by Jenny Rose | Jun 7, 2018 | Aging, Connection & Community, Emotional Intelligence

Have you ever had a dream of finding an undiscovered room in a familiar house? I have, several times. I like those dreams. A large piece of furniture moves aside, or I walk into a room I know well and find a new door in it.

Last weekend, my partner and I went to our small local theater and I saw Book Club while he went happily off to Deadpool. (Honestly, I’m so tired of comics, superheroes, space adventures, special effects and unending battles and chases. Whew. It felt good to say that.)

The movie was a relief. I didn’t have to spend most of it with my eyes shut trying to filter out the entirely overstimulating and, at the same time, boring hyperactivity, and it wasn’t excellent. It didn’t require anything from me except to sit back and relax.

No spoilers and this is not a movie review, but Jane Fonda tries way too hard. Instead of marveling at her artificial youthfulness, I felt rather sorry for her. There was also a lot of unnecessary drinking. It didn’t add anything to the story. Some of the humor was more of a wince than a chuckle, but there were some truly funny moments. The writing was a little inconsistent. It’s a movie about connection and being an aging woman.

Overall, I could relate to these four women and I found the movie oddly touching in an unexpected way. I’ve been thinking about it ever since, in fact, trying to understand why it made me feel so bittersweet.

It has to do with giving up. Well, not really. Not giving up, exactly, but settling. No, that’s not quite right, either.

It has to do with gradually forgetting to entertain possibility.

That’s better.

Photo by Joshua Rawson-Harris on Unsplash

We inhabit our lives like a house. It’s a finite space, and we’re intimately familiar with the floorplan, the closets, the windows and the doors. Our house is defined by ourselves and the way we live, and it’s also defined by the external world and people around us. Outside our house is a world where all kinds of potential physical and emotional harm crouches, waiting for us to take a risk and leave our shelter. Outside our house is a wilderness of Unknown.

When we’re young the house of our life is new and exciting. We experiment using the space in different ways. We begin to figure out what we like and don’t like, what works well in our lives and what doesn’t, who we can live with and who we can’t live with. We gradually accumulate furniture in the forms of memories, scar tissue, hand-me-downs, beliefs, and new stuff we find all by ourselves.

The years go by and we learn a lot (hopefully) about the way the world works and who we are. We notice an ever-enlarging population of people younger than we are.

Then, one day, we’re in our fifties. Then our sixties. Then our parents are old. Not older. Old. How did that happen? Then our kids are as old as we were when we had them. It’s entirely disconcerting. We begin to think of ourselves as middle-aged and secretly feel older than that a lot of the time. Then, if you’re a woman, comes menopause, which, just as the onset of menstruation changed everything in the beginning of our lives, remodels our house.

For one thing, we need to tear out the heating system and replace it with cooling and fans.

Photo by Ian Espinosa on Unsplash

By this point in my own life, I’ve made a lot of choices and taken notes on how they worked out. I’ve made decisions about what I will and won’t do, and about what I am and am not interested in. I’ve decided what dreams to discard and interests to drop, because I’m out of time, energy or both. I’ve decided I know exactly who I am, what I’m capable of and what I need and want. I have an entirely private (because it’s shameful) list of things I’ve given up on.

Book Club speaks to the ways in which we begin to limit possibility as we age. In my case, it has nothing to do with age, though. I’ve been slamming doors behind me my whole life. When I was 18, I turned my back on high school. When I was 20, I left residential college, never to return. When I was 21 and got married, I gave up on dating or looking for love. When I was 27 and had my first child, I stopped dreaming of freedom and adventure.

And so on.

Of course deciding we’re never going to do something ever again practically guarantees the Gods will throw it back to us sooner or later, giggling. Now when I hear myself say, “Never again…” I can smile.

An even darker aspect of refusing possibility has to do with the dreams and desires we’ve never fulfilled. I’ve always struggled with financial scarcity. I tell myself nearly every day I’ll never be financially successful, and it doesn’t matter, because I have a good life, I have what I need, I’d rather have my self-respect and integrity than be rich (note the belief one can’t have both), and it’s not a big deal. I say all those things to myself because I don’t see any possibility of financial security. If I haven’t found it following all the rules and working so hard, then maybe I don’t deserve it, or it’s just not something I can earn or have. I don’t want to live the rest of my life hoping for something that never happens.

The story I tell myself is I’d love to find a great job where I could contribute my talents, do meaningful work, be part of a team and get adequately paid. I’m always watching and listening for that job. But I know I’m too old, the things I love to do will never pay well, the kind of thing I’m looking for wouldn’t be here in rural Maine, and I’ll struggle to maintain adequate housing and feed myself forever.

If there’s no possibility, I can work on accepting what is and try to be peaceful.

Photo by Nathan Dumlao on Unsplash

Book Club was redemptive. It reminded me possibility still exists for me. I’ve done things in the last five years I never imagined doing in my wildest dreams. Why do I think it’s all over now? Why do I make so many iron-clad assumptions about the size and shape of my house? Why am I deliberately trying to ditch my dreams? Why do I think of myself as a food item on the pantry shelf with an expired sell-by date?

Am I too old and jaded to invite miracles? Am I too worn out to move a piece of furniture (a bookcase, what else?) and discover a door behind it I never saw before? I know I’ve yet to discover my highest potential.

Maybe I’m just not very brave. I don’t want to fail anymore. I don’t want to be disappointed or feel I’m a disappointment, ever again. I don’t want to be let down, or hurt, or stood up or rejected. I don’t want to look like a fool. (I don’t mind being a fool, but I don’t want to look like one.) I don’t want to be scared.

I don’t want to play power games with people.

Perhaps this is the crust of old age, this gradual accumulation of weariness, scar tissue, limiting beliefs, and physical changes that keeps us sitting in our familiar, safe house, where the edges and boundaries are well-defined and unchanging and we control the dangers of possibility.

Some people successfully shut out life, or shut themselves away from it. I’m never (there I go again) going to be able to pull that off, though. I’m too curious and too interested. An overheard remark, a movie, a conversation, a book or even a song lyric invariably comes along and kicks me back into motion when I’m threatening to lock myself permanently in the predictability and safety of my house. Then I begin to write, and the walls waver and shimmer, new doors and windows appear, a corner of the roof peels away to show me the sky, and I remember I’m still alive, still kicking, still wanting and needing and still, in spite of my best efforts, dreaming of possibilities.

Photo by frank mckenna on Unsplash

All content on this site ©2018

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted

by Jenny Rose | May 10, 2018 | Connection & Community, Emotional Intelligence, Shadows

Slowly, I’m finding online communities of writers. As I’ve shaped Our Daily Crime, I’ve connected with other bloggers. These connections mean I spend at least an hour a day reading the work of others. I’m inspired, touched, tickled and provoked, and I feel at home in these digital communities because we all share the need to write and be read. We also share self-doubt, confusion, vulnerability, loneliness, the need for connection and the problem of earning a living.

Photo by Volkan Olmez on Unsplash

Over and over again, I read about personal struggles with depression, fear and anxiety. Many a writer sits down to their daily writing practice with goals and intentions and finds him or herself unable to do anything but express the here and now of their experience of ambivalence, avoidance, distraction or block. To be a writer is to occasionally live with shame and guilt about what we meant to write, what we should have written and the quality and subject of what we actually did come up with. We all doubt our ability, our value, and whether anyone will care enough to read our words. Creative expression is a daily leap of faith.

I’ve struggled all my life with depression. In more recent years, I’ve come to understand anxiety and fear are also large parts of the feeling I recognize as depression. Over the years I’ve tried to manage depression in many ways. Some worked, at least temporarily, and some didn’t.

It hasn’t been until the last decade that I’ve finally found a way to effectively manage and even largely banish depression. It doesn’t play with me anymore. Fear and anxiety still show up regularly, but the same method works to manage them, and I no longer worry one day I’ll just give up, step over some unseen edge, and disappear into crazy, a fugue state, or death.

One day, for no reason in particular except I felt exhausted, despairing, and bored with both, I said to Depression, “You win. I give up. Why not come out of the shadows and show yourself?”

Fat and happy, secure in its power, it did just that.

The first thing that I realized was Depression is an experience, not an integral piece of me. It’s something draped around me. It can be separated from me.

The second thing I noticed was my depression is male. He walked with an arrogant male strut and swagger and he spoke in a male voice.

I didn’t name him because he wasn’t a pet, he wasn’t a friend, and he most definitely wasn’t invited to be a roommate. He was merely someone who showed up at more or less regular intervals and made a nuisance of himself. He didn’t have the manners to knock on the door, wait to be invited or give any notice of his arrival. He just appeared.

I wondered what it would take to discourage him from visiting. What made me so attractive?

Photo by Stefano Pollio on Unsplash

Clinical depression is like a grey cave filled with fog. It numbs the senses and fills head and heart with cold, sticky, lumpy oatmeal. One is entirely alone with no hope. The simplest action, like opening one’s eyes, takes enormous effort. Depression envelopes and consumes every spark of power.

The only reason I’m in the world today is because I’m an unbelievably stubborn butthead. I’m also very nice. One does not cancel out the other, but nearly everyone persists in missing that second important point, with the result that I’m constantly being underestimated. This is a wonderful advantage in life.

Depression was no exception to the rule. When invited, he disentangled himself from me, parked his butt in a chair I pulled out for him, and began to tell me how things were going to be from now on.

On that particular day, I hadn’t showered (or the day before that, or the day before that). Annoyed by his high-handedness, I interrupted to say I was going to shower. He told me not to. Who would care? What was the point? I wouldn’t see anyone. No one would see me.

That was all I needed. I went and took a long shower. Washed my hair. Shaved my legs. Put on clean clothes and some jewelry. Depression sat in the bathroom and muttered at me. I ignored him.

I felt better then, and my irrepressible creativity began to stir, along with a childlike streak of playfulness I usually keep well-hidden. One small act of rebellion had helped me regain a tiny sense of power.

One of the things that used to happen when depression struck was that I stopped eating. I’d go all day with nothing but a salad and a piece of toast. I hadn’t eaten a solid meal for several days on this occasion. I wasn’t the slightest bit hungry (this is common), but I knew I needed to eat.

Depression didn’t like it. He threatened and complained and trotted out all the usual points. I was too fat. I hadn’t been doing anything useful and didn’t need to eat. I didn’t make enough money to deserve to eat.

Photo by Florencia Potter on Unsplash

I put a chair at the table for Depression (I lived alone at the time), invited him to sit, set the table for two with complete place settings, right down to two glasses of water, made myself a meal, and ate. I offered him some food, but he refused. I read while I ate and ignored Depression, who sat and sulked.

Well, you have the idea. The more he protested when I wanted to take a walk, sit in the sun or work in the garden, the more stubborn I became. I politely invited him to join me in my activities, but he refused, which meant the more I got out in the world and did things the less time I spent with him. He hated my movies and my audio books. He thought walking to Main Street for an ice cream cone was a criminal waste of money, along with feeding the birds. The only activity he approved of was my work, which involved sitting for hours in front of my computer with headphones on doing medical transcription as fast and accurately as possible for only slightly more than minimum wage.

He absolutely hated my music. I quickly developed the habit of turning on Pandora first thing every morning and listening to it most of the day.

We also conflicted over sleep. Depression said there was no point in getting up in the morning because no one would notice. No one would care. In fact, the only things really worth doing in life were working and sleeping. This attitude ensured I set the alarm for 5:30 a.m. and walked every day at dawn.

I didn’t ask him to leave. I didn’t fight or struggle. I made sure he had plenty of space and a good pillow in my bed. I gave him a spot at the table and a seat in front of the TV. I took out a clean towel for him and invited him to browse in my personal library.

Every single time he told me not to do something I did it, no matter how much I didn’t want to. I was pleasant, noncompliant, resistant and stubborn as a mule.

You know what?

He went away.

One day, he was just gone.

I knew I’d found the key.

Externalized, Depression suddenly became more pathetic than terrifying. He was so predictable, and so limited. All he had to say were the same things he’d been saying all my life. He was boring. He was like a batty old uncle who must be invited to every family gathering and tells the same interminable stories year in and year out.

He came back, of course, but for shorter and shorter visits at wider and wider intervals.

“Back again, I see,” I’d say. I’d set a place at the table, take out a clean towel, make space in the bed and on the couch. I’d realize I was sliding again and concentrate on eating more regularly, exercising, playing music, putting flowers on the table or maybe scheduling a massage.

I tried to have conversations with him, but Depression had no conversation, just the same tired monologue, mumbling and whining. He was really quite sad. He stopped spending the night and then gradually stopped visiting altogether.

I guess he was no longer getting what he needed from me.

Fear and anxiety are still regular visitors. Things are different here in Maine. I don’t live alone, for one thing. I still play imaginary games, but only in my head. Still, when either fear or anxiety show up, I recognize them. (Anxiety bites her fingernails; I always recognize her hands.) I don’t try to keep them away and I don’t try to hide from them.

I focus on giving them no power. I don’t buy into their catastrophizing. I appreciate they’re trying to keep me safe, poor things. All they can do is make up terrible stories about what might happen and then sit, paralyzed by their imaginings. I know they’re wretched. I wish I could help. I try to be kind — at a distance. They usually don’t stay long.

This experience is the sort of thing I used to hide, but I realize now my struggles are not unique. I’m inspired by the creativity, honesty and vulnerability of other writers. Coping with depression, anxiety and fear is like figuring out how to eat. Every body is different. Everybody needs to find their own path to healing, health and sanity. At times, it’s difficult to break through social expectations and shoulds and make a complete left turn into something creative, intuitive or outside the current norms.

Still, nothing succeeds like success. Turning Depression into an externalized character helped me see I didn’t have to define myself by it. I could choose to set aside that label and all it implies. Once I truly believed I had the power to choose, everything changed.

Sometimes, running away from sudden or passing danger is appropriate. However, running from these chronic spectres dogging my heels has not worked. I can’t get away from them. I can’t avoid or evade. Being chased by anything is fearful. The moment when I stop running, turn around and deliberately go toward whatever threatens me is the moment in which I begin to regain power. Monsters suddenly become mice. My own fear and abdication of power are what made them monstrous. I don’t need to hide. I don’t need to defend. I only need to consistently and patiently demonstrate I will give them nothing they want so they choose to leave me.

It helps when they tell me what to do.

Don’t tell me what to do!

Photo by Senjuti Kundu on Unsplash

All content on this site ©2018

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted

by Jenny Rose | Apr 11, 2018 | Power

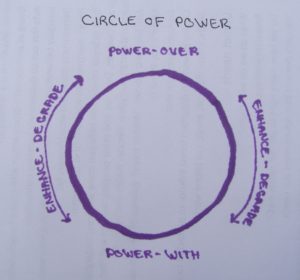

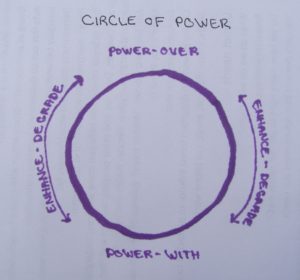

I’ve written before about two positions of power: Power-over (maintaining or creating power inequality) and power-with (maintaining equal power). I’ve thought of this as a complete dichotomy, an either/or lens through which I look at all interactions and relationships, both mine and those around me. Lately, though, I’ve seen two other dimensions in the way we manage power. We are agents of power enhancement or power degradation.

Photo by Ev on Unsplash

Power enhancement and power degradation are the states between power-over and power-with. If we seek to steal the power of others, we begin by sabotaging cooperation, negotiation and equal access to resources — all those things that create communities based in power-with. If our sabotage is successful, power degradation begins. We don’t have complete power-over, not yet, but we are beginning to break down independence, self-sufficiency and the boundaries of others. We are actively working behind the scenes, slowly and subtly corrupting power wherever we can. We might, at this point, have a change of heart and begin fostering behaviors and situations that recreate and enhance power-with, or we might continue with our goal of power-over. Once our goal is attained, we can cease to lurk in the shadows (or under our sheepskin) and come into the spotlight, flushed and triumphant, bloated with stolen power and proud of it.

On the other hand, if we seek to empower others who have been embedded in a power-over dynamic, we begin by managing our own power in such a way that we enhance the power of the disempowered and degrade the power of those maintaining or creating a power-over status quo. Ideally, we don’t give our power away, because that’s a finite resource and leads to burnout and exhaustion. A better way is to use our power to teach, to lead, to support, to legislate and to generally become the wind beneath someone else’s wings. In other words, we appropriately invest our power into teaching others how to discover, reclaim, maintain and manage their own.

An abused child or woman is not going to know how to take care of themselves and function, even if their abuser is magically whisked away. They have to learn. Actually, first they have to unlearn what they already know — all the coping mechanisms that kept them alive in their situation but won’t work well in the wider world — and then they have to learn new skills and behaviors. That takes time, appropriate support from power enhancers and protection from power degraders, at least temporarily, while the victims of power-over learn how to find and reclaim their own power.

The people who live and embody these two intermediate positions of power, enhancers and degraders, are my people — the caregivers. We are the parents and the teachers; the mentors, spiritual leaders, coaches, medical professionals and volunteers who work at shelters, missions, soup kitchens, and out of tents in far-flung places. Interestingly, most of these folks once came from the exterminated middle class. Also interestingly, we see frequent headlines about how some people in this group misuse their position of power and authority in the guise of “helping” others. Shielded by the mask of a power enhancer, they act as power degraders, abusing and exploiting others unchecked, sometimes for decades.

Photo by Cristian Newman on Unsplash

Power enhancement and degradation are not black/white good/bad positions. Many grassroots organizations seek to degrade power in an effort to address our power-over culture and help others reclaim their rightful power. You might say their agenda is to equalize power. The Southern Poverty Law Center is an excellent example. As parents, we might hope to work as power enhancers for our children. As resistance volunteers, we might work against organizations supporting inequality.

It’s important to note our culture doesn’t financially support people in these positions of power particularly well. Teachers strike for better pay. Coaches lay down their lives in bullet-riddled school hallways. Nurses and doctors are vulnerable to addiction, burnout and fractured relationships. Ditto police and firefighters. Compassion fatigue is epidemic. None of these people are millionaires, and some are becoming homeless in places like California as the cost of housing skyrockets. I also note how many of these positions are filled by volunteers. I myself did volunteer fire and rescue work for years, and then animal rescue work and hospice. Red Cross depends on its volunteers. Many healthcare facilities and schools rely heavily on volunteers, as well as sports teams, churches and countless human rights organizations.

Yet it seems to me power enhancers and power degraders are the most important people in our communities. They have the ability to lift others up into integrity and excellence or destroy them. They shape our health, the way we learn and think (or not, sadly), and our spiritual wellness. We trust them with our children, our souls, our secrets and our lives. When they stumble, burn out, fail or waver, we roar with fury, demand justice and retribution, riot and demonstrate, never considering we are the ones who put them in such dangerous, risky, heartbreaking and impossible positions in the first place. We place them on the front lines, put them under constant public scrutiny and pressure and make them responsible for understanding and fixing our increasingly unequal and dysfunctional social power dynamics.

Consider what a professional athlete gets paid, or an entertainer, or a “successful” politician. Compare that to what your children’s teachers are paid, or your local police or fire people, or your nurse practioner or the local softball coach or scout leader. Who has more direct influence in your life and well-being? Who will come help you in the middle of the night, organize community support or assist you with wedding or funeral arrangements?

Here is a graphic demonstrating the circle of power. (Please take a moment to notice the cutting-edge high tech used to generate this graphic. Impressive, yes?) Currently, a power-over dynamic is running the show, and it lies directly across the circle from power-with. We each occupy a place or places along the circle of power, and those places are dynamic and fluid, depending on the daily and even hourly choices we make. Some people spend most of their lives trying to equalize power between people while others work tirelessly to create and maintain unequal power. We all, whether consciously or not, behave in ways that degrade or enhance our own power and the power of others.

Photo by whoislimos on Unsplash

Nobody teaches us about power. Not our parents or schools, and certainly not the media. Yet our inherent rightful power and our need to manage it appropriately and effectively transcends ability level, age, race, sex or socioeconomics. Individual power is apolitical. We all can take the same class, if only we can find teachers.

The problem is, there is no class and our best teachers are exhausted, demoralized, underpaid, underappreciated, overworked and drowning in a crippled education system while others are busy exploiting their positions in order to degrade the power of their students and colleagues. Even if some of the former know something about power management, they’re not in a position to teach anyone else about it. Power management and emotional intelligence skills (which are inextricably intertwined) are not going to show up on a standardized test or entrance exam.

We don’t know how to manage and maintain our power. We haven’t learned it and we can’t teach it. Yet we expect those people who support, protect and serve our communities, all those people who take intermediate roles of power enhancers and degraders, to remain uncorrupted and infallible and spotlessly kind, compassionate, moral, ethical, and just plain GOOD. We give them power and authority blindly, because we can’t recognize appropriate power management from inappropriate either, and expect them to figure it out and do the right thing. We sure as hell don’t know what to do! When that doesn’t happen, we’re angry and we look around for someone to blame, someone or something to scapegoat.

Photo by Talles Alves on Unsplash

How can we expect things to get better if we don’t make some changes?

I suggest we must begin at the beginning, at the foundations, with our children, which means a new paradigm of parenting. Every single adult coming into meaningful contact with a child must be reeducated about the continuum concept and connection parenting. Children need appropriate connection and bonding throughout childhood. If that happens, they learn emotional intelligence and become secure, confident, curious, joyful people who practice power-with as a matter of course, because their own power has never been corrupted or coerced.

How do we freeze everyone in their tracks, wipe their data banks clean and overwrite with better information? How can meaningful change take place if we don’t?

Don’t ask me. I can think about it and write about it, but I have no idea how to tackle such an overwhelmingly impossible task, even if everyone would consent to it, and most won’t. They don’t want to give up whatever power they feel they do have, even if it’s just over their children.

In the meantime, there’s only this small attic room; a grey, chilly spring day outside; and whatever I do or don’t do with my portion of personal power this minute, this hour, this day. I will make choices to enhance or degrade the power of everyone I interact with, including myself. I’ll write, go swimming and pick up birdseed for our empty feeders. I’ll observe others, think about power and try to make mindful choices.

Photo by juan pablo rodriguez on Unsplash

All content on this site ©2018

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted

by Jenny Rose | Mar 22, 2018 | Power

Resilience is “the capacity to recover quickly from difficulties.” (Oxford Dictionaries.) One of the most prevalent difficulties in modern life seems to be the ever-growing cacophony of Those Who Are Offended. I’ve been thinking about this for some time, but last week I read an interview with author Lionel Shriver that brought my own sense of offense to a head. Here’s a quote from that article:

Photo by Syd Wachs on Unsplash

“Shriver … is not the first to argue that the right to give offense is one of the very foundations of freedom of speech. ‘We’re moving in the direction of enshrining the right not to be offended, which is the end of liberty and certainly the end of good books.'”

Oxford Dictionaries defines offense in four ways:

- A breach of law or rule; an illegal act.

- A thing that constitutes a violation of what is judged to be right or natural.

- Annoyance or resentment brought about by a perceived insult to or disregard for oneself or one’s standards or principles.

- The action of attacking someone or something.

Photo by David Beale on Unsplash

The principle of free speech is taking a real battering in the United States. It’s a one-size-fits-all justification for whatever beliefs and ideologies we espouse. Freedom of speech, however, is not absolute. There are limitations around it intended to protect community and individual rights, including the “offense principle,” a restriction based on perceived offense to society. Freedom of speech is a principle that relies on social guidance, which is to say the intelligence and compassion of us, we the people.

This is a problem in a nation where compassion is daily more distorted and taken advantage of and critical thinking and civil discourse are increasingly difficult to come by. Who gets to define “perceived offense to society?”

Everywhere I look, listen and read, I observe people who appear to believe they have a right not to be offended. Freedom of speech grants such people the right to be offensive, as they’re quick to point out, but it’s only a one-way street. Offensive ideas and beliefs are becoming a broad category. Disagreement is offensive (and hateful and bigoted). Certain words, like ‘uterus’ are becoming offensive. Certain pronouns are offensive. Real or perceived exclusion is offensive. A perception of cultural appropriation is offensive. Identity politics of any sort are offensive. Science and evidence-based thinking are offensive. Name any religion or spiritual framework you like — it’s offensive.

When did we become so precious, infantile and entitled that we stopped dealing effectively with being offended?

When did the cancer of selfishness destroy our willingness to consider the needs of those around us?

When were individual distorted perceptions given power over a larger, more common good?

When did disagreement, questions and citing scientific data begin to earn death threats?

Our social, cultural and political landscape is enormously complex, at least at first glance. We’ve become fantastically and gleefully skilled at silencing, deplatforming, invalidating, gaslighting, projection and the fine art of withering contempt. We suffer from an epidemic of what I call Snow White Syndrome. Remember the wretched queen stepmother and her mirror? “Me, me, ME, not you! I’m the fairest, I’m the best, I’m the most victimized, I’m the most downtrodden, I’m the richest, I’m the most offended!”

At first glance, as I said, it’s all so complex. At second glance, it’s all distraction and bullshit. The bottom line is always a power dynamic. Is an individual or group requesting or demanding power-with or power-over?

It really is that simple.

I’m offended every single day. School shooters offend me. Tantruming and pouting politicians offend me. Silencing tactics offend me. Being forced to deal with the sexual fetishes of others offends me. The list goes on and on. You know who’s responsible for dealing with all this offense?

Me.

It’s not your responsibility to refrain from offending me, and it’s not my business to tippy-toe around your delicate sensibilities, either. Many of us try to approach others with kindness and courtesy, but that doesn’t mean we’ll receive either in return. I don’t expect the world to accommodate me. Life is not fair. Equality is an ideal rather than a reality. Inclusivity is not a right.

My rights and needs are as important, but not more important than anyone else’s.

Photo by James Pond on Unsplash

Individuals and groups who lobby to take away the rights of others work from a power-over position. They’re weak and fearful and use violence and intimidation to distract others from their impotence. Individuals and groups who lobby to create more equal power dynamics work from a power-with position. They’re confident and seek authentic connection through information sharing and constructive contribution toward the well-being of all.

Resilience, not priggish rigidity or sheep-like agreement with the prevailing social fashion, always wins the evolutionary jackpot. Resilient life flexes and bends, masters new environments, learns and successfully reproduces, continues. Life that doesn’t dies. Evolution is not personal. It makes no distinctions between a human being and a cockroach. Evolution has a lot of time, millions upon millions of years. The ebb and flow of species on earth is nothing but ripples. Patiently, intelligently, life begins again, over and over, building its complex web.

Photo by Biel Morro on Unsplash

If we can’t figure out how to live in harmony with our bodies, our communities and the earth, we will be deselected. Walking around with a mouth like a pig’s bottom because we’re offended, mutilating and poisoning our bodies, creating sexual pathology that interferes with our ability to reproduce our DNA, wasting our time and energy engaging in idiotic arguments and eradicating education and critical thinking will all lead to deselection, and it should. Such a species is more destructive than constructive to all the other forms of life on this planet.

Difficulties of all kinds are a given. They always have been. Difficulties are the pressures that shape us and make us stronger — or deselect us. If we want to survive, we need to put aside our offended sensibilities and concentrate on the things that contribute to the stuff of life: food, water, shelter, connection, raising healthy children, our physical and mental health and the well-being of Planet Earth. It seems to me that’s enough to be going on with. If we can’t begin to achieve resilience, the debate over who gets to use which bathroom becomes as moot as it is ridiculous.

Resilience can be learned. We foster it by letting go, learning to be wrong, exercising our intelligence, and forming healthy connections so we can learn from one another, figure out how to share power and support one another. Life was never advertised as a free ride. The privilege of life comes with responsibility, demands and competition. Taking offense is not a life skill. Malignant destruction of life, either our own or somebody else’s, is not a life skill. Taking our proper place in the food web and the natural cycles of life and death, on the other hand, is essential if we expect to continue as a species.

Life, in the end, is for those sensible enough to live it, and part of surviving and thriving is resilience. Maybe, if we can get a grip and refocus on what matters, we can learn from the cockroaches, viruses, bacteria, mice, flies, ants, crows, soil organisms and many others that have figured out how to adapt and evolve through every difficulty they encounter.

Offended? Get over it.

Photo by Jonathan Simcoe on Unsplash

All content on this site ©2018

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted

by Jenny Rose | Mar 15, 2018 | Power

Photo by Vladislav M on Unsplash

I’ve always been fascinated by the psychology of survival. I observe that we as a culture are obsessed with heroes and rebels and the endless struggle between archetypal good and evil. Survival kits are becoming a thing in marketing. Preppers write blogs and have TV shows.

Interestingly, our social and cultural world actively inhibits our ability to survive in all kinds of ways. Public school education might be said to be a long indoctrination in anti-survival. We spend hours with our mouths open in front of screens in dark rooms, enchanted by movies and games. Congregations of fans share reverence for comic book characters and the happenings in galaxies far, far away. We debate, criticize and celebrate the way these carefully constructed heroes dress, speak, look, act and collaborate with special effects. We have high expectations of our heroes. We imbue them with nostalgia. We expect our heroes to be just, compassionate, intelligent, interesting, attractive, moral, humorous, strong and poised.

Meanwhile, dangerous events take place in our families; in our workplaces, subways, airports and schools; in our world.

We wait for someone to neutralize the danger, clean it all up, drain the swamp, and make it all fair. We wait for rescue. We turn a blind eye. We do whatever it takes to distract ourselves from uncertainty, fear and our own powerlessness. We watch the beast lumber toward us and deny its presence, deny its existence until we find ourselves in its belly, and then we still refuse to believe.

I’ve been reading author Laurence Gonzales. He’s written several books (see my Bookshelves page). We have Deep Survival and Everyday Survival in our personal collection. Gonzales has made the subject of survival his life’s work. He’s traveled extensively, synthesized studies and research and spent hundreds of hours interviewing people involved with all kinds of catastrophes, both natural and man-made. His books are thoughtful, well-written, extraordinarily well researched and utterly absorbing.

Gonzales uncovers the astounding complexity of human psychology and physiology as he explores why we survive, and why we don’t. He’s discovered some profound and surprising truths.

The best trained, most experienced, best equipped people frequently do not survive things like avalanches, climbing accidents, accidents at sea and being lost in the wilderness. Sometimes the youngest, weakest female has been the sole survivor in scenarios like this. It turns out some of the most important keys to survival appear to be intrinsic to our personalities and functioning, not extrinsic.

Photo by Tommy Lisbin on Unsplash

Gonzales does not suggest, and nor do I, that training, equipment and experience don’t count, just that they’re not a guarantee. In some cases, our experience and training work against us in a survival situation, because we assume a predictable and familiar outcome in whatever our activity is. We’ve made the climb, hike, journey before, and we did just fine. We’ve mastered the terrain and the necessary skills.

Mt. Saint Helen’s had never erupted before. Therefore, all those people who stood on its flanks and watched in wonder failed to grasp that something new and unprecedented was happening. Their inability to respond appropriately to a rapidly changing context killed them. The same thing happens during tsunamis. People are awed and transfixed. They have no direct experience of a tsunami bearing down on them as the water rolls back to expose the sea bed. They don’t react in time.

There’s a model called the OODA loop. The acronym stands for Observe, Orient, Decide, Act. Our ability to move quickly through the OODA loop is directly linked to our ability to survive.

Observation, the ability to be here now, the ability to recognize what is, is something everybody can practice all the time. No special equipment or training needed. What is needed, though, is the emotional and cognitive willingness (consent, if you will) to set aside our distractions, addictions, rigid preconceptions and expectations (often invisible to us, making them even more deadly) and dependence on stimulation. It also requires a mind set of self-responsibility. It turns out movie theatres, schools, concert venues and many other places are not safe. We can debate, deny and argue; protest and rally; scapegoat and write new laws. We are and we will. In the meantime, the reality is we are increasingly unsafe in many public places, and no one has the power to wave a wand and take care of that for us.

It’s up to us to take care of ourselves. That starts with observation.

In my post on self-defense I mentioned situational awareness. Our instructor emphasized that skill as being more important than any other move or weapon. If we see or sense something dangerous in our vicinity, it’s up to us to orient and move to a safer location.

That brings up another very important survival skill: instinct. At this point science cannot measure instinct, but Gonzales’s instinct about getting on a certain plane saved his life once, and many of us have similar stories. As far as I’m concerned, instinct is part of observation. What do we observe? How do we feel about what we observe?

Photo by Wynand van Poortvliet on Unsplash

Our instinct is blunted in all kinds of ways. It’s mixed up with political correctness, including racial profiling. Few of us want to demonstrate discomfort around others for any reason these days. I invariably feel guilty when I react to someone negatively, even if my reaction is entirely private. It’s bad and wrong to judge, to cross the street to avoid somebody. It’s ugly and hateful.

Additionally, I’m a woman and I’m highly sensitive, which makes me particularly attuned to body language, voice inflection and all the clanging (to me) subtext of communication beneath whatever words are spoken. I can’t prove my intuition. I can’t demonstrate it logically. I have no wish to diminish or disempower others. I’m not a bigot. All people have energy and sometimes it’s foul. I reserve the right to move away from it. If that makes me hateful, woo, dramatic or hysterical, so be it. I’m accomplished in the art of noncompliance, but many are not.

If we only see what we expect to see, we aren’t observing. If we fail to see what we’re looking at, we’re not observing. If we can’t take in the whole picture, we’re not observing. If we look for something instead of at everything, we’re not observing. We’ve already broken the OODA loop.

Observing and orienting mean coming to terms with what we see. The plane is down. Our ankle is broken. We’re lost in a whiteout blizzard off the trail. We can’t decide how we’re going to survive if we’re unable to accept and orient to what is.

As a young woman, I did fire and rescue work. I was an IV-certified EMT, and I learned in those days that panic, fear and despair are killers. They’re also highly contagious. People who survive lock those feelings away to deal with after they’re safe again. Gonzales found, amazingly, some people will sit down and die, though they have a tent, food and water in the pack on their back. They just give up.

I also learned that the hysterical victims are not the ones most likely to die in a multiple trauma event. They demand the most attention, certainly, but it’s the quiet ones who are more likely to have life-threatening injury and slip away into death. The screamers and the drunks, the ones blaming, excusing and justifying, are frequently the cause of the accident and retard rather than assist in the survival of themselves and those around them.

On the other hand, strength, determination and calm are also contagious. If just one or two people in a group keep their heads and take the lead, chances for survival begin to increase for everyone.

When I was trained as a lifeguard and swimming teacher, I learned something that’s always stayed with me.

You can’t save some people. It’s possible to find yourself in a situation where, in spite of your training and best efforts, the victim is so combative or uncooperative, or the circumstances so impossible that the choice is between one death or two. This fact touches on my greatest impediment to survival, which, ironically, is also one of my greatest strengths.

My compassion and empathy mean I frequently put the needs of others before my own. I do it willingly, gladly, generously and out of love. It’s one of my favorite things about myself, and it’s also one of my most dangerous behaviors.

Consider a scene many of us are metaphorically familiar with. Someone nearby is drowning. They’re screaming and thrashing, weeping, begging to be saved. We throw them a rope so we can pull them out. They push it away and go on drowning because the rope is the wrong color. Okay, we say, anxious to get it right and stop this terrible tragedy (not to mention the stress-inducing howling). We throw another rope, but this one is the wrong thickness. It, too, is rejected, and the victim, who is remarkably vocal for a drowning victim, continues to scream for help.

Photo by Lukas Juhas on Unsplash

On it goes, until the rescuer is exhausted, desperate, deafened and feeling more and more like a failure. Meanwhile, the “victim” goes on drowning, loudly, surrounded by various ropes and other lifesaving tools. We, as rescuer, are doing every single thing we can think of, and none of it is acceptable or adequate. In our frantic desire to effect a rescue at the cost of even our own lives, we’ve ceased to observe and orient. We’re not thinking coolly and calmly. We’re completely overwhelmed by our emotional response to someone who claims to want help.

The survivor in this picture, my friends, is not the rescuer. The so-called victim is the one who will survive. If they do grudgingly accept a rope and are successfully pulled out of the water, they immediately jump back in.

The will to survive is an intrinsic thing, and I can’t give or lend mine to someone else. People who can’t contribute to their own survival, and we all know people like that, are certainly not going to contribute to mine, and some will actively and intentionally pull me down with them, just because they can.

I don’t have to let that happen, but in order to avoid it I need to be willing to see clearly, accept what I see, cut my losses and act in my own behalf. Real life is not Hollywood, a comic book or virtual reality. It’s not my responsibility to be a savior, financially, emotionally, sexually or in any other way. The word survivor does not and cannot apply to everyone.

It’s a harsh reality that doesn’t have much to do with being politically correct or approval and popularity, and most people have trouble facing it, which will inhibit their survival if they ever find themselves in an emergency situation.

Gonzales covers this at some length in Deep Survival, and he rightfully points out that compassion and cool or even cold logic are not mutually exclusive. People in extreme situations sometimes have to make dreadful decisions in order to live, and they do. A compassionate nature that does what must be done may buy survival at the cost of life-long trauma. Ask any combat veteran. This is the side of the story the Marvel Universe doesn’t talk about. Survival can be primitive, dirty and gut wrenching. Sending blue light and thoughts and prayers are not the stuff of survival.

Clear orientation leads to options and choices. Evaluating available resources and concentrating on the basics of survival: water, food, shelter, warmth, rest and first aid are essential. Thinking coolly and logically about what must be done and breaking the task into small steps can save people against all odds.

Sometimes, death comes. Eventually, we all reach our last day. In that case, there’s no more to be said. Yet the mysterious terrain on the threshold between life and death is remarkably defining. I wonder if perhaps it’s the place where we learn the most about ourselves.

Photo by Andrew Neel on Unsplash

I’ve known people who stockpile weapons and ammo, bury gold in bunkers, build off-grid compounds and obsess about survival equipment and bug-out bags. Many wilderness schools teach basic and advanced survival techniques. Some folks put all their financial resources into prepping for catastrophe and collapse. I’m nervous about the state of the world on many levels myself, so I understand, but I can’t help thinking that investing in a story about living in a guarded, fully-equipped compound is not much better than investing in a story that water will continue to run from faucets, a wall socket will deliver electricity and grocery shelves will hold food, forever and ever, amen.

After reading Gonzales, I’m considering maybe simply living life is the best preparation for survival. Trusting my instinct; learning to manage my power and feelings; being aware of the limitations of my experience, expectations and beliefs are all investments in survival. Simply practicing observation is a powerful advantage. I don’t have money to spend on gear and goodies I might or might not be able to save, salvage or retain if things fall apart. The kind of investment that will keep me alive is learning new skills, staying flexible and adaptive, developing emotional intelligence and nurturing my creativity. No one can take those tools away from me and I can use them in any scenario.

We’re born with nothing but our physical envelope. Ultimately, perhaps the greatest survival tool of all is simply ourselves, our wits and our will.

All content on this site ©2018

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted