by Jenny Rose | Dec 13, 2018 | Emotional Intelligence

My partner and I have been watching Lie To Me, a television series that ran on Fox from 2009 to 2011. The show is based on the work of Dr. Paul Ekman, the world’s greatest expert on facial expression.

Photo by Milada Vigerova on Unsplash

I am absolutely fascinated.

All my life I’ve been extremely aware of body language and what I’ve always called the “energy” of the people around me. I’ve frequently had the experience of picking up the hidden emotions of others and taking on responsibility for them, a result of ineffective boundaries. When I was trained in emotional intelligence I cleaned up my poor boundaries and many other destructive habits. I also began to openly and unapologetically trust myself after a lifetime of cognitive dissonance caused by the difference between words and nonverbal cues from others.

Now, at last, I have real world validation for the way I can sometimes “read” others. It’s not magic, and I’m not a freak, a fantasist or crazy. Science now recognizes the universality of human facial expressions for basic emotions (fear, surprise, contempt, happiness, sadness, disgust, shame), and technology allows us to slow down video footage and capture microexpressions, which occur in much less than a second, as we speak and interact with others.

Our words can lie, but Dr. Ekman’s work reveals our bodies give away our emotional experience in all kinds of ways of which we’re not even conscious. The way we hold our hands, a slight shoulder shrug, the way we move our heads, how we direct our gaze and small, fleeting expressions passing across our faces with the help of 42 complex muscles can contradict our words.

Photo by Joshua Earle on Unsplash

We know some people have a great deal of difficulty reading and interpreting body language and subtle cues, while others are skilled at it. Paul Ekman’s work and research makes it possible for anyone to consciously learn how to detect emotional deception. Every episode of Lie To Me incorporates not only a story line told by actors, but also footage from real people — politicians, leaders and other famous and infamous folks — displaying exactly the same facial expression or body movement. It’s amazing.

Some people are difficult to read. I’ve worked hard to develop a stone face and have often been told I’m opaque. My oldest son is extremely provocative, and my expressionless countenance stood me in good stead when he was a teenager and woke me in the middle of the night to tell me he was going to ski naked at midnight with a girl in one hand and a bottle of whiskey in the other. Any show of outrage or upset only egged him on, so I learned to control myself. I’ve also had some exposure to narcissists and other Cluster B people, who feed on emotional energy, and I know the best way to deal with them is to become a grey rock, that is to be so completely flat, uninteresting and uninterested that they move on, a technique far more effective than trying to get rid of them directly. Yet even though I may be harder to read than average, I know my body language gives me away every time, or would to a trained observer.

(Fortunately, my teenage sons were not trained observers. Let us be thankful for small mercies.)

Photo by Gary Bendig on Unsplash

Sedating substances and Botox injections can interfere with or blunt muscle movement and smooth out microexpressions, but eventually we all give our truth and lies away. We can’t help it. Microexpressions and body language are often totally unconscious on our part.

I’ve been told I have an intense gaze that can make others feel uncomfortable. I suspect this is a function of the focus and presence necessary to evaluate how the people around me present themselves as I compare what they say with what their expressions and bodies tell me. If I feel confused or receive a mixed message, I always go with body language. Words lie too easily and too frequently. We lie to ourselves and we lie to each other. When I experience cognitive dissonance as I observe and interact with others, now I no longer tell myself I’m making things up. Even more importantly, I don’t allow other people to make me feel bad and wrong. Nobody likes to have their cover blown, and someone with things to hide is naturally not going to appreciate feeling exposed. Rage, denial, projection, gaslighting and other abusive behavior can all be effective distractions from the truth.

A lie comes with a cost. The truth may come with a cost as well. We navigate our lives between the two, making the best choices we can. I have no desire whatsoever to uncover the secrets and lies of others, but I am interested in being able to evaluate if there are secrets and lies. I don’t believe we owe others 100% of our emotional truth, but every healthy relationship and connection requires some level of trust, and I don’t want to be with people I can’t trust. I think of mixed messages as a red flag.

It’s amazing to learn, after all these years of mysteriously and often uncomfortably picking up more information from others than I ever wanted to know, that inconsistency is a red flag. Words that are incongruent with facial expressions and body language are untrustworthy. My ability to recognize concealed emotions is not hateful or crazy.

Photo by Cristian Newman on Unsplash

Frequently we don’t seek to deceive others as much as we wish to deceive ourselves. The lies we tell ourselves are perhaps the most powerful of all, and we protect those kind of lies the most ferociously.

It’s important to understand recognizing the presence of a lie does not mean we know the substance of the lie or why it’s being told. As a writer, I find that why infinitely interesting in its possibilities. What kinds of things do we conceal? What motivates us to do so? What are the consequences of our various lies, great and small, to ourselves and to others? How do our bodies unconsciously communicate our emotional deception? If we spot emotional deception in someone we’re close to, what do we do with that information? What kinds of lies are terminal in relationships, and what kinds survivable? How do we forgive ourselves and others for emotional deception?

The looming presence of social media in our culture means many of our daily interactions, perhaps most, are not face to face, which greatly diminishes the complexity and depth of human communication and makes emotional deception easy. Body language is invisible. Tone, pitch and other verbal clues and idiosyncrasies are unheard. We use sanitized little emojis to represent our meaning, or at least to represent what we want others to believe our meaning is.

Paul Ekman has written several books I’m looking forward to exploring, and one can take online classes and learn more. I intend to learn a lot more.

Photo by Joshua Fuller on Unsplash

All content on this site ©2018

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted

by Jenny Rose | Oct 18, 2018 | Connection & Community, Emotional Intelligence, Shadows

I first heard about toxic mimics as I learned emotional intelligence. The term comes from radical environmentalist author and speaker Derrick Jensen. A toxic mimic is a destructive action, behavior or thing pretending to fill a primary human need. Rape is a toxic mimic for healthy, consensual sex. Sugar is a toxic mimic for food. Addiction is a toxic mimic for managing feelings. A job might be a toxic mimic for contribution. Pseudo self is a toxic mimic for authenticity. Some would argue that social media is a toxic mimic for connection.

I first heard about toxic mimics as I learned emotional intelligence. The term comes from radical environmentalist author and speaker Derrick Jensen. A toxic mimic is a destructive action, behavior or thing pretending to fill a primary human need. Rape is a toxic mimic for healthy, consensual sex. Sugar is a toxic mimic for food. Addiction is a toxic mimic for managing feelings. A job might be a toxic mimic for contribution. Pseudo self is a toxic mimic for authenticity. Some would argue that social media is a toxic mimic for connection.

I believe our modern culture here in the United States, at this moment, rests on an edifice of toxic mimics. People who create, design and sell toxic mimics have a simple agenda: Profit and power. We, the consumers and choice makers, the common people, if you will, happily hand over our power in exchange for the shiny; the new and improved; the seductive promise of success, wealth and love; and the popular. Toxic mimics give us the relief of distraction, instant gratification and the promise of an identity. They help us regulate our mood and feelings.

Toxic mimics have such power over us now that a majority of us (maybe) have voluntarily given management of our country to toxic mimics for human beings.

Photo by Patrick Brinksma on Unsplash

What are the strongest human motivators? Fear? Love? Hate? I could also make a case for denial, but that might be too inextricably bound up with fear to separate. Toxic mimics are deliberately designed and marketed to appeal to the things that drive us at our deepest levels. They are engineered to target our greatest vulnerabilities. They seek to hook us, permanently, helplessly and hopelessly, and they’re so powerful they kill many, many people. Witness the power of nicotine, for example. Toxic mimics promise to fill our lives with everything we want and provide us an identity, but when we employ them we feel emptier than ever. Because we are conditioned to believe buying a product or service will make us feel better, we buy as much as we can as fast as we can, which necessitates a continuous stream of money, a resource that has become one of the most powerful Gods we’ve ever worshipped. Money, one might say, is a toxic mimic for God, or Gods, or whatever word you like to use to communicate the divine.

The deepest irony in this situation is we are the ones who perpetuate the power of toxic mimics. We willfully and intentionally participate. We create demand and gobble up supply. We continue to support advertising, algorithms and the handful of powerful companies who monitor our lives and mine us for information in order to sell us yet more toxic mimics. We applaud and admire what we call “progress”, “growth” and a “healthy economy.”

Photo by Ev on Unsplash

A healthy economy. Healthy for who, I wonder. Healthy for the global system? Healthy for those of us living paycheck to paycheck? Healthy for the children who are victims (yes, I mean victims) of anti-vaxxers? Healthy for people who have no financial resource and thus cannot participate in the latest technology? In a country filled with disbonded children and broken families; rising antibiotic-resistant organisms, including STDs; rising illnesses like typhus which are perfectly preventable with vaccination; astronomical housing costs forcing employed professionals to live out of their cars; broken healthcare and public education systems and a population of obese, metabolically disordered, pharma-dependent, addicted, lonely, suicidal people, we have a so-called healthy economy.

Oh, good. I’m so proud to be an American.

It’s a lie. There’s nothing healthy about what’s happening now, but we’re so stupefied, so numbed, so habituated, that we no longer recognize lies when we hear them. We can’t afford to, because to recognize one means to recognize others, and if the whole thing is based on lies, we’re too afraid to know it. Much easier to cash the insurance check and rebuild, for the third or fourth time, in the same place than take responsibility for facing the effects, long predicted, of climate change.

Of course, insurance companies are not going to continue to subsidize climate change because it destroys their profits, so that might catch our attention — eventually.

In the meantime, we bend our heads over our handheld, shiny, talking, distracting and instantly gratifying techno-screens or settle down in front of our larger screens and surround sound systems and let the advertising and brainwashing wash over us. We call this life. Isn’t it grand? Isn’t it beautiful? Aren’t you happy?

In the meantime, we bend our heads over our handheld, shiny, talking, distracting and instantly gratifying techno-screens or settle down in front of our larger screens and surround sound systems and let the advertising and brainwashing wash over us. We call this life. Isn’t it grand? Isn’t it beautiful? Aren’t you happy?

A toxic mimic is a promise that never delivers. Sometimes we do it to ourselves. Sometimes we allow others to convince us of the necessity, morality and rightness of our toxic mimics. We’re told they will make us safe. They will make us successful. They will make us healthy and popular, beautiful and beloved. We’re told we have a perfect right to have what we want. We long to believe it. We buy, and then we don’t feel successful or beautiful, so we buy some more. We start giving away our power. We begin to hide our unhappiness. After all, toxic mimics are working for everybody else, aren’t they? Everyone on our favorite social media platform is doing just fine. We conclude there’s something wrong, broken and irredeemably ugly about us. It’s too shameful to admit or talk about. We take even more smiling selfies and post them.

Meanwhile, we elevate and empower not the humanitarians, the natural leaders, the ecologists, the visionary scientists, the emotionally intelligent, the critical thinkers and those who understand complexity and systems, but those who have wealth. Money, that amoral symbol made of paper and metal, is the God we’ve agreed is the most powerful and the most admirable. It’s not so, of course, but we make it so with our belief and our participation. We are driven by our fear of losing economically. We’re evidently prepared to follow the promise of economic power straight to Hell.

Fear is the most powerful hallmark of a toxic mimic. Fear of losing power. Fear of being wrong. Fear of consequences, justice and having to take responsibility. Fear of experiencing our feelings. Fear makes our lives, intellect and hearts smaller, not larger. Toxic mimics don’t meet our needs. They momentarily satisfy, perhaps, our cravings and addictions, our need for stimulation and gratification and our desire for distraction. Ultimately, however, toxic mimics dehumanize us, stop our critical thinking, retard our judgement, destroy our health, disable us from healthy connections and encourage us to hide our authenticity. Toxic mimics feed our rigidity, our ideology, our fear and paranoia, and actively attack our physical and mental health.

Are your needs being met? If you don’t know what your needs are, here’s a needs inventory to look at.

If that question made you cry, or your heart shouted “NO!”, make a list of all your makeup, your clothes, your car(s), your tech, your toys and the other stuff you recognize as part of your identity. Don’t forget your accounts, subscriptions and financial assets.

All that, and your needs are not being met?

Huh. Interesting, isn’t it?

All content on this site ©2018

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted

by Jenny Rose | Sep 13, 2018 | A Flourishing Woman, The Journey

Clarissa Pinkola Estes introduced me, years ago, to the idea of descansos in Women Who Run With the Wolves, one of the most important books I’ve ever read. Descansos is a Spanish word meaning resting places. A descanso might be a grave in an ordinary graveyard, but Estes suggests creating descansos as a spiritual practice; a method for letting go and/or acknowledging a loss; a place to put rage, fear and other feelings or destructive thoughts to rest so we don’t walk forward burdened by unresolved pain and experience.

We know grief has its own timetable. The Celts set aside a year and a day for the proper discharge of grief. Many other cultures have formal mourning periods and practices, during which people are not expected to fully participate in social responsibilities and activities. Many of us try to move away from the anguish of grief as quickly as possible, but there is no shortcut for the grieving process. Sooner or later, we must feel it and walk through it if we are to heal.

Photo by Madison Grooms on Unsplash

Loss is not just about the death of a loved one. As we journey through life we encounter many losses, including the loss of our innocence, which might take many forms; the loss of dreams; the loss of health; the loss of a job, a home, a relationship or some piece of identity. For all of these, we might make a descanso, a place where we have knelt and prayed, wept, planted flowers or a tree and marked with a cairn, a stone, a cross, or some other symbol that has meaning for us. A descanso is a quiet, private place apart from the rest of our lives, a place we can visit when autumn leaves begin to fall and the cooling air crisps with the scent of windfall apples, damp leaves and browning ferns. We pay homage to what has been, to that which we’ve blessed, released and laid to rest. We invite memory and take time to empty our cup of rage, pain or tears again.

I recently wrote about identity. This fall, it occurs to me to spread out all the pieces of my identity, past and present, try them on, one at a time, and notice how they feel. I will make descansos for those aspects of identity that no longer fit me or serve my intention going forward. I want an identity update; to replace the old versions with an identity compatible with my present life and experience, much like going through a clothes closet and culling.

In fact, that is a task I’m undertaking right now as well; going through my clothes. Perhaps that’s why I feel nostalgic and am thinking about descansos. Autumn awakens in me the desire to clean out and lighten up, literally and metaphorically. I discover my difficulty in letting go of clothing I haven’t worn in years and which no longer fits is about the memories of who I was and what I was doing while wearing it rather than the clothing itself.

Photo by eddie howell on Unsplash

Memories can be a heavy burden. Some are precious and we never want to lose them. Other memories haunt us and keep our wounds fresh and bleeding. The remedy for all those imprisoning beliefs, pieces of negative identity, unresolved feelings and painful memories is the practice of descansos, which is to say the practice of grieving and then moving on. That order is essential. We must grieve fully and willingly, and then move on. A graveyard is not a place to pitch a tent and live the rest of our lives. It’s a place to create, visit, honor, care for and meet ourselves when old parts and pieces of our lives enter our dreams and tug at our hearts.

Making descansos is a gentle practice. It is not denial, avoidance or rejection, but rather an open-armed welcome to all our experience, followed by honest assessment and choice-making. Like clothing, identity and memories wear out, no longer fit or become too uncomfortable and outdated to be useful. Making a resting place is an intentional practice, without violence, frenzy or horror. We are not tearing ourselves apart with self-hatred, but allowing change and growth, the same way the trees are beginning to let go of their leaves and a snake sheds its skin. The practice of descansos allows us to clean up, clean out, and create space for new growth and experience. It’s an opportunity to create a place of sacred memory so we do not have to stagger under a jumbled-up load of the past.

Creating descansos is uniquely individual. Some might draw a map of their life’s journey, marking descansos along the way. Artists might paint, make music, write, create, sculpt or dance. Others might seek out a sacred place in nature for ritual, prayer and making a grave or graves.

Photo by Sandy Millar on Unsplash

When I make descansos, I think of putting a baby to bed in a dim nursery, bathed and fed, sleepy and smelling of milk, with a clean blanket and a stuffed toy. Perhaps our most brutal memories and experiences are the ones needing the tenderest descansos we can create. As we would nurture, reassure and protect an infant, we nurture, reassure and protect ourselves with the practice of descansos. We allow ourselves to suffer, release our suffering and move on, honoring the way our experience shapes and enriches us.

It’s autumn in central Maine, a good time to make new descansos and visit old ones. A good time to remember. A good time to walk under the trees and absorb the wisdom of cycles and seasons, growth and change, life and death.

A good time to allow ourselves to rest in peace.

All content on this site ©2018

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted

by Jenny Rose | Aug 23, 2018 | Authenticity, Emotional Intelligence

Identity is everywhere. Identity theft, identity politics, job applications, and social media profiles confront us at every turn. We are constantly being commanded to prove our identity, not only formally, as in logging on to our bank accounts, but socially, in order to justify our existence, our beliefs and our values.

Technology has created new challenges in the way we talk about, understand and shape our identity. AI is no longer a piece of science fiction, and evidence grows regarding websites, social media trolls and other online entities that successfully manipulate, divide and interfere with social discourse, information and opinion.

We are woefully easy targets.

Photo by Roderico Y. Díaz on Unsplash

Merriam-Webster online defines identity as “sameness in all that constitutes the objective reality of a thing; the distinguishing character or personality of an individual.” The online Free Dictionary says identity is “the set of characteristics by which a person or thing is definitively recognizable or known; the awareness that an individual or group has of being a distinct, persisting entity.”

Objective reality. The term objective means “(of a person or their judgment) not influenced by personal feelings or opinions in considering and representing facts.” (Oxford Dictionary; emphasis mine.) This means a purple-polka-dotted snake cannot claim the identity of a green-striped zebra, no matter how indignantly and vociferously it insists it feels like one. Personality disorders are recognized as such because those who suffer from them are not always dealing with objective reality. A purple-polka-dotted snake who wants to be a green-striped zebra is divided tragically from itself and others, not only other purple-polka-dotted snakes, but all others, because it persists in trying to behave and be accepted as something it’s not, ultimately self-destructing.

Photo by Quino Al on Unsplash”

I’ve written before about labels, denial, arguing with what is and pseudo self, all of which ideas intersect with identity. Have you watched a potter at work with clay on a wheel? As they shape a vessel, one hand works inside and one outside. Identity is like that. The tribe we’re born into gives us our earliest sense of identity, and we take our cues from them. If our tribe is critical and we feel unaccepted and unloved, we internalize those voices and viewpoints and give them power in our psyche to mold our identity. At the same time, we go out into the world and our schools, jobs, communities, places of worship and other organizations identify us from the outside.

Years ago I worked with a group of gifted and talented middle and high school students as a school librarian. None of them fit in terribly well with their classmates. A young man I was very fond of was quite lonely, as well as being brilliant, and he said one day he was nothing but the “fat boy.” He was sixteen years old, and seemed resigned to carrying the identity of “fat boy” to the end of his life. I told him, entirely sincerely, that I never thought of him as the “fat boy.” He was obese. Obviously, I noticed. But to me he was a funny, interesting, curious, compassionate, vulnerable human being. His weight concerned me because of the social stigma and quality of his health, but I never thought of him as the “fat boy.”

He could see that I was telling him the truth. I haven’t any idea what happened to him or what he’s been doing all these years, but I’ve always hoped he remembered there was an adult in his life who saw beyond the limitations of “fat boy” and recognized other pieces of his identity and potential. I hope he learned at some point that he didn’t have to settle for a life defined by his weight.

Photo by Edu Lauton on Unsplash

Over the years of my lifetime, more and more people seem to never mature past teenage identity. We build websites, profiles and a social media presence, desperately trying to sell a successful identity for attention, true love, power or money. We are so compulsive about taking selfies that we die doing it. There’s an explosion of people seeking plastic surgery in order to match their digitally-altered pictures. We have the technology to alter hair color, eye color and physical characteristics, and we’re saturated with digitally-altered images on media that keep us firmly convinced we’re unattractive and imperfect as we are. At the same time, we socially reinforce and perpetuate ridiculous gender, racial and ethnic roles, limitations and expectations.

Perfect strangers insist on imposing labels on us, or try to bully us into choosing one label over another. It’s an either-or black-and-white world, and new labels proliferate like maggots in road kill, creating ever-increasing lines of division and arenas for conflict.

Photo by Chris Barbalis on Unsplash

We are in such a hurry, we’re so overstimulated and anxious to not be left behind and to be validated, we’ve forgotten the simplicity of identity, and we’ve forgotten we don’t owe the world a public explanation or justification of our identity. Having a Facebook or Tinder profile does not constitute an identity. Having feelings and opinions about who we are is not an identity. Our carefully constructed pseudo self is not an identity. Our identity is not maintained and created by what others think, feel or say about us. Identity is not an endpoint, but a journey. Healthy identity is flexible. It adapts and changes as we live our lives. We are not who we wish we were, who we are afraid we are or necessarily who we think we are. We are not exactly who we were yesterday or who we’ll be tomorrow. We’re certainly not necessarily what others tell us we are, or must be, although objective reality always trumps our internal fantasies.

Our identity, like our power, is ours alone. We need not sell it or give it away, and it cannot be stolen from us. On the other hand, we must take responsibility for our own self-sabotage and mental disorders if we seek a healthy identity.

Healthy identity is complex and multi-dimensional. I’ve been daughter, sister, wife and mother, and I’m much more than any of those single roles. I’ve worked several jobs over my lifetime, but I’m more than any of those jobs. I have a physical identity in terms of vital statistics, Caucasian skin, blue eyes and female biology, but none of those markers identify me as completely as the fact that I’m a human being. A healthy identity also accommodates shadows, scars, less-than-useful coping mechanisms and behavior patterns.

My wish simply is to live my life as fully as I can. In both our work and our leisure, I think, we should be so employed. And in our time this means that we must save ourselves from the products that we are asked to buy in order, ultimately, to replace ourselves.”

Wendell Berry, The Art of the Commonplace: The Agrarian Essays

Tech allows us to create superficial fantasies of bright colors and pleasurable images, but those worlds are empty and brittle, like an enticing piece of candy that melts in a minute on our tongue and leaves nothing but the taste of sugar and artificial flavor. We cannot judge identity by houses, gardens, cars, vacations, pets, children, selfies, clothing, jobs or partners. Our possessions, our pictures and our memorabilia are not our identity. Somewhere, under all that stuff, behind all those pictures of success and happiness, apart from our fear and unwillingness to come to terms with our objective reality and our denial, lies the powerful, complex, fascinating, valuable person we really are, and that person longs to be identified and welcomed into life. That person longs to give and receive love, make a valued contribution and live authentically.

I’m interested in the way people self-define and introduce themselves. It always points to either what we ourselves feel is the largest part of our identity or what we think others will value or connect with most readily. This is what lies beneath every dating profile. What do we imagine prospective partners will be most attracted to? What’s the perfect thing to say which will limit unwanted matches and encourage those we imagine might provide whatever we’re looking for? How can we optimize the algorithm and make it work for us?

Sometimes I walk away from meeting a new person feeling overwhelmed and deafened by all the ways they labeled themselves but with no sense of the real human being I just interacted with. Instead of an easy, exploratory, getting-to-know-one-another conversation, I was bludgeoned with political jargon and identifiers, patronized and gratuitously instructed out of some kind of claimed expertise. It feels aggressive, weak and demanding. This is who I am and you will recognize my status, authority and identity! If you don’t apply one of my proud labels to yourself, you should. All the best people do. In any event, my labels are better than yours.

Our identity is not for others, but for ourselves. We’re the ones who need to know who we are, experience our feelings and monitor our thoughts. We’re the ones in charge of our dignity, our sexuality and our choices. We’re the ones responsible for our own integrity. As my hair greys and my fertility wanes, I become more and more physically invisible in the world. At the same time, I’ve never been as strong, as resilient, as wise and as compassionate as I am now. I’ve never loved so well. I’ve never felt so whole or comfortable in my own skin. I have no social media accounts and no cell phone. I don’t use any kind of apps, dating or otherwise. My identity is strong and dynamic, and it’s not for sale or on display. In fact, I’ve always felt being invisible is a great advantage. People who attract no attention are invariably underestimated and overlooked, especially aging female people.

At the end of the day, a life well lived is about being who we are, objective reality included, because everyone else is taken. Fantasy is fun, but real life is where all the juice is.

My daily crime.

“I look like vanilla pudding so nobody knows that on the inside I am spider soup.”

Andrea Portes, Anatomy of a Misfit

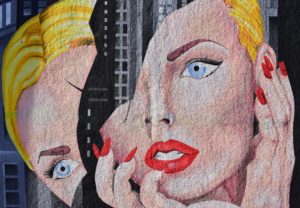

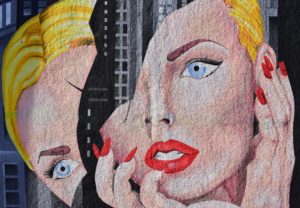

Photo by Cristian Newman on Unsplash

All content on this site ©2018

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted

by Jenny Rose | Jul 26, 2018 | Connection & Community, Emotional Intelligence, Shadows

I looked up the word “denial” to find a quick definition as a starting point for this post. Fifteen minutes later I was still reading long Wiki articles about denial and denialism. They’re both well worth reading. I realize now the subject of denial is much bigger than I first supposed, and one little blog post cannot do justice to its history and scope.

Photo by Ian Espinosa on Unsplash

I wanted to write about denial because I keep tripping over it. It seems to lurk in the background of every experience and interaction, and it’s nearly always accompanied by its best buddy, fear. I’ve lately made the observation to my partner that denial appears more powerful than love in our culture today.

I’ve written before about arguing with what is, survival and being wrong, all related to denial. I’ve also had bitter personal experience with workaholism and alcoholism, so denial is a familiar concept and I recognize it when I see it.

I see it more every day.

I was interested to be reminded that denial is a useful psychological defense mechanism. Almost everyone has had the experience of a sudden devastating psychological shock such as news of an unexpected death or catastrophic event. Our first reaction is to deny and reject what’s happening. Elisabeth Kubler-Ross identified denial as the first of five stages of psychology in a dying patient. Therein lies the distinction between denial as part of a useful and natural cycle and denial as a permanent coping mechanism. In modern psychology denial is followed by other stages as we struggle to come to terms with a difficult event. We (hopefully) move through the stages, gathering our resources to cope with what’s true and coming to terms with the subsequent changes in our lives.

Denialism, on the other hand, is a “choice to deny reality as a way to avoid a psychologically uncomfortable truth” (Wikipedia). For some, denial is an ideology.

In other words, denialsim is all about fear, fear of being wrong, fear of change, fear of painful feelings, fear of loss of power, fear of one’s cover being blown. This is why some of the most rabid and vicious homophobes are in fact homosexual. Unsurprisingly, projection and gaslighting are frequently used by those who practice denialism.

I’ve no doubt denial is an integral part of the human psyche. I never knew anyone who didn’t have a knee-jerk ability to deny. I do it. My partner does it. My friends and family do it. My partner and I have a code phrase: “I’m not a vampire,” that comes from the TV series Angel in a hilarious moment when a vampire is clearly outed by one of the other characters. He watches her put the evidence together: “… nice place… with no mirrors, and… lots of curtains… Hey! You’re a vampire!” “What?” he says. “No I’m not,” with absolutely no conviction whatsoever. It always makes us giggle. If Angel is too low-brow for you, consider William Shakespeare and “the lady doth protest too much, methinks.” Denial is not a new and unusual behavior.

Photo by NASA on Unsplash

The power of denial is ultimately false, however. Firstly and most obviously, denial does not affect the truth. We don’t have to admit it, but truth is truth, and it doesn’t care whether we accept it or not. Secondly, denial is a black hole of ever-increasing complications. Take, for example, flat-earthers. Think for a moment about how much they have to filter every day, how actively they have to guard against constant threats to their denialsim. Everything becomes a battlefield, any form of science-related news and programming; many types of print media; images, both digital and print, now more widely available than ever; and simple conversation. I can’t imagine trying to live like that, embattled and defensive on every front. It must take enormous energy. I frankly don’t understand why anyone would choose such hideous complications. It seems to me much easier to wrestle with the problem itself than deal with all the consequences of denying there is a problem.

Maybe that’s just me.

It seems our denial becomes more important than love for others or love for ourselves. It becomes more important than our integrity, our health, our friends and family, loyalty, and respect or tolerance. Our need to deny can swallow us whole, just as I’ve seen work and alcohol swallow people whole. Denial refuses collaboration, cooperation, honest communication, problem solving and, most of all, learning. Denialism is always hugely threatened by any attempt to share new information or ask questions.

Photo by Jonathan Simcoe on Unsplash

Denial is a kind of spiritual malnutrition. It makes us small. Our sense of humor and curiosity wither. Fear sucks greedily on our power. We become invested in keeping secrets and hiding things from ourselves as well as others. We allow chaos to form around us so we don’t have to see or hear anything that threatens our denial.

This is not the kind of fear that makes our heart race and our hands sweat. This is the kind of fear that feels like a slamming steel door. It’s cold. It’s certain. We say, “I will not believe that. I will not accept that.”

And we don’t. Not ever. No matter what.

A prominent pattern of folks in denial is that they work hard to pull other people into validating them. Denial works best in a club, the larger the better. The ideology of denialism demands strong social groups and communities that actively seek power to silence others or force them into agreement. Not tolerance, but agreement. This behavior speaks to me of a secret lack of strength and conviction, even impotence. If we are not confused about who we are and what we believe, there’s no need to recruit and coerce others to our particular ideology. If you believe the earth is flat, it’s fine with me. I’m not that interested, frankly. I disagree, but that’s neither here nor there, and I don’t need you to agree with my view. When I find myself recruiting others to my point of view, I know I’m distressed and unsure of my position and I’m not dealing effectively with my feelings.

I’ve written before about the OODA loop, which describes the decision cycle of observe, orient, decide and act. The ability to move quickly and effectively through the OODA loop is a survival skill. Denial is a cheat. It masquerades as a survival strategy, but in fact it disables the loop. It keeps us from adapting. It keeps us dangerously rigid rather than elegantly resilient.

Some people have a childlike belief that if something hasn’t happened, it won’t, as in this river has never flooded, or this town has never burned, or we’ve never seen a category 6 hurricane. Our belief that bad things can’t happen at all, or won’t happen again, pins us in front of the oncoming tsunami or the erupting volcano. It allows us to rebuild our homes in places where flood, fire and lava have already struck. We ignore, minimize or deny what’s happening to the planet and to ourselves. We don’t take action to save ourselves. We don’t observe and orient ourselves to change.

Some things are just too bad to be true. I get it, believe me. I’m often afraid, and I frequently walk through denial, but I’m damned if I’ll build a house there. The older I get, the more determined I am to embrace the truth. I don’t care how much pain it gives me or how much fear I feel. I want to know, to understand, to see things clearly, and then make the best choices I can. It’s the only way to stay in my power. I refuse to cower before life as it is, in all its mystery, pain and terrible beauty.

Ultimately, denial is weak. I am stronger than that.

Photo by Joshua Fuller on Unsplash

All content on this site ©2018

Jennifer Rose

except where otherwise noted