kind of “loyalty” is an abuse tactic.

As always, the construct of loyalty is two-sided. There’s the loyalty that extends between me and another, and then there’s the loyalty I extend to myself. This circles back around to slavery, prostitution and silence. If I have to betray my own needs or make myself small in order to earn or retain someone’s loyalty, something’s very wrong. If I’m called disloyal for saying no, having appropriate boundaries or telling the truth of my experience, then we are not in agreement about the definition of loyalty or I’m being manipulated (again). How loyal can I be to others if I fail to be faithful to myself?

True loyalty will never require me to make a choice between myself and another. Loyalty is strong enough to compromise and collaborate.

Loyalty becomes weaponized when we demand or command absolute agreement, devotion and unquestioning support. Then the concept becomes very black and white. This is demonstrated all over social media and media in general. One unwanted question or view leads to unmerciful deplatforming, silencing and a torrent of threats and abuse. Our loyalty is questioned and tested at every turn. We allow bullies, tyrants and personality-disordered people to achieve and maintain control, terrified of tribal shaming, being unpatriotic or being cast out of our social groups and communities.

The label of disloyalty is extremely powerful, but when I strip away all my confusions and distortions around loyalty and return to the simple definition, it’s not complicated at all. I certainly feel a strong allegiance and support for many individual people, for my community, for my country, for women, for writers, for this piece of land I live on, and for myself.

I suspect many others would like me to wear the label of disloyalty, but I can’t do a thing about their distortions except hand them a dictionary. Very elitist behavior, I’m sure you will agree. Not to mention the disloyalty of refusing to collude in my own shaming.

Being called disloyal doesn’t make it so.

That voice in my head has to do better, find a new slur. I’m willing to own being disloyal if I am, but my conclusion after this investigation is mostly I’m not, and when I am, my greatest trespass is against myself. That I can do something about.

Loyalty. Setting down the weapon. Picking up the tool.

Photo by David Beale on Unsplash

All content on this site ©2018

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted

by Jenny Rose | Jun 7, 2018 | Aging, Connection & Community, Emotional Intelligence

Have you ever had a dream of finding an undiscovered room in a familiar house? I have, several times. I like those dreams. A large piece of furniture moves aside, or I walk into a room I know well and find a new door in it.

Last weekend, my partner and I went to our small local theater and I saw Book Club while he went happily off to Deadpool. (Honestly, I’m so tired of comics, superheroes, space adventures, special effects and unending battles and chases. Whew. It felt good to say that.)

The movie was a relief. I didn’t have to spend most of it with my eyes shut trying to filter out the entirely overstimulating and, at the same time, boring hyperactivity, and it wasn’t excellent. It didn’t require anything from me except to sit back and relax.

No spoilers and this is not a movie review, but Jane Fonda tries way too hard. Instead of marveling at her artificial youthfulness, I felt rather sorry for her. There was also a lot of unnecessary drinking. It didn’t add anything to the story. Some of the humor was more of a wince than a chuckle, but there were some truly funny moments. The writing was a little inconsistent. It’s a movie about connection and being an aging woman.

Overall, I could relate to these four women and I found the movie oddly touching in an unexpected way. I’ve been thinking about it ever since, in fact, trying to understand why it made me feel so bittersweet.

It has to do with giving up. Well, not really. Not giving up, exactly, but settling. No, that’s not quite right, either.

It has to do with gradually forgetting to entertain possibility.

That’s better.

Photo by Joshua Rawson-Harris on Unsplash

We inhabit our lives like a house. It’s a finite space, and we’re intimately familiar with the floorplan, the closets, the windows and the doors. Our house is defined by ourselves and the way we live, and it’s also defined by the external world and people around us. Outside our house is a world where all kinds of potential physical and emotional harm crouches, waiting for us to take a risk and leave our shelter. Outside our house is a wilderness of Unknown.

When we’re young the house of our life is new and exciting. We experiment using the space in different ways. We begin to figure out what we like and don’t like, what works well in our lives and what doesn’t, who we can live with and who we can’t live with. We gradually accumulate furniture in the forms of memories, scar tissue, hand-me-downs, beliefs, and new stuff we find all by ourselves.

The years go by and we learn a lot (hopefully) about the way the world works and who we are. We notice an ever-enlarging population of people younger than we are.

Then, one day, we’re in our fifties. Then our sixties. Then our parents are old. Not older. Old. How did that happen? Then our kids are as old as we were when we had them. It’s entirely disconcerting. We begin to think of ourselves as middle-aged and secretly feel older than that a lot of the time. Then, if you’re a woman, comes menopause, which, just as the onset of menstruation changed everything in the beginning of our lives, remodels our house.

For one thing, we need to tear out the heating system and replace it with cooling and fans.

Photo by Ian Espinosa on Unsplash

By this point in my own life, I’ve made a lot of choices and taken notes on how they worked out. I’ve made decisions about what I will and won’t do, and about what I am and am not interested in. I’ve decided what dreams to discard and interests to drop, because I’m out of time, energy or both. I’ve decided I know exactly who I am, what I’m capable of and what I need and want. I have an entirely private (because it’s shameful) list of things I’ve given up on.

Book Club speaks to the ways in which we begin to limit possibility as we age. In my case, it has nothing to do with age, though. I’ve been slamming doors behind me my whole life. When I was 18, I turned my back on high school. When I was 20, I left residential college, never to return. When I was 21 and got married, I gave up on dating or looking for love. When I was 27 and had my first child, I stopped dreaming of freedom and adventure.

And so on.

Of course deciding we’re never going to do something ever again practically guarantees the Gods will throw it back to us sooner or later, giggling. Now when I hear myself say, “Never again…” I can smile.

An even darker aspect of refusing possibility has to do with the dreams and desires we’ve never fulfilled. I’ve always struggled with financial scarcity. I tell myself nearly every day I’ll never be financially successful, and it doesn’t matter, because I have a good life, I have what I need, I’d rather have my self-respect and integrity than be rich (note the belief one can’t have both), and it’s not a big deal. I say all those things to myself because I don’t see any possibility of financial security. If I haven’t found it following all the rules and working so hard, then maybe I don’t deserve it, or it’s just not something I can earn or have. I don’t want to live the rest of my life hoping for something that never happens.

The story I tell myself is I’d love to find a great job where I could contribute my talents, do meaningful work, be part of a team and get adequately paid. I’m always watching and listening for that job. But I know I’m too old, the things I love to do will never pay well, the kind of thing I’m looking for wouldn’t be here in rural Maine, and I’ll struggle to maintain adequate housing and feed myself forever.

If there’s no possibility, I can work on accepting what is and try to be peaceful.

Photo by Nathan Dumlao on Unsplash

Book Club was redemptive. It reminded me possibility still exists for me. I’ve done things in the last five years I never imagined doing in my wildest dreams. Why do I think it’s all over now? Why do I make so many iron-clad assumptions about the size and shape of my house? Why am I deliberately trying to ditch my dreams? Why do I think of myself as a food item on the pantry shelf with an expired sell-by date?

Am I too old and jaded to invite miracles? Am I too worn out to move a piece of furniture (a bookcase, what else?) and discover a door behind it I never saw before? I know I’ve yet to discover my highest potential.

Maybe I’m just not very brave. I don’t want to fail anymore. I don’t want to be disappointed or feel I’m a disappointment, ever again. I don’t want to be let down, or hurt, or stood up or rejected. I don’t want to look like a fool. (I don’t mind being a fool, but I don’t want to look like one.) I don’t want to be scared.

I don’t want to play power games with people.

Perhaps this is the crust of old age, this gradual accumulation of weariness, scar tissue, limiting beliefs, and physical changes that keeps us sitting in our familiar, safe house, where the edges and boundaries are well-defined and unchanging and we control the dangers of possibility.

Some people successfully shut out life, or shut themselves away from it. I’m never (there I go again) going to be able to pull that off, though. I’m too curious and too interested. An overheard remark, a movie, a conversation, a book or even a song lyric invariably comes along and kicks me back into motion when I’m threatening to lock myself permanently in the predictability and safety of my house. Then I begin to write, and the walls waver and shimmer, new doors and windows appear, a corner of the roof peels away to show me the sky, and I remember I’m still alive, still kicking, still wanting and needing and still, in spite of my best efforts, dreaming of possibilities.

Photo by frank mckenna on Unsplash

All content on this site ©2018

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted

by Jenny Rose | May 31, 2018 | Connection & Community, Emotional Intelligence

A couple of years ago my adult son and I had a heated exchange during which I asked him exactly what he wanted from me. It was a useful question. For a moment we stopped being adversaries while he thought about it. “Umm, I don’t know. What I’ve always had, unconditional love, I guess.”

Photo by Jordan Whitt on Unsplash

That moment has stayed with me, because as I asked the question I realized I really didn’t know, and I was both curious and interested. What does a fully emancipated twenty-something-year-old man honestly want from his mother? It was the first time it ever occurred to me to ask either of my sons what they wanted from me at any age or stage.

I never thought of anything except what I wanted to give them.

I’ve been reading about emotional labor recently, which leads me irresistibly to the concept of benign neglect.

Emotional labor is the often invisible process of managing feelings and their expressions as part of a job or relationship. The idea often comes up as part of the ongoing discussion about gender roles and equality, but I’m thinking about it in a slightly different context.

Benign neglect is a term that originated out of city planning politics and now also describes an attitude of inaction regarding an unproductive situation one is commonly held to be responsible for.

I’ve written before about pleasing people, boundaries and reciprocity. Emotional labor is embedded in all of these, and it’s been a primary dysfunction in my relationships over the years, though I haven’t had any language or distinction about my experience of it until recently.

If you Google emotional labor you find definitions, descriptions, assertions about the disproportionate burden of emotional labor on women, and the powerful but invisible expectations regarding who is responsible for emotional labor in any given situation. What you don’t find is discussion about how to make visible and support the vital aspect of emotional labor in community, jobs and families. The discussion stops at equal rights.

Equal rights is an important discussion to have, but in the meantime we’re dealing with families, friends and jobs today and emotional labor is an inescapable need right now.

I think of emotional labor as glue. You don’t see it, but if it’s missing everything falls apart. If it’s applied carefully it holds things together. If we don’t keep a calendar and glance at a clock now and then, we can’t manage our lives. Either we learn to cope with appointments, deadlines, commitments, grocery lists and feelings ourselves or we rely on someone else to do it for us. Part of adulting is learning emotional labor.

Photo by freddie marriage on Unsplash

I’m a button sorter by nature, and I take a lot of pleasure in being organized. My life works better when I take the trouble to be effective and efficient, and it gives me pleasure to share with my loved ones the benefits of thinking and planning ahead and taking care of business. Remembering special dates, buying tickets, planning for bake sales and decorating for the holidays have all been offerings symbolizing my love and willingness to provide support to my family, along with the daily activity of simply showing up in my relationships.

I said that recently to my partner — “this is me showing up in the relationship.” He had no idea what I meant.

I was staggered. What do you mean, what do I mean? You know, asking if you slept well because you didn’t the night before. Or inquiring about the status of that headache you complained about yesterday. Or asking you what’s in your attention and what you’d like to do today. Listening. Sharing. Showing concern. Demonstrating I appreciate you enough to be present. Reminding you that we’re almost out of cat litter. Thanking you for patching the mousehole in the cupboard. Showing up in the relationship!

Photo by Ester Marie Doysabas on Unsplash

Yeah. Aka emotional labor.

He listened and shrugged. I didn’t describe anything he could relate to. He lives his life with me without showing up or not showing up. He just does what he does, says what he says, is interested in what he’s interested in. He doesn’t check in with himself every day to be sure he “showed up” in a way that reassures me of his ongoing affection and caring.

I do.

I’ve thought a lot about this since that conversation. I’ve been conscious of a huge annoyance and, underneath that, amusement.

All my emotional labor is completely unneeded. He never asked me to do it. It’s not useful. It’s invisible to him.

This made me wonder if that’s been true in all my other relationships as well, including with my kids, historically and presently.

That’s not right, though, because I’ve been with some real man-babies. My husband once called me at work because the baby had a soiled diaper. (Okay, it was a real blow-out, but still!) Then there was the guy who wanted a dog to fish with, but didn’t want to walk it, poop scoop after it or stay up all night on July Fourth holding its paw because it was terrified of firecrackers and invariably went into seizures (it had epilepsy).

And then there were the kids. There’s no question at all that raising kids takes a lot of emotional labor. It’s both needed and required.

Photo by Chris Barbalis on Unsplash

I guess I just got into the habit. Emotional labor has been my offering, my contribution, in every relationship. I’m good at it. Until very lately, I never considered reciprocity and I had no definition for emotional labor. I just thought of it as being a good woman.

When my son said he wanted what I’d always given, unconditional love, I had a moment of real satisfaction. I made so many mistakes, but at least I did that right. On the other hand, can those two simple words ever encompass the totality of heart, pain, frustration, energy, loyalty and years they represent? Unconditional love. That’s all.

Right.

I was with a man for a long time who had no interest in emotional labor. Once he had me hooked, he was never decisive, confident or clear again. He initiated no physical contact. He resisted making any plans. He made no effort to develop rituals, routines or regular check-ins. His job was stressful, he had some sleep and health issues, and his favorite excuse was “I forgot.” I gave and he withheld.

Eight years later (slow learner) burned-out, anguished and desperate, it occurred to me to wonder what would happen if I. Just. Stopped.

So I did. I stopped e-mailing. I stopped calling. I made plans without him. I let go of all my expectations and started trying to glue myself back together. I worked, took care of my own responsibilities, enjoyed time with friends and family and went on with my life. I set down all that emotional labor and walked away from it.

Guess what happened?

He floated away.

I’d essentially had an eight-year relationship with myself.

He did eventually (weeks) notice I wasn’t around any more and got in touch, mildly puzzled and reproachful. I was casual and said I’d been busy.

He told me he didn’t feel like he was getting the attention he needed from me. We were sitting in his car at the time. I’ll never forget it.

Until now, I’ve never put that experience in context with all my other relationships. After my recent conversation with my partner about showing up in the relationship, I changed my behavior. I stopped worrying about “showing up” every day. I’ve engaged with my own needs, daily tasks and schedule. I enjoy our time together, but I’ve stopped trying to make it happen. I switched my focus to making sure I show up for myself every day.

What I’ve learned from all this is emotional labor is real and largely unconscious. Many of us give our lives to it. I’ve also learned it’s a choice. When it remains invisible and undefined and we’re operating out of unspoken cultural expectations, we become unconscious of much of our decision-making and motivation. Our desire to be a “good” wife, mother, daughter, lover, sister, whatever, becomes all-powerful and we throw ourselves into it without ever thinking about whether that’s what others want and/or need from us. We don’t consider asking for help or professional support if we’re caregivers. In fact, we feel hurt when our emotional labor of worrying, for example, is not received with gratitude and appreciation! If whoever we’re connected with does want our emotional labor and provides none themselves, we don’t notice. We just work harder.

This is where benign neglect comes in. Benign neglect is an attitude of inaction regarding an unproductive situation one is commonly held to be responsible for, remember? The culture may hold us to be responsible for a lot of things, but that doesn’t make it true.

What if we challenged the “commonly held” belief that all emotional labor is our job in any given relationship? What if we decided it’s not our responsibility, in addition to not being useful, to worry, fuss, organize or manage the feelings of the people around us? What if we took back our power to choose?

Photo by Bruno Nascimento on Unsplash

If I had stopped worrying about doing laundry for my teenagers, or insisting on family mealtimes, or keeping track of their schedules, what then? The sad truth is I was afraid people would think I was a bad mother. I knew I would think I was a bad mother. The kids didn’t do those things for themselves, so I had to do it in order to demonstrate my love, commitment and competence. What kind of a mother lets her kids wear dirty socks?

I didn’t consider the difference between organizing schedules for toddlers and organizing two big, smart, capable boys who saw no reason to bother themselves with boring things like schedules, grocery lists and clean socks. I was so busy demonstrating my feelings, especially my love for them, I never stopped to wonder if they were learning to express their feelings. I didn’t ask.

It annoys me that only now am I seeing ways in which I could have been a much more effective parent, partner, daughter and sister.

At bottom, I don’t think emotional labor is about equal gender rights at all. I think it’s about choice, and choice is about power. We can’t choose if we don’t recognize there is a choice, we can only stumble forward blindly, doing our best with what we think the rules and expectations are, external and internal, until, overburdened, overwhelmed and exhausted, we fall down and don’t get up again. Meanwhile, the people we love, the ones we’re doing all this labor for, are not saved by our labor. Kids grow up, have car accidents and bad relationships, choose crappy diets, fall into addiction, catch an STD. Parents grow old, have health problems, and become dependent. Siblings, friends, lovers and mates are not assisted by our worry, our ability to manage their feelings or our “showing up” in the relationship. All our loved ones might be a great deal better off if we hadn’t taken on all the emotional labor ourselves, because when life happens, as it inevitably does, they lack the skills we never let them learn because we were so busy being good women.

Also, when was the last time you were thanked for all your emotional labor? (What do you mean, “showing up” in the relationship?)

You gotta love the irony of the whole thing.

What would my relationships look like if I kept my emotional labor in balance with the labor of those I’m connected to? What if I could be more like my partner and trust that my affection and love for him (and others) are communicated and understood without such deliberate emotional labor? He just naturally demonstrates his feelings for me in our day-to-day life without all this effort and trying. What if I relaxed and redefined what being a “good woman” means?

I’m going to find out.

Photo by Ryan Moreno on Unsplash

All content on this site ©2018

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted