by Jenny Rose | Dec 3, 2022 | Aging, Connection & Community, Emotional Intelligence

I once saw the movie 50 First Dates, about a young woman who had no memory. Every day she woke up as a clean slate with no past.

The movie gave me the heebie-jeebies. I’ll never watch it again. In several close relationships, both family and romantic, I’ve experienced the devastating grenade of “I forgot,” or “I don’t remember that.”

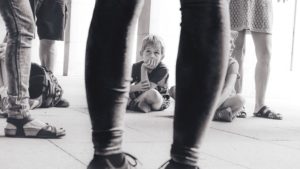

Photo by John Salvino on Unsplash

In chronically abusive and dysfunctional family systems, “I don’t remember that” effectively shuts down any way forward into mutual responsibility, understanding or healing. Our traumatic memories suddenly waver. Did we, after all, make it all up? Did we misunderstand for years and decades? Are we unforgiving, mean and petty of spirit, hateful? Most frightening of all, are we crazy? If we’ve been chronically gaslit, we certainly feel crazy.

In “romantic” relationships, this memory failure is equally damaging. It blocks conflict resolution and discussion. If it’s true, it means the forgetful partner is unable to learn and adapt to the needs of the relationship and the other partner. There can be no learning and growing together. Nothing can change.

Most of all, this kind of response feels to me like an abdication, code for “it’s not my fault and I refuse to take responsibility.” It’s a signal I’m on my own with my questions and my need to understand.

It’s like a door slammed in my face, and I don’t beat on doors slammed in my face, begging for entry. I walk away.

Now I have a relative with dementia, and it’s extraordinary. I have never felt able to get close to this person before, though I have loved them deeply all my life. I’ve also never felt I was anything but a disappointment and a burden to them. I couldn’t find a way to get past their lifetime of accumulated trauma and pain, bitterness and rewritten narratives. As a truth seeker, I’ve been continually stymied and suspicious, believing I could not trust them to ever tell me the plain truth about anything.

Most painful of all, the fullness of my love has been rejected, over and over, for decades. Nothing I am or have to give was welcome; most of it was distinctly unwelcome.

Now I am witnessing a kind of metamorphosis. Gradually, gently, like leaves falling from trees in autumn, my loved one is letting go of their memories. And in some elemental way, as I walk beside them (because I have always been beside them), I am releasing the pain of my memories.

My loved one has experienced periods of extreme agitation and distress, and those are terrible for everyone. But, as the days pass, those periods seem to have passed too, and now I’m witnessing a gentle vagueness, a dream-like drifting, and in some entirely unexpected and inexplicable way I feel I’m at last catching a glimpse of the real person I’ve always wanted to know.

Even more amazing, I can now say “I love you very much,” that simple truth I’ve never been able to freely express, and they say it back to me. And I believe them.

After all these decades of pain and suffering, separation and bleeding wounds, I am finally able, in the words of Eden Ahbez, “just to love and be loved in return.”

This was all I ever wanted out of this relationship (and most others). Just this. To love fully and be loved in return. And I don’t care if it’s only in the moment. I don’t care that they’ll forget this elemental exchange of words of love as soon as they hang up the phone, or possibly before that.

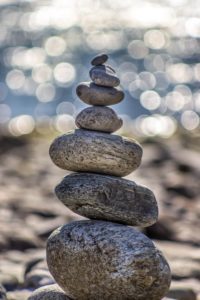

What matters to me is they hear me, they accept my love, they return it. I’ve never had that with this person before. Maintaining bitterness, rewriting history, remembering old hurts, all require memory. And their memory is loosening, unraveling. What’s left is a person I’ve always sensed was there, a person of innocent simplicity, an undamaged personality who can participate in love. Someone who is not haunted by their past. Someone, oddly, who I trust.

Photo by James Pond on Unsplash

Whatever the next interaction brings, I don’t have to go into it fully armored. Forgiveness has no meaning when dealing with dementia. Cognitive decline is unpredictable, clearly out of anyone’s control. Whatever is said in any given moment will not be remembered, whether words exchanged are of love or not. So, there’s no point in me remembering, or taking anything personally, or trying hard to be acceptable, do it right, stay safe. It feels safe to trust again, to trust the naked soul I’m dealing with now. I don’t have to try to repair our relationship. My feelings of duty and obligation are meaningless, because those expectations reside in memory, and memory flutters in the winter wind, frayed and thin.

My loved one has attained, at least periodically, a kind of peace they have never demonstrated before in my lifetime. Peace from the past. Peace from emotional pain. Because they are at peace, I, at last, can also be at peace.

I hoped death would free us both. I never expected dementia would do it first. We have both found absolution, at least for now.

Whatever comes, these interactions are precious to me. I realize now I still reside somewhere in the heart of this damaged, unhappy person. I was and am loved, at least as best they could and can. Knowing that, feeling it at last, changes everything and heals much.

I am beyond grateful. And that’s a strange feeling in this context. Dementia takes so much away … In this case, it’s loosened prison bars and chains, unlocked shackles and manacles, and left behind something pure and tender, a glimpse of someone fresh and unscarred in an aged and battered body.

I wonder how much of our identity is built from our social context memories. Too bad we can’t just delete certain files, wipe our hard drive clean in spots, and begin again.

I ask myself if it’s wrong to be so happy, so grateful, so relieved at this unexpected turn of events. I tell myself I should feel guilty. I’ve occasionally worked with Alzheimer’s patients, and I frequently work with people who are dealing with dementia and Alzheimer’s in their loved ones. I’ve never heard anyone suggest anything positive about it. Once again, I seem to be totally out of step.

I don’t take my self-doubt terribly seriously, though. I always think I’m doing life wrong. I’ve learned to tell that voice to shut up and sit down. Wrong or right, I feel a kind of exhausted joy at the lessening, maybe even the cessation of my loved one’s emotional suffering. Since I was a child I’ve wanted their health and happiness, their peace, wanted it more even than to be allowed to love and to be loved. I never expected those first passionate prayers from my child self would be answered, let alone in this manner. But here we are.

I try

to remember

my former life

and realize how quickly

the current travels

towards home

how those

dark and irretrievable

blossoms of sound

I made in that time

have traveled

far-away

on the black surface

of memory

as if they no longer

belonged

to me.

From “The Sound of the Wild” by David Whyte

To read my fiction, serially published free every week, go here:

by Jenny Rose | Nov 19, 2022 | A Flourishing Woman, The Journey

I was taught, as a child, it was my job to alleviate distress. One must always respond immediately and help the sufferer. It went far beyond duty and obligation. If I did not fix the distress of others, my childish world would fall apart. Everyone would leave.

Photo by Cristian Newman on Unsplash

For a child, such consequences are death.

I was also taught “help” meant doing anything and everything I was asked to do, immediately, unquestioningly, and unendingly. My own distress was of no consequence at best and a direct threat, an unwelcome competition, at worst.

That core teaching stayed with me as I grew up, and has been a keynote of my behavior and experience most of my life. I wanted to help people. When people around me suffered, I felt an overwhelming, painful panic, as well as complete responsibility. I had to do everything I could, give the situation my all in order to “help.”

I also grew up with an inability to respond to my own distress. Hunger, thirst, fatigue, emotional and physical pain, were all ignored. My disconnection from my own needs and experience led me into chronic pain, eating disorder, depression, and anxiety. I was unaware of my traumatic wounds. I had no interest in helping myself. Helping myself was selfish, bad, and unloving.

Then I studied emotional intelligence and all the work and therapy I’d done over the years with guides and teachers as well as on my own (see my Resources page) wove together into an intention to reclaim my health and my self.

This blog has been a key part of that work.

I still don’t like to watch people suffer, but I’m more careful now about “helping.” I’ve learned suffering is not necessarily the enemy. We get ill, have painful emotional and physical injuries, have uncomfortable feelings. We age and our bodies and sometimes our minds wear out. To be human is to experience these things; they’re inescapable. We can’t control what happens to us, but we can control how we deal with such events. When someone is suffering, I’ve learned to be less reactive, to remember it’s not my fault or my responsibility to fix it. I’ve learned to notice whether the sufferer is helping themselves before I jump in.

Photo by Joshua Earle on Unsplash

I have learned a bitter lesson: No one can help someone who will not help themselves.

I realize now we can’t always go back to where we were before we were wounded; we can’t always heal the wound itself. Sometimes our wounds and suffering are taking us into something new and what’s called for is not healing, but tolerance and patience.

What does “help” mean? This is an important question. Does help mean we respond promptly to all demands, whether or not they are safe, sustainable, or even possible? Does help mean we make thoughtful, intentional choices for safety and practicality even if those choices go against what we are being asked to do in terms of “help?” Do we decide what the best “help” is, or does the sufferer get to choose what kind of “help” they want?

I’m still uncomfortable talking about my own pain. Honestly, I’m still uncomfortable even noticing it, but I practice every day at staying present with how things are with me. It feels selfish and wrong, but I know that feeling doesn’t mean it is selfish and wrong, just that it’s very different from my early training. Sometimes the choice that feels worst is the best choice. Sometimes suffering is the only possible road forward into peace, growth and resilience.

None of us has the power to help anyone avoid suffering. I confess I’ve argued with that reality all my life, but it hasn’t done a bit of good. In fact, it’s done harm, most of all to myself.

I have occasionally, in the depths of anguish, asked for help. When I do that, what am I asking for?

Nothing tangible. Not money or a thing. Not love. Not sex. Not a gallon of ice cream. I’m not asking for someone to come along and fix it all, or take responsibility.

I’m asking to be heard. I’m asking for someone to say, “I’m here. You’re not alone. I believe in you. I know your goodness, your strength, your courage.” I’m asking for a safe place to discharge my feelings. This might involve snot, wet Kleenexes, rage, and a raised voice.

A safe place is not a place where someone else takes responsibility and fixes, or asks me to stop feeling my feelings, or is clearly uncomfortable with my suffering. A safe place is provided by someone with healthy boundaries who is willing to witness my distress without feeling compelled to fix it.

Witness. A witness. That’s ultimately what I want. Just someone to be there with me for a little while. I can face my own demons and challenges, but I can’t do it all alone.

Photo by Gemma Chua Tran on Unsplash

None of us can. We are social animals. But we can witness for one another. We can sit quietly, holding a safe space without judgment or a fix or advice, and just witness. Pass the Kleenex.

It’s the hardest thing in the world for me to do. Simply witnessing seems so passive, so weak, so useless. Someone right in front of me is deeply distressed and I simply sit like a bump on a log witnessing? Are you kidding me?

Surely, I can do better than that. I can do more than that. It’s up to me to make their suffering stop!

And yet. And yet. Isn’t finding a witness incredibly hard? How many people in our lives can take on such a role? What an inestimable gift, to be willing to walk beside someone who is suffering, to be willing to stay, to not look away. What if our boundaries were so healthy we could do that? What if we weren’t afraid of suffering? What if we were wise enough, strong enough, to make room for it and sit down beside it?

Someone I love is in great anguish of spirit. They beg me for help, but a very specific kind of help which is ethically and practically impossible for me or anyone else to give. Which makes me an enemy. Which makes my loved one even more alone than they already feel, more victimized, more powerless, more confused.

There is nothing about this that doesn’t suck. I dread the phone calls beyond words because I don’t want to witness this suffering. It feels unbearable. But my loved one must bear it, and if they have to, I can. I choose to witness. It feels like nothing. It’s not what’s wanted. But at this point it’s all I can do. So I will keep calling and answering calls. I will get up in the morning and talk to case managers, nurses, CNAs, palliative care consultants, nursing homes, and whoever else will talk to me. I will update friends and family. Then I will get up the next morning and do it again.

I pray there is some power in witnessing, some rightness. I pray that somehow my love and willingness to remain a witness does a little bit of good, provides some small comfort, lights a candle in the darkness of dementia, even for a moment.

And I search inside my own suffering for wisdom, for healing, for grace, and for faith.

To read my fiction, serially published free every week, go here:

by Jenny Rose | Sep 11, 2022 | Choice, Power

Probably every child is told we all have to do things we don’t want to do.

Photo by Cristina Gottardi on Unsplash

Children are concrete, and I was no exception. When I heard we all have to do things we don’t want to do, I thought it meant that’s what life was supposed to be about, a kind of slavery to all those things we don’t want to do. No one talked to me about balance, or doing the things we do want to do.

It made life seem like an unhappy business, years and years of unending duty, responsibility, and doing what I didn’t want to do. No recess. Or maybe what I really wanted to do was bad and wrong? Maybe I should want to do what I didn’t want to do. I wasn’t sure. A part of me went underground. I didn’t want anyone to know how bad I was, how flawed. I worked hard at the things I didn’t want to do and hid the things I did want to do, in case they were wrong.

But I couldn’t conceal the feeling of wanting and not wanting from myself. I used to make hidey holes in whatever house we were living in at the time and go to ground with a book, but I always felt guilty. I wanted to read. Doing what I wanted to do was bad. I should have been helping my mom do all the things she didn’t want to do.

The pronouncement that we all have to do things we don’t want to do is stated as a Cosmic Truth, especially as an adult tells it to a child. It’s loaded with feelings and experience a child can’t possibly understand, but the subtext was clear to me:

Life is not much fun.

I can’t resist picking apart Cosmic Truths as an adult, and as I think about this one it occurs to me it really has to do with personal power more than wanting or not wanting. It’s not framed in terms of personal power because our emotional intelligence is so low. Making choices based on whether we want to do something or not is childish. Power resides in the act of choice, not in the wanting or not wanting.

Steering our lives solely by our desires is hedonism, a belief that satisfaction of desires is the purpose of life. Desire, though, is so shallow, so fleeting. And it’s never permanently satisfied. No matter how well and pleasurably we’ve eaten, we’ll be hungry again. Desire is a treadmill we can never get off.

This is not to say we shouldn’t ever choose something we want or say no to something we don’t want, but our desire is easily manipulated. That’s why advertising works. If we can be easily manipulated, we’re not standing in our power. Addiction is based, at least in the beginning, on wanting and not wanting.

A more useful question than What do I want to do? is What would be the most powerful thing to do? We might want to eat a carton of ice cream, but a walk feeds our health, well-being, and thus personal power much better. After all, one carton of ice cream leads nowhere but to another. Personal power can lead us to joy and experience a carton of ice cream never dreamed of.

- If we don’t choose to do difficult, frightening, or new things, we’ll never grow.

- If we don’t choose to take care of our bodies, they won’t function well.

- If we don’t choose to be self-sufficient and resilient, we’ll be dependent.

- If we don’t choose to learn anything, we’ll remain ignorant.

- If we don’t choose to plan ahead, prepare, or manage consequences, we diminish our choices, waste resource, and weaken the contribution we’re capable of making.

- If we don’t choose the responsibility of commitment and making choices, someone else will make our choices for us.

And so on.

I’m changing the frame. I’m less interested in what I want and what I don’t want and more interested in how my choices affect my power, and the power of those around me. I’m willing to do what I don’t want to do if it’s a step on a road leading to integrity, power, healthy relationship, or anything else important to me. At the same time, I can exercise my right to say no to things that won’t take me where I want to go.

It’s about power, not desire. Any three-year-old can want and not want. It takes an adult to manage a healthy balance of personal power.

Photo by Deniz Altindas on Unsplash

by Jenny Rose | Aug 27, 2022 | Connection & Community, Emotional Intelligence

A little over three years ago I wrote a post titled “Questions Before Engagement.”

Since then, the world has changed, and so have I.

I’m not on social media, but my biggest writing cheerleader is, and he tells me people are talking about how to recognize red flags. He suggested I post again about problematic behavior patterns.

A red flag is a warning sign indicating we need to pay attention. It doesn’t necessarily mean all is lost, or we’ve made a terrible mistake, or it’s time to run. It might be whoever we’re dealing with is simply having a bad day. Nobody’s perfect.

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

A persistent pattern of red flags is significant. Ignoring problematic behavior sets us up to get hurt.

The problem with managing red flags is we may be flying several ourselves, and until we figure out our own behavior we’re going to struggle to deal effectively with others.

We all have an excellent built-in system alerting us to possible danger. We call it intuition, going with our gut, or having a hunch or a feeling. We may not know why we feel uneasy, but we subconsciously pick up on threatening or “off” behavior from others. The difficulty is we’re frequently actively taught to disregard our gut feelings, especially as women. We’re being dramatic, or hysterical, or a bitch. We’re drawing attention to ourselves, or making a scene. What we saw, heard or felt wasn’t real. It didn’t happen, or if it did happen, we brought it on ourselves.

We live in a culture that’s increasingly invalidating. Having a bad feeling about someone is framed as being hateful, engaging in profiling, or being exclusive rather than inclusive. Social pressure makes it hard to speak up when we feel uncomfortable. Many of the most influential among us believe their money and power place them above the law, and this appears to be true in some cases. In the absence of justice, we become apathetic. What’s the point of responding to our intuition and trying to keep our connections clean and healthy when we can’t get any support in doing so?

If we grow up being told we can’t trust our own feelings and perceptions, we’re dangerously handicapped; we don’t respond to our intuition because we don’t trust it. We talk ourselves out of self-defense. We recognize red flags on some level, but we don’t trust ourselves enough to respond appropriately. Indeed, some of us have been severely punished for responding appropriately, so we’ve learned to normalize and accept inappropriate behavior.

So before we concern ourselves with others’ behavior, we need to do some self-assessment:

- Do we trust ourselves?

- Do we respond to our intuition?

- Do we choose to defend ourselves?

- Do we have healthy personal boundaries?

- Do we keep our word to ourselves?

- Do we know how to say both yes and no?

- Do we know what our needs are?

- Are we willing to look at our situation and relationships clearly and honestly, no matter how unwelcome the truth might be?

Photo by freestocks.org on Unsplash

Once we’ve become familiar with our own motivation and behavior patterns, we can turn our attention outward and focus on the behavior of those we interact with.

Red flags frequently seem too bad to be true. In intimate relationships with partners and family, the anguish of acknowledging toxic or dangerous behavior and setting limits around it cannot be overstated. Those we are closest to trigger our deepest and most volatile passions. This is why it’s so important to be honest with ourselves.

The widest lens through which to examine any given relationship is that of power-over or power-with. I say ‘lens’ because we must look and see, not listen for what we want to hear. Talk is cheap. People lie. Observation over time tells us more than words ever could. In the case of a stranger offering unwanted help with groceries, we don’t have an opportunity to observe over time, but we can say a clear “no” and immediately notice if our no is respected or ignored. We may have no more than a minute or two to decide to take evasive or defensive action.

If we are not in an emergency situation, or dealing with a family member or person we’ve known for a long time, it might be easier to discern if they’re generally working for power-with or power-over. However, many folks are quite adept at using the right words and hiding their true agenda. Their actions over time will invariably clarify the truth.

Power-over versus power-with is a simple way to examine behavior. No labels and jargon involved. No politics. No concern with age, race, ethnicity, biological sex, or gender expression. Each position of power is identifiable by a cluster of behaviors along a continuum. We decide how far we are willing to slide in one direction or another.

Power-Over

- Silencing, deplatforming, threatening, personal attacks, forced teaming, bullying, controlling

- Win and be right at all costs

- Gaslighting, projection, DARVO tactics (Deny, Attack, Reverse Victim and Offender)

- Fostering confusion, distrust, disinformation, and violence

- Dishonesty

- Poor communication and refusing to answer questions

- Emotional unavailability

- High-conflict behavior

- Blaming and shaming of others

- Refusal to respect boundaries

- Inconsistent

- Refusal to discuss, debate, learn new information, take no for an answer

- Lack of reciprocity

- Lack of interest in the needs and experiences of others

Power-With

- Encouraging questions, feedback, open discussion, new information, ongoing learning, critical thinking

- Prioritizing connection, collaboration, and cooperation over winning and being right; tolerance

- Clear, consistent, honest communication

- Fostering clarity, trust, information (facts), healthy boundaries, reciprocity, authenticity, and peaceful problem solving

- Emotionally available and intelligent

- Taking responsibility for choices and consequences

- Words and actions are consistent over time

- Respect and empathy for others

We don’t need to be in the dark about red flags. Here are some highly recommended resources:

- The Gift of Fear by Gavin de Becker

- Bill Eddy’s website and books about high-conflict personalities

- Controlling People by Patricia Evans

Image by Bob Dmyt from Pixabay

by Jenny Rose | Aug 20, 2022 | Connection & Community, Emotional Intelligence

Trust: Firm belief in the reliability, truth, ability or strength of someone or something (Oxford Online Dictionary)

Mistrust: General sense of unease towards someone or something

Distrust: Specific lack of trust based on experience or reliable information

Leo Babauta recently published a piece on practicing trust which has given me much food for thought.

Trust is an uncomfortable subject for me. For most of my life I’ve considered myself to be shamefully distrustful. As I’ve learned emotional intelligence, I’ve realized I have plenty of good reasons for my mistrust and distrust, but there’s still a part of me that feels I should be more trusting, more willing to give others a second, or third, or hundredth chance, less guarded, more open, more forgiving.

Photo by Liane Metzler on Unsplash

Except I know intellectually forgiveness does not mean an automatic reinstatement of trust.

In my heart, I feel like a bad person, especially a bad woman, because throughout my life people who say they love me have appeared to be hurt by my lack of trust. Yet those same people have given me reasons not to trust them.

When I wind up in these confusing emotional cul-de-sacs, I blame myself. I’m being too dramatic (again). I’m being a bitch. I’m mean. I can’t love, or let anyone love me. (Does trust = love? Does all love automatically come with trust?) When I explain the specific events leading to my mis- or distrust, I’ve frequently been told the other party doesn’t remember saying what they said or doing what they did. This implies I’m nitpicking, ridiculously sensitive, keeping score, or even making it up. I wonder if I’m being gaslighted, or if I’m just not a nice person.

Years and years ago I made a rule for myself: give every situation or person three chances before deciding not to trust. It still feels fair to me. Sometimes things happen. We have a bad day. We say hurtful things, or don’t keep our word, or make a boneheaded choice, breaking trust with someone. I know I’ve done it, and I’d like to be given the benefit of a doubt.

The benefit of a doubt is fair, right?

I still follow that rule. It feels appropriately kind to others and like good self-care. Yet I feel guilt nearly every day over the people in my life who I want to trust, feel that I should trust, and don’t trust.

Babauta’s article specifically addresses signs of distrust of ourselves, and some ideas about practicing self-trust. I never connected problems with focus, fear or uncertainty, procrastination or indecision with lack of self-trust, but I can see they might be. If we don’t trust our priorities, resilience, or choices, it’s difficult to be decisive or take risks with commitments and problem solving.

If we don’t trust ourselves to cope effectively with sudden changes and reversals and frightening situations, uncertainty and chaos disable us, making us vulnerable to anyone or anything promising relief, certainty, or help.

The boundary between trust in ourselves and trust in others is permeable. If we define ourselves, as I do, as “having trust issues,” presumably that includes issues with ourselves as well as others.

It makes me shudder to imagine living with no feeling of belief in the reliability, truth, ability or strength of anyone or anything. How could anyone sustain such an emotionally isolated condition, not only from those around them but from themselves?

I do have people in my life I trust. Is it possible I don’t have trust issues? Is that just a polite, apologetic, and roundabout way of avoiding a direct “I don’t trust you?”

Do I have to answer that?

It’s true I trust far fewer people than I distrust.

But it’s also true I give people and situations a chance. Three chances, in fact. At least.

Why does it seem so cruel to tell someone we don’t trust them?

Trust, as I experience it, is not all or nothing. I might trust a person to be kind and caring but never allow them to drive me anywhere. I might trust a person with money but never trust them to be on time. I trust myself to be there for others, but I haven’t trusted myself to be there for me.

Consumerism is about distrust. We’re actively groomed to distrust ourselves. Yesterday I was laughing with a friend about articles on MSN. There was an article about trends and fashion in decorating, as though it matters. Shiplap is out. White kitchens are out. Accent walls are out. Then there was an article about how to properly fold plastic grocery bags. I’m not kidding. Did you know you’ve been storing plastic grocery bags the WRONG WAY all these years? How could you be so incompetent? A capitalist culture only survives as long as people buy things, and advertising (and a lot of other media) is about the ways you need to improve, do it right, be better.

Advertising is manufactured distrust. We’re inadequate, but a widget would make us better. We buy, and we discover we still don’t feel good enough, and another ad tells us we need a nidget. So we buy that, but then we see a gidget on sale that will make us even better …

Who benefits most from our lack of trust in ourselves?

I believe information is power. I believe education is power. I believe in science, data, and critical thinking. I trust those things.

Who benefits most from the breakdown of public education, the demonization and gutting of scientific organizations and communities, manufactured misinformation, manufactured disinformation, and “alternative facts?”

Photo by roya ann miller on Unsplash

The Center For Nonviolent Communication says trust is a human need; it’s listed under connection needs. When our needs aren’t met, our health (mental, physical, emotional) suffers. If we are unable to trust we’re wide open to conspiracy theorists, ideologues, authoritarians, and other abusers and manipulators. Predators happily gorge off the results of manufactured distrust.

This is a big, big, problem, because it stands between us and managing things like climate change. Which, depending on who you talk to, isn’t even real because science has been the target of so much manufactured distrust.

One day, sooner rather than later in the Southwest, a switch won’t deliver electricity and a faucet won’t deliver water. Scientists have been talking about consequences of climate change and drought in the area for decades. It was one of the reasons I left my lifelong home in Colorado and came to Maine nearly eight years ago. A combination of manufactured distrust, denial, and the misplaced priority of winning the next election have effectively stopped any kind of collaborative or cooperative problem-solving around water usage throughout the Colorado River watershed, and here we are, on the brink of multi-state disaster that will affect the whole country.

Trust is a choice we make many times a day. Do we trust our families, coworkers, and friends? Do we trust the headlines we read, the news anchor we hear, or the algorithms providing us with “information” on social media? Do we trust what lands in our Inbox or the unfamiliar number calling us? Do we trust the oncoming car will really stop so we can safely walk across the busy street?

More importantly, do we trust our own instincts, feelings, and capability? Do we actively teach our children to trust theirs? Do we encourage our friends and loved ones to trust themselves? Or do we tell people they have it wrong, it didn’t happen, they’re being ridiculous, they don’t understand?

Choice comes with consequences and responsibility. Choice is dynamic; do we trust if we make a choice that doesn’t work out the way we hoped, we’ll choose again? Do we trust ourselves to be wrong and learn something before we choose again? Do we trust our ability to problem solve, bounce back, and do the best we can most of the time?

I suppose somewhere between having no trust at all and trusting everyone and everything lies a fine line of willingness to trust. We could approach new situations and people with curiosity and an open mind, be big enough to give the benefit of the doubt, and have healthy enough boundaries and the self-trust to disengage when we have evidence and experience indicating our trust is misplaced.

The first step in rejecting manufactured distrust is building trust in ourselves and demonstrating our own reliability, truth, ability and strength as we engage with others.

Photo by Ryan Moreno on Unsplash