by Jenny Rose | Jul 26, 2018 | Connection & Community, Emotional Intelligence, Shadows

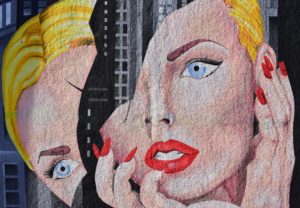

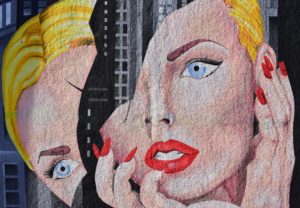

I looked up the word “denial” to find a quick definition as a starting point for this post. Fifteen minutes later I was still reading long Wiki articles about denial and denialism. They’re both well worth reading. I realize now the subject of denial is much bigger than I first supposed, and one little blog post cannot do justice to its history and scope.

Photo by Ian Espinosa on Unsplash

I wanted to write about denial because I keep tripping over it. It seems to lurk in the background of every experience and interaction, and it’s nearly always accompanied by its best buddy, fear. I’ve lately made the observation to my partner that denial appears more powerful than love in our culture today.

I’ve written before about arguing with what is, survival and being wrong, all related to denial. I’ve also had bitter personal experience with workaholism and alcoholism, so denial is a familiar concept and I recognize it when I see it.

I see it more every day.

I was interested to be reminded that denial is a useful psychological defense mechanism. Almost everyone has had the experience of a sudden devastating psychological shock such as news of an unexpected death or catastrophic event. Our first reaction is to deny and reject what’s happening. Elisabeth Kubler-Ross identified denial as the first of five stages of psychology in a dying patient. Therein lies the distinction between denial as part of a useful and natural cycle and denial as a permanent coping mechanism. In modern psychology denial is followed by other stages as we struggle to come to terms with a difficult event. We (hopefully) move through the stages, gathering our resources to cope with what’s true and coming to terms with the subsequent changes in our lives.

Denialism, on the other hand, is a “choice to deny reality as a way to avoid a psychologically uncomfortable truth” (Wikipedia). For some, denial is an ideology.

In other words, denialsim is all about fear, fear of being wrong, fear of change, fear of painful feelings, fear of loss of power, fear of one’s cover being blown. This is why some of the most rabid and vicious homophobes are in fact homosexual. Unsurprisingly, projection and gaslighting are frequently used by those who practice denialism.

I’ve no doubt denial is an integral part of the human psyche. I never knew anyone who didn’t have a knee-jerk ability to deny. I do it. My partner does it. My friends and family do it. My partner and I have a code phrase: “I’m not a vampire,” that comes from the TV series Angel in a hilarious moment when a vampire is clearly outed by one of the other characters. He watches her put the evidence together: “… nice place… with no mirrors, and… lots of curtains… Hey! You’re a vampire!” “What?” he says. “No I’m not,” with absolutely no conviction whatsoever. It always makes us giggle. If Angel is too low-brow for you, consider William Shakespeare and “the lady doth protest too much, methinks.” Denial is not a new and unusual behavior.

Photo by NASA on Unsplash

The power of denial is ultimately false, however. Firstly and most obviously, denial does not affect the truth. We don’t have to admit it, but truth is truth, and it doesn’t care whether we accept it or not. Secondly, denial is a black hole of ever-increasing complications. Take, for example, flat-earthers. Think for a moment about how much they have to filter every day, how actively they have to guard against constant threats to their denialsim. Everything becomes a battlefield, any form of science-related news and programming; many types of print media; images, both digital and print, now more widely available than ever; and simple conversation. I can’t imagine trying to live like that, embattled and defensive on every front. It must take enormous energy. I frankly don’t understand why anyone would choose such hideous complications. It seems to me much easier to wrestle with the problem itself than deal with all the consequences of denying there is a problem.

Maybe that’s just me.

It seems our denial becomes more important than love for others or love for ourselves. It becomes more important than our integrity, our health, our friends and family, loyalty, and respect or tolerance. Our need to deny can swallow us whole, just as I’ve seen work and alcohol swallow people whole. Denial refuses collaboration, cooperation, honest communication, problem solving and, most of all, learning. Denialism is always hugely threatened by any attempt to share new information or ask questions.

Photo by Jonathan Simcoe on Unsplash

Denial is a kind of spiritual malnutrition. It makes us small. Our sense of humor and curiosity wither. Fear sucks greedily on our power. We become invested in keeping secrets and hiding things from ourselves as well as others. We allow chaos to form around us so we don’t have to see or hear anything that threatens our denial.

This is not the kind of fear that makes our heart race and our hands sweat. This is the kind of fear that feels like a slamming steel door. It’s cold. It’s certain. We say, “I will not believe that. I will not accept that.”

And we don’t. Not ever. No matter what.

A prominent pattern of folks in denial is that they work hard to pull other people into validating them. Denial works best in a club, the larger the better. The ideology of denialism demands strong social groups and communities that actively seek power to silence others or force them into agreement. Not tolerance, but agreement. This behavior speaks to me of a secret lack of strength and conviction, even impotence. If we are not confused about who we are and what we believe, there’s no need to recruit and coerce others to our particular ideology. If you believe the earth is flat, it’s fine with me. I’m not that interested, frankly. I disagree, but that’s neither here nor there, and I don’t need you to agree with my view. When I find myself recruiting others to my point of view, I know I’m distressed and unsure of my position and I’m not dealing effectively with my feelings.

I’ve written before about the OODA loop, which describes the decision cycle of observe, orient, decide and act. The ability to move quickly and effectively through the OODA loop is a survival skill. Denial is a cheat. It masquerades as a survival strategy, but in fact it disables the loop. It keeps us from adapting. It keeps us dangerously rigid rather than elegantly resilient.

Some people have a childlike belief that if something hasn’t happened, it won’t, as in this river has never flooded, or this town has never burned, or we’ve never seen a category 6 hurricane. Our belief that bad things can’t happen at all, or won’t happen again, pins us in front of the oncoming tsunami or the erupting volcano. It allows us to rebuild our homes in places where flood, fire and lava have already struck. We ignore, minimize or deny what’s happening to the planet and to ourselves. We don’t take action to save ourselves. We don’t observe and orient ourselves to change.

Some things are just too bad to be true. I get it, believe me. I’m often afraid, and I frequently walk through denial, but I’m damned if I’ll build a house there. The older I get, the more determined I am to embrace the truth. I don’t care how much pain it gives me or how much fear I feel. I want to know, to understand, to see things clearly, and then make the best choices I can. It’s the only way to stay in my power. I refuse to cower before life as it is, in all its mystery, pain and terrible beauty.

Ultimately, denial is weak. I am stronger than that.

Photo by Joshua Fuller on Unsplash

All content on this site ©2018

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted

by Jenny Rose | May 31, 2018 | Connection & Community, Emotional Intelligence

A couple of years ago my adult son and I had a heated exchange during which I asked him exactly what he wanted from me. It was a useful question. For a moment we stopped being adversaries while he thought about it. “Umm, I don’t know. What I’ve always had, unconditional love, I guess.”

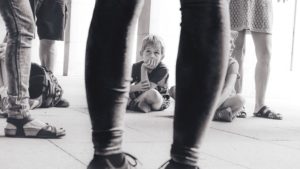

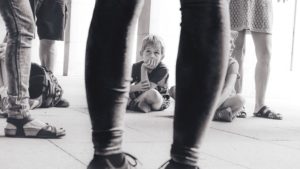

Photo by Jordan Whitt on Unsplash

That moment has stayed with me, because as I asked the question I realized I really didn’t know, and I was both curious and interested. What does a fully emancipated twenty-something-year-old man honestly want from his mother? It was the first time it ever occurred to me to ask either of my sons what they wanted from me at any age or stage.

I never thought of anything except what I wanted to give them.

I’ve been reading about emotional labor recently, which leads me irresistibly to the concept of benign neglect.

Emotional labor is the often invisible process of managing feelings and their expressions as part of a job or relationship. The idea often comes up as part of the ongoing discussion about gender roles and equality, but I’m thinking about it in a slightly different context.

Benign neglect is a term that originated out of city planning politics and now also describes an attitude of inaction regarding an unproductive situation one is commonly held to be responsible for.

I’ve written before about pleasing people, boundaries and reciprocity. Emotional labor is embedded in all of these, and it’s been a primary dysfunction in my relationships over the years, though I haven’t had any language or distinction about my experience of it until recently.

If you Google emotional labor you find definitions, descriptions, assertions about the disproportionate burden of emotional labor on women, and the powerful but invisible expectations regarding who is responsible for emotional labor in any given situation. What you don’t find is discussion about how to make visible and support the vital aspect of emotional labor in community, jobs and families. The discussion stops at equal rights.

Equal rights is an important discussion to have, but in the meantime we’re dealing with families, friends and jobs today and emotional labor is an inescapable need right now.

I think of emotional labor as glue. You don’t see it, but if it’s missing everything falls apart. If it’s applied carefully it holds things together. If we don’t keep a calendar and glance at a clock now and then, we can’t manage our lives. Either we learn to cope with appointments, deadlines, commitments, grocery lists and feelings ourselves or we rely on someone else to do it for us. Part of adulting is learning emotional labor.

Photo by freddie marriage on Unsplash

I’m a button sorter by nature, and I take a lot of pleasure in being organized. My life works better when I take the trouble to be effective and efficient, and it gives me pleasure to share with my loved ones the benefits of thinking and planning ahead and taking care of business. Remembering special dates, buying tickets, planning for bake sales and decorating for the holidays have all been offerings symbolizing my love and willingness to provide support to my family, along with the daily activity of simply showing up in my relationships.

I said that recently to my partner — “this is me showing up in the relationship.” He had no idea what I meant.

I was staggered. What do you mean, what do I mean? You know, asking if you slept well because you didn’t the night before. Or inquiring about the status of that headache you complained about yesterday. Or asking you what’s in your attention and what you’d like to do today. Listening. Sharing. Showing concern. Demonstrating I appreciate you enough to be present. Reminding you that we’re almost out of cat litter. Thanking you for patching the mousehole in the cupboard. Showing up in the relationship!

Photo by Ester Marie Doysabas on Unsplash

Yeah. Aka emotional labor.

He listened and shrugged. I didn’t describe anything he could relate to. He lives his life with me without showing up or not showing up. He just does what he does, says what he says, is interested in what he’s interested in. He doesn’t check in with himself every day to be sure he “showed up” in a way that reassures me of his ongoing affection and caring.

I do.

I’ve thought a lot about this since that conversation. I’ve been conscious of a huge annoyance and, underneath that, amusement.

All my emotional labor is completely unneeded. He never asked me to do it. It’s not useful. It’s invisible to him.

This made me wonder if that’s been true in all my other relationships as well, including with my kids, historically and presently.

That’s not right, though, because I’ve been with some real man-babies. My husband once called me at work because the baby had a soiled diaper. (Okay, it was a real blow-out, but still!) Then there was the guy who wanted a dog to fish with, but didn’t want to walk it, poop scoop after it or stay up all night on July Fourth holding its paw because it was terrified of firecrackers and invariably went into seizures (it had epilepsy).

And then there were the kids. There’s no question at all that raising kids takes a lot of emotional labor. It’s both needed and required.

Photo by Chris Barbalis on Unsplash

I guess I just got into the habit. Emotional labor has been my offering, my contribution, in every relationship. I’m good at it. Until very lately, I never considered reciprocity and I had no definition for emotional labor. I just thought of it as being a good woman.

When my son said he wanted what I’d always given, unconditional love, I had a moment of real satisfaction. I made so many mistakes, but at least I did that right. On the other hand, can those two simple words ever encompass the totality of heart, pain, frustration, energy, loyalty and years they represent? Unconditional love. That’s all.

Right.

I was with a man for a long time who had no interest in emotional labor. Once he had me hooked, he was never decisive, confident or clear again. He initiated no physical contact. He resisted making any plans. He made no effort to develop rituals, routines or regular check-ins. His job was stressful, he had some sleep and health issues, and his favorite excuse was “I forgot.” I gave and he withheld.

Eight years later (slow learner) burned-out, anguished and desperate, it occurred to me to wonder what would happen if I. Just. Stopped.

So I did. I stopped e-mailing. I stopped calling. I made plans without him. I let go of all my expectations and started trying to glue myself back together. I worked, took care of my own responsibilities, enjoyed time with friends and family and went on with my life. I set down all that emotional labor and walked away from it.

Guess what happened?

He floated away.

I’d essentially had an eight-year relationship with myself.

He did eventually (weeks) notice I wasn’t around any more and got in touch, mildly puzzled and reproachful. I was casual and said I’d been busy.

He told me he didn’t feel like he was getting the attention he needed from me. We were sitting in his car at the time. I’ll never forget it.

Until now, I’ve never put that experience in context with all my other relationships. After my recent conversation with my partner about showing up in the relationship, I changed my behavior. I stopped worrying about “showing up” every day. I’ve engaged with my own needs, daily tasks and schedule. I enjoy our time together, but I’ve stopped trying to make it happen. I switched my focus to making sure I show up for myself every day.

What I’ve learned from all this is emotional labor is real and largely unconscious. Many of us give our lives to it. I’ve also learned it’s a choice. When it remains invisible and undefined and we’re operating out of unspoken cultural expectations, we become unconscious of much of our decision-making and motivation. Our desire to be a “good” wife, mother, daughter, lover, sister, whatever, becomes all-powerful and we throw ourselves into it without ever thinking about whether that’s what others want and/or need from us. We don’t consider asking for help or professional support if we’re caregivers. In fact, we feel hurt when our emotional labor of worrying, for example, is not received with gratitude and appreciation! If whoever we’re connected with does want our emotional labor and provides none themselves, we don’t notice. We just work harder.

This is where benign neglect comes in. Benign neglect is an attitude of inaction regarding an unproductive situation one is commonly held to be responsible for, remember? The culture may hold us to be responsible for a lot of things, but that doesn’t make it true.

What if we challenged the “commonly held” belief that all emotional labor is our job in any given relationship? What if we decided it’s not our responsibility, in addition to not being useful, to worry, fuss, organize or manage the feelings of the people around us? What if we took back our power to choose?

Photo by Bruno Nascimento on Unsplash

If I had stopped worrying about doing laundry for my teenagers, or insisting on family mealtimes, or keeping track of their schedules, what then? The sad truth is I was afraid people would think I was a bad mother. I knew I would think I was a bad mother. The kids didn’t do those things for themselves, so I had to do it in order to demonstrate my love, commitment and competence. What kind of a mother lets her kids wear dirty socks?

I didn’t consider the difference between organizing schedules for toddlers and organizing two big, smart, capable boys who saw no reason to bother themselves with boring things like schedules, grocery lists and clean socks. I was so busy demonstrating my feelings, especially my love for them, I never stopped to wonder if they were learning to express their feelings. I didn’t ask.

It annoys me that only now am I seeing ways in which I could have been a much more effective parent, partner, daughter and sister.

At bottom, I don’t think emotional labor is about equal gender rights at all. I think it’s about choice, and choice is about power. We can’t choose if we don’t recognize there is a choice, we can only stumble forward blindly, doing our best with what we think the rules and expectations are, external and internal, until, overburdened, overwhelmed and exhausted, we fall down and don’t get up again. Meanwhile, the people we love, the ones we’re doing all this labor for, are not saved by our labor. Kids grow up, have car accidents and bad relationships, choose crappy diets, fall into addiction, catch an STD. Parents grow old, have health problems, and become dependent. Siblings, friends, lovers and mates are not assisted by our worry, our ability to manage their feelings or our “showing up” in the relationship. All our loved ones might be a great deal better off if we hadn’t taken on all the emotional labor ourselves, because when life happens, as it inevitably does, they lack the skills we never let them learn because we were so busy being good women.

Also, when was the last time you were thanked for all your emotional labor? (What do you mean, “showing up” in the relationship?)

You gotta love the irony of the whole thing.

What would my relationships look like if I kept my emotional labor in balance with the labor of those I’m connected to? What if I could be more like my partner and trust that my affection and love for him (and others) are communicated and understood without such deliberate emotional labor? He just naturally demonstrates his feelings for me in our day-to-day life without all this effort and trying. What if I relaxed and redefined what being a “good woman” means?

I’m going to find out.

Photo by Ryan Moreno on Unsplash

All content on this site ©2018

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted

by Jenny Rose | Oct 26, 2017 | A Flourishing Woman, Mind

I went to the dentist last week. I spent the usual hour with the hygienist and then the dentist breezed in to give me four or five minutes of exam, comment, teaching and friendly conversation. Thankfully, I don’t require more than this, as my teeth are in excellent shape. In the course of those few minutes, I used the term “permaculture,” and he asked me what it was. I gave him a brief answer, and on the way out the hygienist said I had a “high dental IQ.”

“She has a high IQ, period,” he responded as he left.

I almost got out of the chair and went after him to explain that I’m the dumb one in the family, and certainly don’t have a high IQ.

As I’ve gone about life since then, I’ve thought a lot about that interaction. I’ve also been feeling massively irritated, isolated and discouraged. This morning I woke out of a dream of being in a closet groping for my gun, my knife, even my Leatherman, absolutely incandescent with rage, because a man outside of the closet was having a dramatic and violent meltdown, intimidating everyone present because of something I’d said or done that he didn’t like.

I wasn’t intimidated. I was royally pissed off.

When I had my weapons assembled, I stormed out of the closet and came face-to-face with a clearly frightened woman who was wringing her hands and making excuses for the behavior of the yelling man. I screamed into her face that he could take his (blanking) opinions and shove them up his (blanking blank) and unsheathed my knife, not because of her, because of HIM.

I woke abruptly at that point and thought, I’m not depressed, I’m MAD!

Photo by Nicole Mason on Unsplash

While I showered and cooked breakfast I sifted through IQ and conformity and cultural and family rules, economic success and failure, work, invalidation and silencing and keeping myself small. I thought of how pressured I’ve always felt to toe the line, be blindly obedient, follow the rules, ask no questions and be normal. Normal, as in compliant, and refraining from challenging the multitude of life’s standard operating procedures that “everyone knows.” Normal, as in not daring to resist, persist, poke, peel away, uncover. Normal, as in never, NEVER expressing curiosity, a thought, an experience, a feeling or an opinion that might make someone uncomfortable. Normal, as in never admitting that the way we’re supposed to do things doesn’t always work for me, and frequently doesn’t appear to work for others, either. I slammed around the kitchen, turning all this over in my mind, letting the bacon burn, and finally pounced on a keystone piece to write about.

What does it mean to be smart? Why do I feel like a lying imposter when someone makes a casual comment about my IQ? Why is IQ even a thing? Why does so much of my experience consist of “sit down and shut up!”?

Intelligence is defined on an Internet search as “the ability to acquire and apply knowledge and skills.” Please note the absence of any kind of test score in that definition. Likewise, there’s no mention of economic status, educational status or social status. Also, this definition says nothing about intelligence as a prerequisite for being a decent human being.

The definition takes me back to the playing field in which I wrote last week’s post on work. Here again we have a simple definition for a word which is positively staggering under assumptions and connotations.

Fine, then. I’ve explored what work means to me. What does intelligence mean to me?

Intelligence means the ability to learn, unlearn and relearn. Good learners do not sit down and shut up. We question, and we go on questioning until we’re satisfied with answers. We try things, make hideous mistakes, think about what went wrong and apply what we learned. We don’t do the same thing over and over and expect a different result. We exercise curiosity and imagination. We pay attention to what others say and do and how it all works out. We pay attention to how we feel and practice telling ourselves the truth about our experience. After a lot of years and scar tissue, we learn to doubt not only our own assertions, beliefs and stories, but everyone else’s as well. We practice being wrong. We become experts in flexible thinking. We adapt to new information.

We give up arguing with what is.

Intelligence endures criticism, judgement, abuse, taunts, threats, denial and contempt. It’s often punished, invalidated and invisible. Intelligence takes courage.

Photo by Cristina Gottardi on Unsplash

Intelligence is power. It does not sit at the feet of any person, ideology, rule or authority and blindly worship. It retains the right to find out for itself, feel and express its own experience, define its own success, speak its truth in its own unique voice, and it remembers each of us is limited to one and only one viewpoint in a world of billions of other people.

Intelligence is discerning the difference between the smell of my own shit and someone else’s.

For me, intelligence is a daily practice. It’s messy and disordered and fraught with feeling. It means everything is an opportunity to learn something new. Everything is something to explore in my writing.

I have no idea what my IQ is, and I don’t much care. I’m sick and tired of all the family baggage I’ve carried around about who’s smart and who isn’t and how we all compare. Honestly. What am I, 10 years old? Enough, already.

I’m also fed up with being silenced, and in fact I’ve already refused to comply with that, as evidenced by this blog. I understand a lot of people don’t want to deal with uncomfortable questions. Too bad. Those folks are not going to be my readers. It’s not my job to produce sugar-coated bullshit that can’t possibly threaten or disturb anyone.

So there it is. The practice of intelligence.

Photo by frank mckenna on Unsplash

All content on this site ©2017

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted

by Jenny Rose | Jun 29, 2017 | Connection & Community, Emotional Intelligence, Shadows

I’m getting ready to turn over the manuscript of my first book to a developmental editor. Getting ready means I’m doing one final read through and combing out overused words and phrases using the search (and destroy) feature in my word processor. Over the months and years I’ve been working with my book and mastering the mechanics of writing, I’ve learned a lot about language and my own personal tics and patterns. The biggest problem I’ve found in my writing is unconsciously using passive voice.

Photo by freddie marriage on Unsplash

On the face of it, the process of cleaning up a manuscript is straightforward and occasionally mind-numbingly tedious. Looking at 4000 plus occurrences of the word ‘was’ throughout 1000 plus pages is not filled with giggles and takes a long time. I entertain myself with battleship noises every time I eliminate ‘was’, ‘were’, ‘had’, or ‘have’. I also come up with amusing similes for the process. My favorite is that editing is like combing nits out of a child’s hair.

On the plus side, this practice opens up a lot of time in which to notice my unconscious language patterns and think about how word choice reflects my choices in every other aspect of life. Editing word by word in this way is also a great habit breaker. When I write ‘had’ or ‘have’ now I notice it.

In the past, I’ve also overused ‘gently’, ‘lightly’, ‘quietly’, ‘a little’, ‘went’ (that’s a common one), and ‘softly’. As these patterns become visible to me, I ask myself with some annoyance, why not ‘fiercely’, ‘loudly’, ‘a LOT’ or ‘strode, galloped or dashed’?

I’ll tell you why not. Because I’m female and my culture has successfully taught me to make myself small. That lesson is so central and ubiquitous I’ve only recently been able to identify it and organize resistance. The message is impossible to see until you see it, and then you can’t unsee it.

Do you know the old French fairy tale of Bluebeard? A serial wife killer instructs his latest victim to refrain from opening a door in his castle, the door a particular little key opens. Then he leaves her alone with his keys (of course). In his absence, Bluebeard’s young wife and her sisters explore the castle, opening every door, and (naturally) the wife is persuaded there’s no harm in just peeking behind that last forbidden locked door. In the room they discover a row of headless bodies and a pile of heads belonging to Bluebeard’s previous wives. They exit the room (as you might imagine) and conspire to pretend they never unlocked the door. The only problem is the little key that unlocked the door begins weeping drops of blood and nothing they can do makes it stop. Bluebeard returns, discovers the infraction, and … I won’t tell you what happens, because different versions of the story end differently. This fairy tale is embedded in my own book. The point is, once some things are understood and seen, they can’t be unseen. There is no going back.

So, consider this commandment with me: Make Yourself Small.

Photo by Hailey Kean on Unsplash

- Adhere to the arbitrary cultural ideal of acceptable attractiveness. If you can’t, hate your body, torture it, starve it, distort it, color it, shave it and beat it into compliance. Make yourself conform.

- Let media, social media, experts, professionals, your favorite news channel or radio host, your religious leader, your parents, or the men in your life tell you what to believe and what to think. Don’t you bother your pretty little head trying to understand anything.

- Make your sexuality, passion and lust small. In fact, make them invisible (you slut).

- Make your intelligence nonthreatening.

- Tame your creativity.

- Don’t ask questions. Don’t search for clarity and truth. Don’t do your own research. Restrain your curiosity.

- If you must have needs, make them as infinitesimal as possible. Your needs are dust in the wind compared to the convenience, habits and preferences of others.

- Be silent! You are disqualified from having an opinion. Don’t tell your truth. Others are speaking. Censor your voice. Don’t make anyone uncomfortable.

- Capture, restrain, cage, shackle, chain and abandon your dreams. Who do you think you are?

- Deny, belittle, smother and minimize your feelings. Control yourself!

- Shame on you! Cringe, cower, hide your head! You’re bad and wrong!

- Be self-contained. Be self-sufficient. Don’t take up too much space. Move lightly. Don’t spend too much money. Don’t be too dramatic. Don’t be too sensitive. Don’t order dessert. Don’t attract attention. Don’t breathe too much air. MAKE YOURSELF SMALL!

You get the idea, I’m sure. This list goes on and on. The message is everywhere, and we’re all affected. It cuts across social, racial, economic, political and gender divides. Failure to toe the line, whatever that line is, results in harsh social and professional consequences, up to and including death. Show me a headline and I’ll pick out this theme. I trip over it a dozen times a day in my own life. Spend five minutes on Facebook reading any thread on any subject and you’ll find this underlying message.

Photo by James Pond on Unsplash

The surrounding cultural mandate to make ourselves small is toxic, but it’s not the heart of the problem. The heart of the problem is our internalization of the mandate before we’re even aware of it, and then it becomes so woven into the fabric of our experience we no longer discern it.

Ironically, stubbornly pursuing my passion for writing and my determination to be bigger is what reveals to me the outlines of my own self-sabotage. My habit of making myself small has trickled all the way down to the words I choose. Editing my manuscript has become editing my thoughts and choices, and noticing the words I write and think in helps me notice my feelings.

My feelings contain a lot of fury and a lot of rebellion, far more than I was aware of when I created this blog last summer. Minor friction with my partner about planning a day or how we utilize counter space taps into a deep vein of lifelong rage and pain about allowing and participating in my own repression and oppression. I have systematically colluded in my own erasure. I’ve agreed to make myself small. I’ve agreed to abdicate my power.

No more. I opened Bluebeard’s chamber, and saw what it contained. The key that unlocked the door was writing, and I’m deleting all the blood-stained words that make my art small. If I fail as a writer, I’m not going to do it softly, gently, lightly or a little. I’m going to do it thunderously, monumentally and profoundly.

It’s time to make myself big.

Photo by Stephen Leonardi on Unsplash

All content on this site ©2017

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted

by Jenny Rose | Apr 20, 2017 | Power

I came across a prayer to Baba Yaga recently. I’ve spent a lot of time with Baba Yaga, who is a supernatural female figure out of Slavic European folklore. I’ve told stories about her for years, and she’s an important character in my book. She’s a powerful life-death-life-death figure and has many names, among them Storm Raiser, Primal Mother, Lady of Beasts and Mother of Witches. In spite of our long acquaintance, I’ve only lately begun to love her.

Photo by ivan Torres on Unsplash

Sometimes I think the most important thing to understand about life is power. It structures every single relationship, most of all our relationships with ourselves. Power creates wars, cults, murderers, abusers, tyrants, rebels and perhaps angels.

I believe we have a great longing for our individual mislaid power, such a longing that we’ve lost track of what it is or how to recognize it in our hunger and desperation. I don’t know how else to explain our mindless obedience to the media, to our culture, to our religions, to the almighty “they” who instruct us how to live, how to eat, what to believe, how to look, how to buy and how to be.

At this time in my life, and at this time in my country’s history, I cling to Baba Yaga, because she represents sanity in a world becoming more insane by the day. The prayer reminds me of what true female power is — and is not.

True female power wastes no time on despots and bullies who conceal their fear and impotence behind dishonesty and the willingness to use force. It’s not her business to prop them up. They have nothing she needs and they’re not worth her attention, for they shall not endure.

True female power is real. It’s authentic. It’s not bound by chains of political correctness, manners, fear or ideology. A woman in her authentic power is, according to need and whim, a child, a wild woman, a bitch, a seductive temptress, a crone, and a creature of magic. Obedience and compliance are not in her nature.

True female power seeks the hidden thing, within and without. She pares away layers, stories, masks, facades, dreams, visions, expectations, and shoulds. She’s a persistent poker, prier and meddlesome busybody in holey tennis shoes. She opens drawers, boxes and jars, looks behind forbidden doors and never stops asking questions. She refuses to shut up, close her eyes or pretend, and views everything by the stark light of a fiery skull without flinching. She doesn’t need anyone to agree with her, and she doesn’t need everyone to agree with her. She doesn’t argue with what is. The truth cannot escape her.

True female power doesn’t prostitute for love and validation. Baba Yaga eats sulfur to make her farts more momentous and fertilizes her body hair to make it grow more abundant. She’s hairy legs and iron-tipped fingers and teeth sharpened on bones. She takes a lover when she feels like it, but she kicks him out of her bed before dawn and doesn’t offer breakfast. Her body is not for sale, her hair is the color it wants to be, and she has no use for a painted mask over her face.

True female power is a teacher of magic. She teaches the sorting of one thing from another, cleansing, lighting a fire, the alchemy of cooking. She’s the power of the cauldron, the cup, the womb and the growing seed. She’s the wisdom of bone and blood, seed and water, life and death. A woman in her authentic female power learns to feed and nurture the magic of her intuition and creativity. She knows they are the most priceless jewels she will ever have.

True female power feels huge, deep feelings of rage, grief, joy and lust. When fear accosts a woman in her power, she spits in its eye and knocks it down on her way forward. An authentically powerful woman knows how to cause earthquakes with her dance, bring rain with her tears, melt rocks with her passion and sow stars with her joy. She allows no one to make her small.

True female power expresses all her fine feelings. She shrieks, curses, cackles, stomps, grumps, slams and mutters. She will not be silent. She stays up all night drumming and dancing if the mood takes her, and sleeps all day when she wants. She collects secrets, stories, marbles and insults with equal enjoyment. In fact, she says and does exactly what she wants to do and say.

(Yes, I said marbles.)

True female power is ancient and enduring. It’s coarse silver hair, aching bones, pearly stretch marks, lumpy thighs, scars and wrinkles and cracks and crevices. A woman in her power bleeds, first red and then the invisible silver blood of wisdom that arrives when the children of her body have become ghosts living only in her memory. A woman in her full authentic power smiles kindly on the young and beautiful, because they are not yet capable of her wisdom.

Photo by Cristian Newman on Unsplash

True female power knows how to live through the night alone, how to wander in the desert, how to go underground and live in a cave among the roots of life when necessary. She survives the conflagration, the invasion, the prison sentence, the betrayal, the loss, the beating, the chaos, the flood. A woman in her authentic power is rooted in the stars, in the trees, in the mountains, in the sea and in the earth. She welcomes cycles and seasons. Change is her strength. She knows how to bide her time and let die what must, because she knows her power will endure in women who come after her.

A woman in her power is not confused. She knows there’s no authentic power in money or position, youth or beauty or hairless legs. She knows her wellspring of power is internal and if she can’t find it, no one will. True feminine power defines her own success, her own goals, her own agenda, her own spiritual practice, her own beauty and her own rules.

Baba Yaga’s specialty is too-good maidens of all ages. That’s how I met her. When the Baba is finished with such a maiden, she’s either saltier and wiser or dead. Baba Yaga eats the dead ones with vinegar to cut the sweetness.

It’s a good time for prayers. Perhaps it’s always a good time for prayers. Here’s mine:

Baba Yaga, Grandmother, we offer you our sweat, tears, blood, milk and urine. Initiate us into life and death with our own blood and bone. Lead us back into love for ourselves, our bodies and our earth. Help us, your daughters, find our authentic feminine power again.

All content on this site ©2017

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted